Katia Johansen

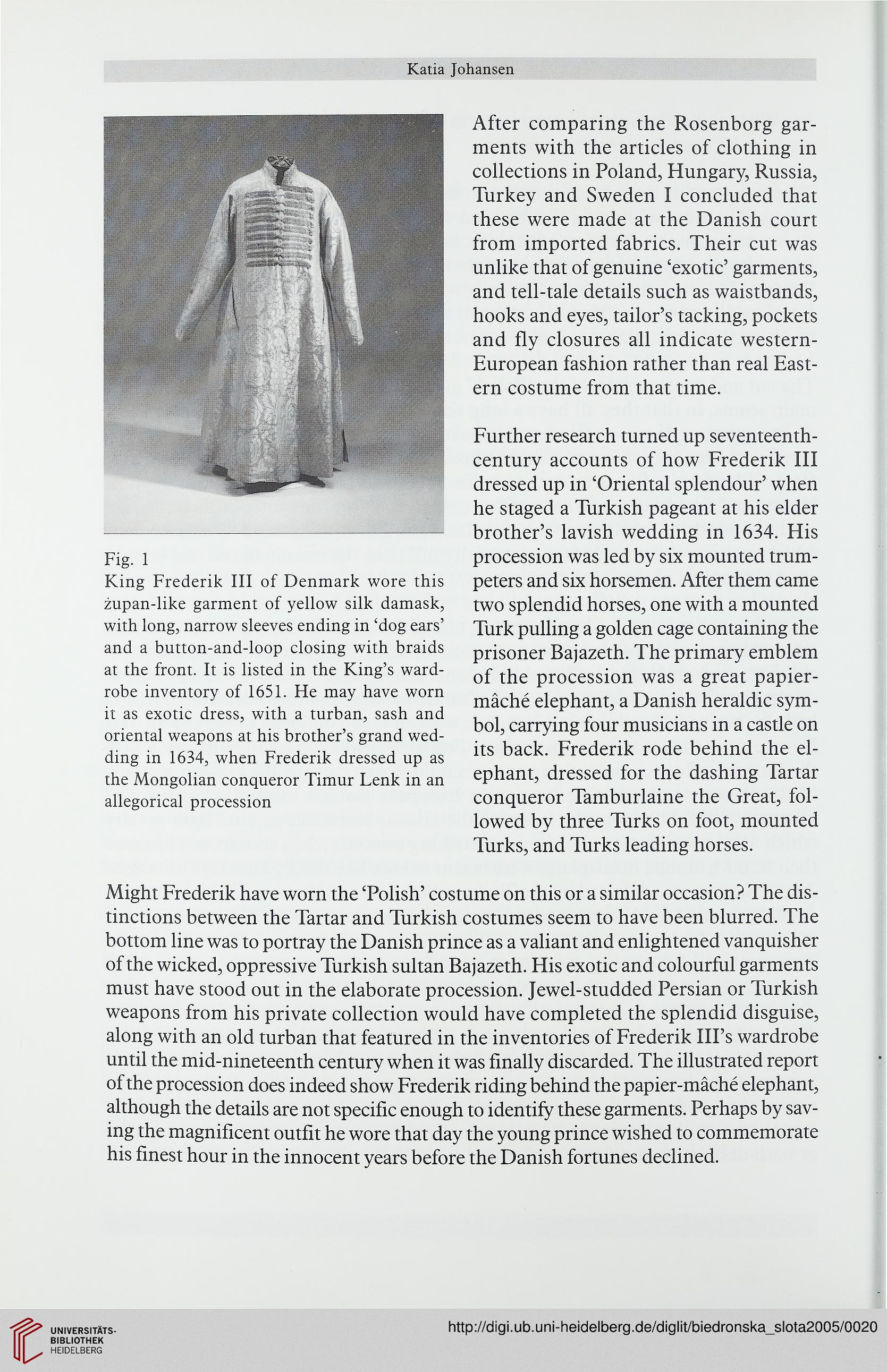

Fig. 1

King Frederik III of Denmark wore this

żupan-like garment of yellow silk damask,

with long, narrow sleeves ending in 'dog ears'

and a button-and-loop closing with braids

at the front. It is listed in the King's ward-

robe inventory of 1651. He may have worn

it as exotic dress, with a turban, sash and

oriental weapons at his brother's grand wed-

ding in 1634, when Frederik dressed up as

the Mongolian conąueror Timur Lenk in an

allegorical procession

After comparing the Rosenborg gar-

ments with the articles of clothing in

collections in Poland, Hungary, Russia,

Turkey and Sweden I concluded that

these were made at the Danish court

from imported fabrics. Their cut was

unlike that of genuine 'exotic' garments,

and tell-tale details such as waistbands,

hooks and eyes, tailor's tacking, pockets

and fly closures all indicate western-

European fashion rather than real East-

ern costume from that time.

Further research turned up seventeenth-

century accounts of how Frederik III

dressed up in 'Oriental splendour' when

he staged a Turkish pageant at his elder

brother's lavish wedding in 1634. His

procession was led by six mounted trum-

peters and six horsemen. After them came

two splendid horses, one with a mounted

Turk pulling a golden cage containing the

prisoner Bajazeth. The primary emblem

of the procession was a great papier-

mache elephant, a Danish heraldic sym-

bol, carrying four musicians in a castle on

its back. Frederik rode behind the el-

ephant, dressed for the dashing Tartar

conąueror Tamburlaine the Great, fol-

lowed by three Turks on foot, mounted

Turks, and Turks leading horses.

Might Frederik have worn the 'Polish' costume on this or a similar occasion? The dis-

tinctions between the Tartar and Turkish costumes seem to have been blurred. The

bottom line was to portray the Danish prince as a valiant and enlightened vanquisher

of the wicked, oppressive Turkish sułtan Bajazeth. His exotic and colourful garments

must have stood out in the elaborate procession. Jewel-studded Persian or Turkish

weapons from his private collection would have completed the splendid disguise,

along with an old turban that featured in the inventories of Frederik III's wardrobe

until the mid-nineteenth century when it was finally discarded. The illustrated report

of the procession does indeed show Frederik riding behind the papier-mache elephant,

although the details are not specific enough to identify these garments. Perhaps by sav-

ing the magnificent outfit he wore that day the young prince wished to commemorate

his finest hour in the innocent years before the Danish fortunes declined.

Fig. 1

King Frederik III of Denmark wore this

żupan-like garment of yellow silk damask,

with long, narrow sleeves ending in 'dog ears'

and a button-and-loop closing with braids

at the front. It is listed in the King's ward-

robe inventory of 1651. He may have worn

it as exotic dress, with a turban, sash and

oriental weapons at his brother's grand wed-

ding in 1634, when Frederik dressed up as

the Mongolian conąueror Timur Lenk in an

allegorical procession

After comparing the Rosenborg gar-

ments with the articles of clothing in

collections in Poland, Hungary, Russia,

Turkey and Sweden I concluded that

these were made at the Danish court

from imported fabrics. Their cut was

unlike that of genuine 'exotic' garments,

and tell-tale details such as waistbands,

hooks and eyes, tailor's tacking, pockets

and fly closures all indicate western-

European fashion rather than real East-

ern costume from that time.

Further research turned up seventeenth-

century accounts of how Frederik III

dressed up in 'Oriental splendour' when

he staged a Turkish pageant at his elder

brother's lavish wedding in 1634. His

procession was led by six mounted trum-

peters and six horsemen. After them came

two splendid horses, one with a mounted

Turk pulling a golden cage containing the

prisoner Bajazeth. The primary emblem

of the procession was a great papier-

mache elephant, a Danish heraldic sym-

bol, carrying four musicians in a castle on

its back. Frederik rode behind the el-

ephant, dressed for the dashing Tartar

conąueror Tamburlaine the Great, fol-

lowed by three Turks on foot, mounted

Turks, and Turks leading horses.

Might Frederik have worn the 'Polish' costume on this or a similar occasion? The dis-

tinctions between the Tartar and Turkish costumes seem to have been blurred. The

bottom line was to portray the Danish prince as a valiant and enlightened vanquisher

of the wicked, oppressive Turkish sułtan Bajazeth. His exotic and colourful garments

must have stood out in the elaborate procession. Jewel-studded Persian or Turkish

weapons from his private collection would have completed the splendid disguise,

along with an old turban that featured in the inventories of Frederik III's wardrobe

until the mid-nineteenth century when it was finally discarded. The illustrated report

of the procession does indeed show Frederik riding behind the papier-mache elephant,

although the details are not specific enough to identify these garments. Perhaps by sav-

ing the magnificent outfit he wore that day the young prince wished to commemorate

his finest hour in the innocent years before the Danish fortunes declined.