Modern French Pictures at the National Gallery

MODERN FRENCH PICTURES

AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY.

BY T. MARTIN WOOD

j

THE French Impressionist school will

take rank, I believe, with the greatest

schools of the world. It succeeded

so perfectly in what it set out to do

that painting is already seeking a new direction,

and what it achieved was in a field of experience

which preceding ages had considered to lie

almost beyond the province of artistic expres-

sion. Some day this school will be admitted to

rank with the supreme schools of the Italian

Renaissance—the more readily so from the very

fact that it sought its triumphs in an entirely

different field. Impressionism expresses an age

the most short-lived the world has known, end-

ing with the war that will change for decades,

if not for ever, the atmosphere of everyday life.

At no time, probably, did men live so vividly

as in that swift age—if life is to be measured in

degree of consciousness. There never was art

so responsive as Impressionism; it registered

every faint experience. At its best it is without

a single accent of exaggeration. Life, it would

seem to say, in its quietest aspect is so important

that an art of pure response is sufficient. In

representing life it would add nothing to it.

All that is evanescent, everything that will pass,

not to return in the same shape, must be arrested

and the image of it perpetuated. Of this art

that of Manet, Monet, and Degas is the most

characteristic, the most sure of lasting fame.

It does not aspire to express romantic ideas or

soft emotions, but it is so receptive to sensation

that the world in its most everyday complexion

affords it an inexhaustible theme. Any emotion

which would make it difficult for the artist to

sustain the attitude of pure receptivity was to

be avoided. The painter’s attitude was to be

that of a mystic, and it was certainly that of

one moved to ecstasy by the splendour of the

appearance of the material world. We should

expect, then, in the art that expresses such a

frame of mind, a rare spontaneity and exquisitely

nervous execution. In the painting of no other

school do we find execution of such sensibility.

It is most remarkable of all in Manet, whose

touch refines expression as sensitively as any

painist’s.

No man seems to have loved the material

world in every particle more than Degas. He

is enthusiastic in his art about even the dust

of a floor made visible in limelight. Unlike

Manet’s, Degas’ touch does not transmute.

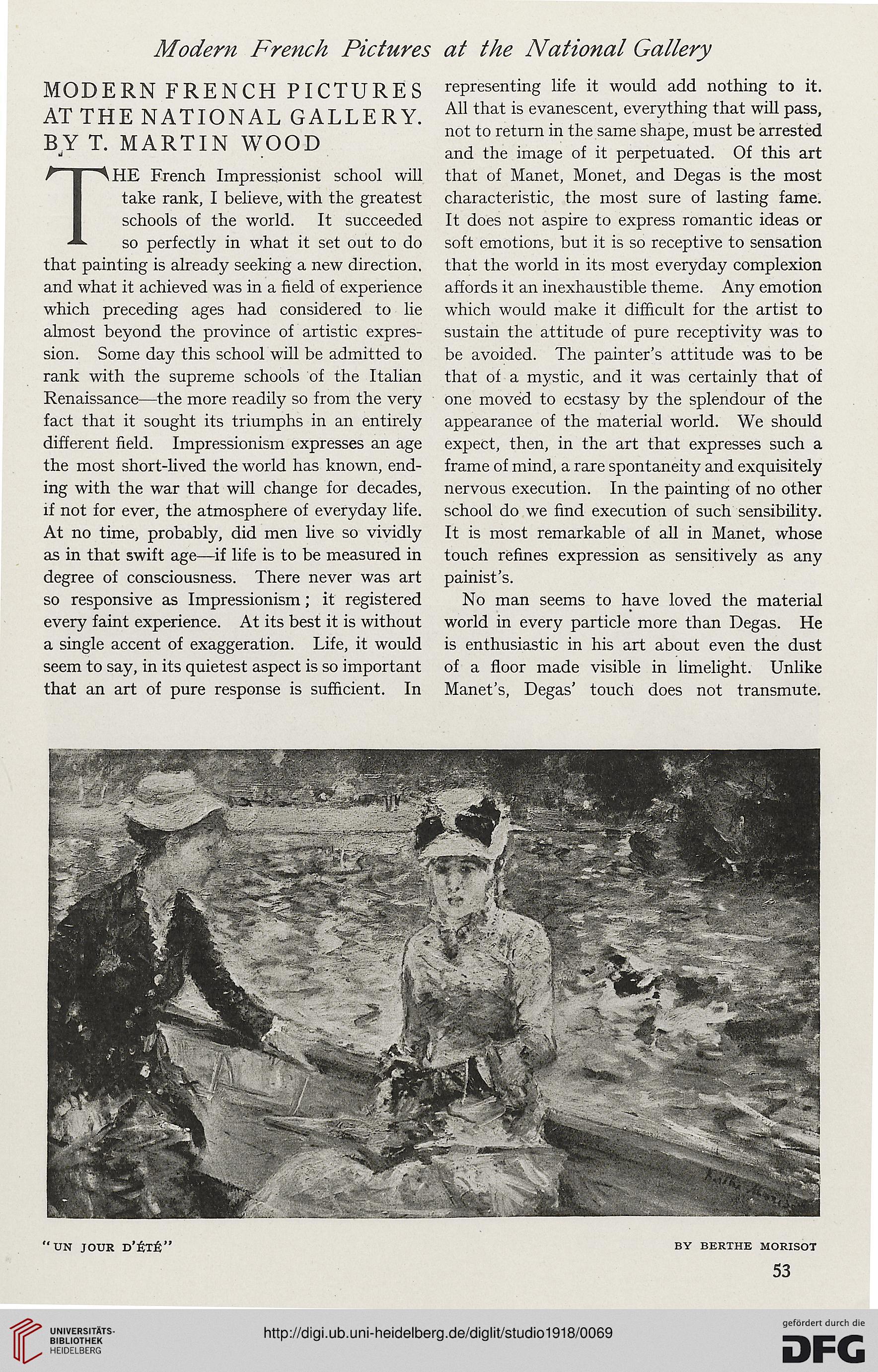

UN JOUR d’£t:6”

MODERN FRENCH PICTURES

AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY.

BY T. MARTIN WOOD

j

THE French Impressionist school will

take rank, I believe, with the greatest

schools of the world. It succeeded

so perfectly in what it set out to do

that painting is already seeking a new direction,

and what it achieved was in a field of experience

which preceding ages had considered to lie

almost beyond the province of artistic expres-

sion. Some day this school will be admitted to

rank with the supreme schools of the Italian

Renaissance—the more readily so from the very

fact that it sought its triumphs in an entirely

different field. Impressionism expresses an age

the most short-lived the world has known, end-

ing with the war that will change for decades,

if not for ever, the atmosphere of everyday life.

At no time, probably, did men live so vividly

as in that swift age—if life is to be measured in

degree of consciousness. There never was art

so responsive as Impressionism; it registered

every faint experience. At its best it is without

a single accent of exaggeration. Life, it would

seem to say, in its quietest aspect is so important

that an art of pure response is sufficient. In

representing life it would add nothing to it.

All that is evanescent, everything that will pass,

not to return in the same shape, must be arrested

and the image of it perpetuated. Of this art

that of Manet, Monet, and Degas is the most

characteristic, the most sure of lasting fame.

It does not aspire to express romantic ideas or

soft emotions, but it is so receptive to sensation

that the world in its most everyday complexion

affords it an inexhaustible theme. Any emotion

which would make it difficult for the artist to

sustain the attitude of pure receptivity was to

be avoided. The painter’s attitude was to be

that of a mystic, and it was certainly that of

one moved to ecstasy by the splendour of the

appearance of the material world. We should

expect, then, in the art that expresses such a

frame of mind, a rare spontaneity and exquisitely

nervous execution. In the painting of no other

school do we find execution of such sensibility.

It is most remarkable of all in Manet, whose

touch refines expression as sensitively as any

painist’s.

No man seems to have loved the material

world in every particle more than Degas. He

is enthusiastic in his art about even the dust

of a floor made visible in limelight. Unlike

Manet’s, Degas’ touch does not transmute.

UN JOUR d’£t:6”