////// .$7/7/-/,?)/?

that " parerga," or side-works of this description,

are often of exceptional interest, having an intimacy

about them that is peculiariy attractive. It is with

art, that is to say, as it is with nature. The iarge,

main, obviousiy important characteristics of a

country do not exhaust it for us ; and when these

have become famiiiar, have impressed themselves

upon us, it is more than possible that by happy

accident we may come across some retired quarter

of it where unsuspected delights lurk and capture

our attention. These nooks and by-ways may

undoubtedly gain something even from the mere

fact of their retirement. They are not everybody's

property who travels there ; but, apart from this,

they often contain certain beauties and surprises

of their own which are singularly attractive.

This is so with nature. And instances will arise to

every reader's mind in which something analogous

occurs in the life and work of innumerable artists

in every form of the arts. As Browning somewhere

says, What would one not give to read a poem by

Raphael, to see a painting by Dante ! What a

curious delight it is to come upon a man of real

character doing something purely for his own

satisfaction—not the thing expected of him, but a

thing he has been moved to do at the moment for

his own enjoyment, though it should bring no name

or reward along with it!

For the purpose in hand let me here make

another general remark, not, I think, irrelevant.

In every department of

art there are many ways, it

must be remembered, of

producing admirable results

—results as dissimilar from

one another as have been

the tastes and aims of the

artists essaying them. Of

this we have often to remind

ourselves when criticising

or looking at works which

do not at once commend

themselves to us ; although,

of course, in so many words

no one questions the fact,

except when he is very

young, or is in a temper, or

is anxious to set somebody

by the ears. Let us take

the art of painting still-Iife,

or to iimit ourselves yet

closer—the art of painting

fruit and flowers. In the

days of our forefathers it

was van Huysum's fruit

and ftower pieces that were

held up to superlative ad-

miration ; while in the days

of Ruskin's ascendency it

was the fruit and Hower

pieces of our own country-

man, William Hunt. Now,

though these men's subjects

were the same, it would be

difHcult to hnd two methods

of observation and treat-

ment more unlike. Both

van Huysum and William

Hunt are somewhat out of

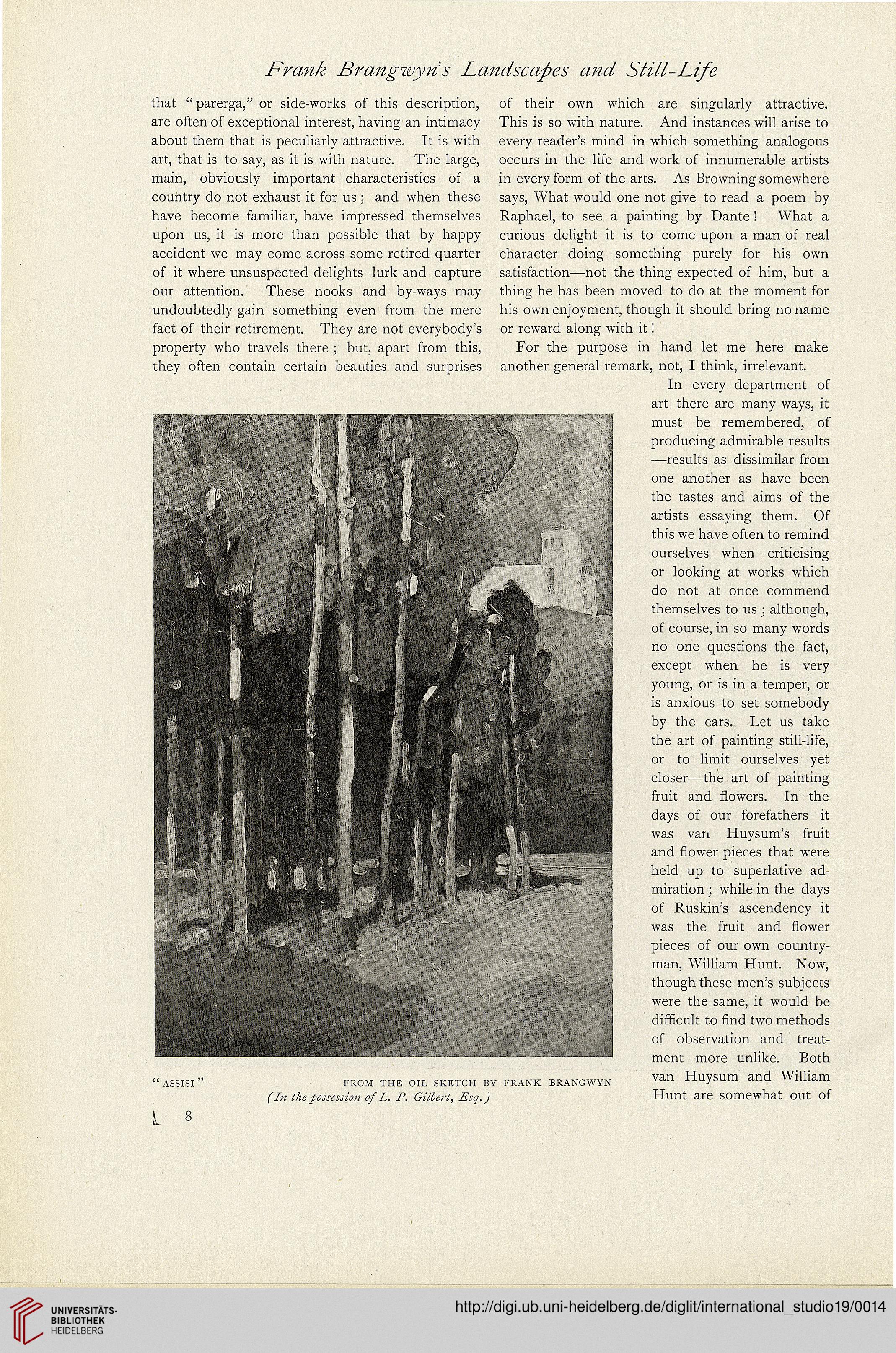

" ASSISI'

FROM THE OIL SKETCH BY FRANK BRANGWYN