Painted representations of drunkermess ard gluttony were most often closely linked with the

rcality of the period46. In his report of 1674, entitkd Observalicns upon the United Provinces

of the Netherlands, ambassador William Tempie wrote that liąuor Was the only joy in the life

of these people and „that, for all their tme liches they would seem poor ard unhappy without

it"47. The feasts ard drinking bouts organized by the Butch obeyed specific icgulations, for

instance, the number of toasts raiftd was equal to the number of guests, or the big glasscs had

the shape of beakers or fhites. The host considercd himself a simpleton if he d'd not prime his

guests with liquor, neither did he trust those who drank less than himself. Quite improbable

quantities of focd were devoured.

The tradition of gluttony and drunkenness must have bcen deeply rooted in Germany and

the Netherlands sińce its allegoric representations in painting date back to the 15th century

and occur in mimerous paintings by Hieronymus Bosch who, in addition to stupidity, dedicated

much of his attention to this problem (Allegory of Dipsomania and Gluttony, The Oyster-Shell

or Seven Deadly Sins). Likewise, the central part of the tiiptych The Temptaiion of St. Anthony

46. Cf. P. Zumthor, La vie ąuoiidienne en Hollande au temps de Rembrandt, Paris, 1959, pp. 156—160; Tot Leering en Vcrmauk.

Betekenissen van Holłandse genreroorslellingen uit de zeventiende eenw. Catalogus, Rijksmuscuni Amsterdam, 16 scptcmber

to 5 december 1976, p. 248.

47. P. Zumthor, op. cii.,

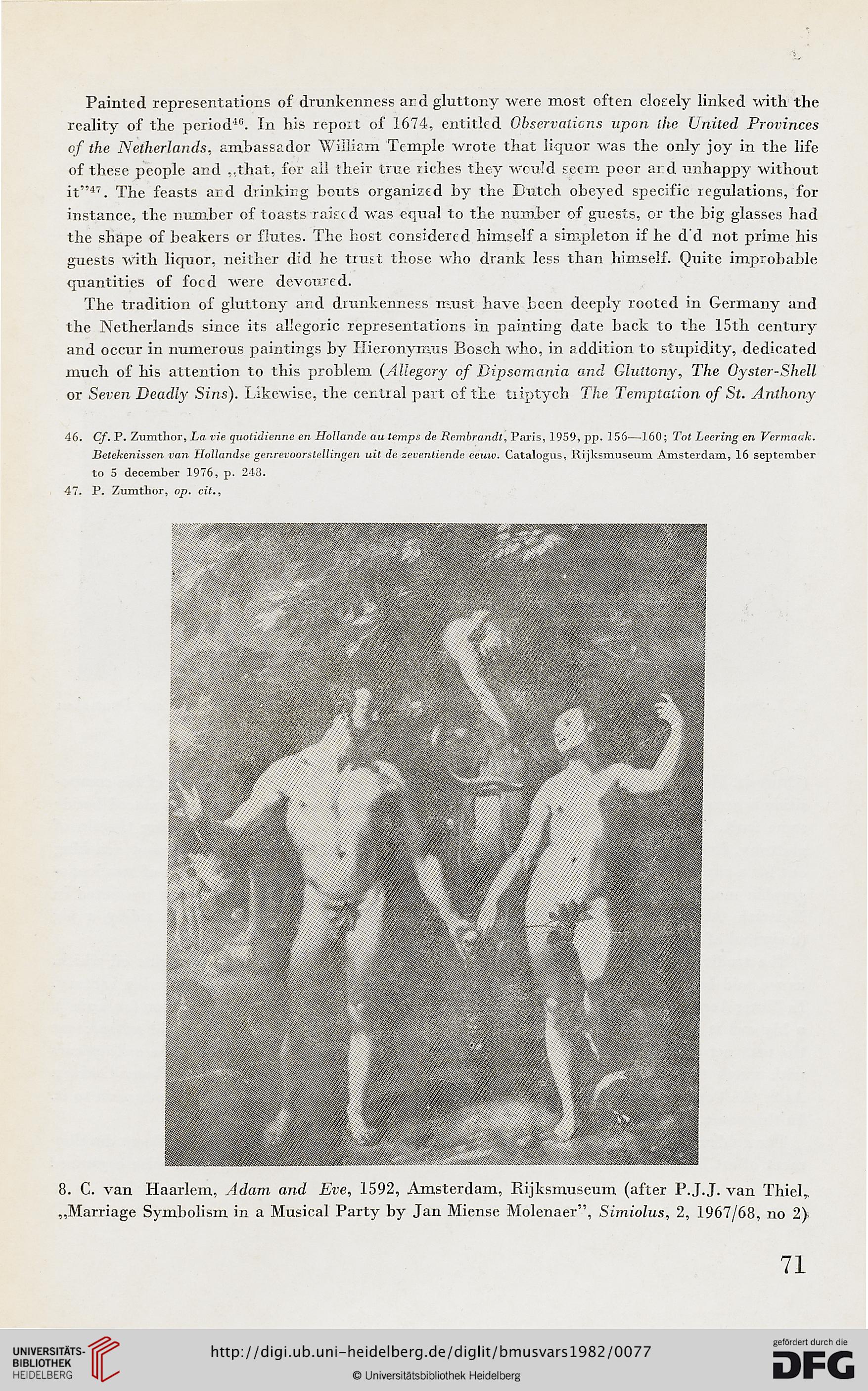

3. C. van Haarlcm, Adam and Eve, 1592, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (after P.J.J. van Thiela

„Marriage Symbolism in a Musical Party by Jan Miense Molenaer", Simiolus, 2, 1967/68, no 2)

71

rcality of the period46. In his report of 1674, entitkd Observalicns upon the United Provinces

of the Netherlands, ambassador William Tempie wrote that liąuor Was the only joy in the life

of these people and „that, for all their tme liches they would seem poor ard unhappy without

it"47. The feasts ard drinking bouts organized by the Butch obeyed specific icgulations, for

instance, the number of toasts raiftd was equal to the number of guests, or the big glasscs had

the shape of beakers or fhites. The host considercd himself a simpleton if he d'd not prime his

guests with liquor, neither did he trust those who drank less than himself. Quite improbable

quantities of focd were devoured.

The tradition of gluttony and drunkenness must have bcen deeply rooted in Germany and

the Netherlands sińce its allegoric representations in painting date back to the 15th century

and occur in mimerous paintings by Hieronymus Bosch who, in addition to stupidity, dedicated

much of his attention to this problem (Allegory of Dipsomania and Gluttony, The Oyster-Shell

or Seven Deadly Sins). Likewise, the central part of the tiiptych The Temptaiion of St. Anthony

46. Cf. P. Zumthor, La vie ąuoiidienne en Hollande au temps de Rembrandt, Paris, 1959, pp. 156—160; Tot Leering en Vcrmauk.

Betekenissen van Holłandse genreroorslellingen uit de zeventiende eenw. Catalogus, Rijksmuscuni Amsterdam, 16 scptcmber

to 5 december 1976, p. 248.

47. P. Zumthor, op. cii.,

3. C. van Haarlcm, Adam and Eve, 1592, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (after P.J.J. van Thiela

„Marriage Symbolism in a Musical Party by Jan Miense Molenaer", Simiolus, 2, 1967/68, no 2)

71