THE SOURCES — THE NAME

19

elements. The other sources, if there be more than one, cannot be separately dis-

tinguished now; they are apparent in those features which cannot be recognized as

of Greco-Roman origin, and which, for the sake of clearness, will be called the native

elements.

The classic elements will speak for themselves ; they are easily recognized. I have

referred to their sources as Greco-Roman and not simply Roman, because the ele-

ments, as they appear, although they were introduced into Northern Syria in impe-

rial Roman times, are those of Grecian origin. The native elements are less familiar

and should be briefly described. The most conspicuous feature that is foreign to the

classic styles is the use of enormous blocks of stone in buildings

of all kinds. This form of construction is as old in Syria as the

foundations of the Temple of the Sun at Ba'albek, though, of

course, it is practised on a smaller scale in the buildings now

under discussion. This style of building we shall call mega-

lithic construction. In the same connection may be mentioned

the employment of great slabs of stone for intermediate floors

and for roofs of short span, which seems an anomaly in a country

where wood must have been very plentiful, judging from its lav-

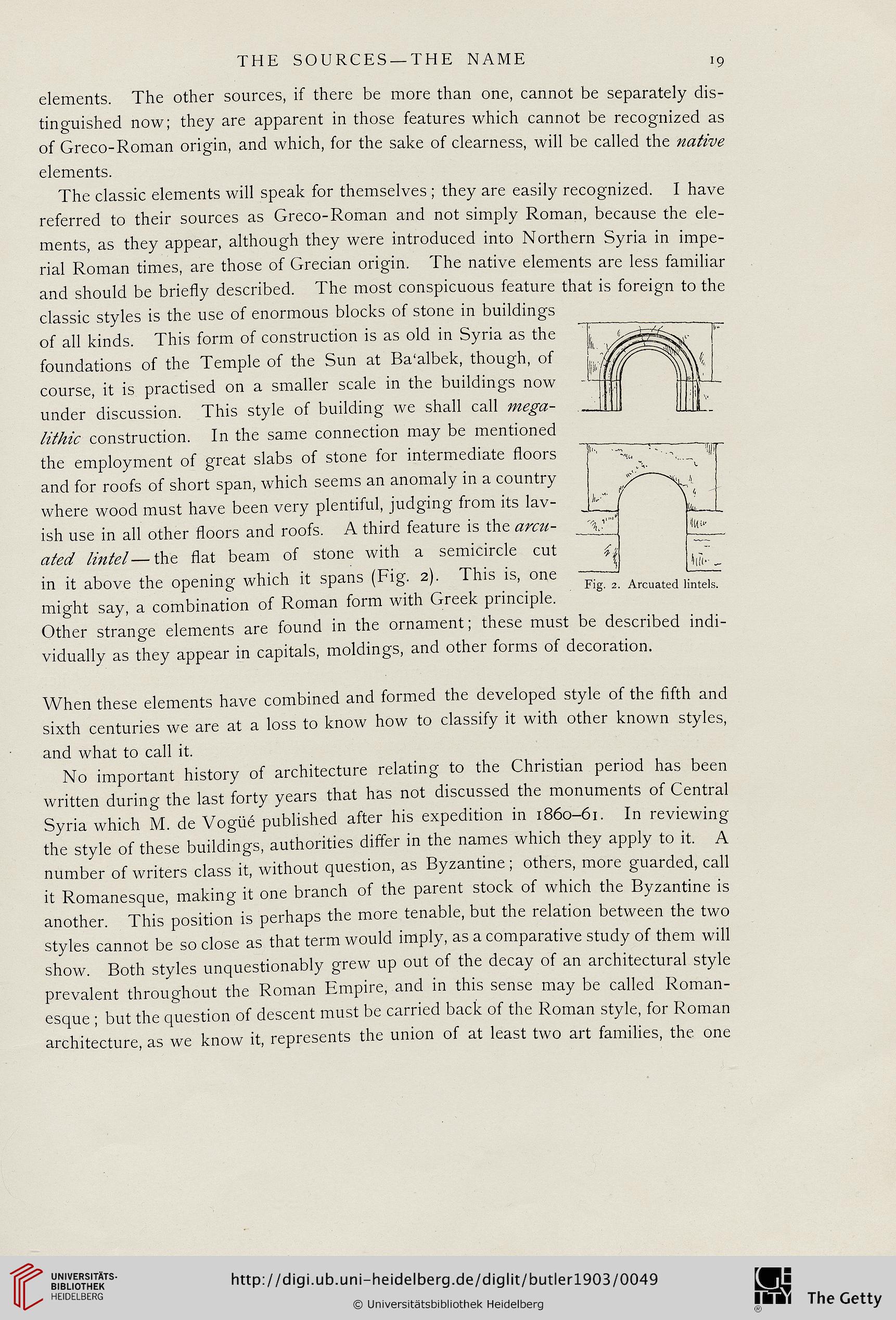

ish use in all other floors and roofs. A thircl feature is the arcu-

ated lintel— the flat beam of stone with a semicircle cut

in it above the opening which it spans (Fig. 2). This is, one

might say, a combination of Roman form with Greek principle.

Other strange elements are found in the ornament; these must be described indi-

vidually as they appear in capitals, moldings, and other forms of decoration.

h

¥

c

—w

h

iA

f 1

(,

. v

'X'

iKii-

S "

Fig. 2. Arcuated lintels.

When these elements have combined and formed the developed style of the fifth and

sixth centuries we are at a loss to know how to classify it with other known styles,

and what to call it.

No important history of architecture relating to the Christian period has been

written during the last forty years that has not discussed the monuments of Central

Syria which M. de Vogiie published after his expedition in 1860-61. In reviewing

the style of these buildings, authorities differ in the names which they apply to it. A

number of writers class it, without question, as Byzantine ; others, more guarded, call

it Romanesque, making it one branch of the parent stock of which the Byzantine is

another. This position is perhaps the more tenable, but the relation between the two

styles cannot be so close as that term would imply, as a comparative study of them will

show. Both styles unquestionably grew up out of the decay of an architectural style

prevalent throughout the Roman Empire, and in this sense may be called Roman-

esque ; but the question of descent must be carried back of the Roman style, for Roman

architecture, as we know it, represents the union of at least two art families, the one

19

elements. The other sources, if there be more than one, cannot be separately dis-

tinguished now; they are apparent in those features which cannot be recognized as

of Greco-Roman origin, and which, for the sake of clearness, will be called the native

elements.

The classic elements will speak for themselves ; they are easily recognized. I have

referred to their sources as Greco-Roman and not simply Roman, because the ele-

ments, as they appear, although they were introduced into Northern Syria in impe-

rial Roman times, are those of Grecian origin. The native elements are less familiar

and should be briefly described. The most conspicuous feature that is foreign to the

classic styles is the use of enormous blocks of stone in buildings

of all kinds. This form of construction is as old in Syria as the

foundations of the Temple of the Sun at Ba'albek, though, of

course, it is practised on a smaller scale in the buildings now

under discussion. This style of building we shall call mega-

lithic construction. In the same connection may be mentioned

the employment of great slabs of stone for intermediate floors

and for roofs of short span, which seems an anomaly in a country

where wood must have been very plentiful, judging from its lav-

ish use in all other floors and roofs. A thircl feature is the arcu-

ated lintel— the flat beam of stone with a semicircle cut

in it above the opening which it spans (Fig. 2). This is, one

might say, a combination of Roman form with Greek principle.

Other strange elements are found in the ornament; these must be described indi-

vidually as they appear in capitals, moldings, and other forms of decoration.

h

¥

c

—w

h

iA

f 1

(,

. v

'X'

iKii-

S "

Fig. 2. Arcuated lintels.

When these elements have combined and formed the developed style of the fifth and

sixth centuries we are at a loss to know how to classify it with other known styles,

and what to call it.

No important history of architecture relating to the Christian period has been

written during the last forty years that has not discussed the monuments of Central

Syria which M. de Vogiie published after his expedition in 1860-61. In reviewing

the style of these buildings, authorities differ in the names which they apply to it. A

number of writers class it, without question, as Byzantine ; others, more guarded, call

it Romanesque, making it one branch of the parent stock of which the Byzantine is

another. This position is perhaps the more tenable, but the relation between the two

styles cannot be so close as that term would imply, as a comparative study of them will

show. Both styles unquestionably grew up out of the decay of an architectural style

prevalent throughout the Roman Empire, and in this sense may be called Roman-

esque ; but the question of descent must be carried back of the Roman style, for Roman

architecture, as we know it, represents the union of at least two art families, the one