when his modelling is heavy and lumpy, but this

defect of inexperience wiil pass away, and the

assured strength will remain. In one group,

there is some disunion between the

hgures, for while the blind girl herself is in

repose, the boy against whom she leans walks

forward. This troubles the whole purpose of the

design and weakens the effect of the truthful and

rugged pathos. But if Mr. Wells invites criticism

here and there, he is none the less a true artist and

a gifted young sculptor. His statuettes never

seem too small or too large; his feeling for scale

and for weight of style has an impressive originality,

and his subjects are already varied in their range

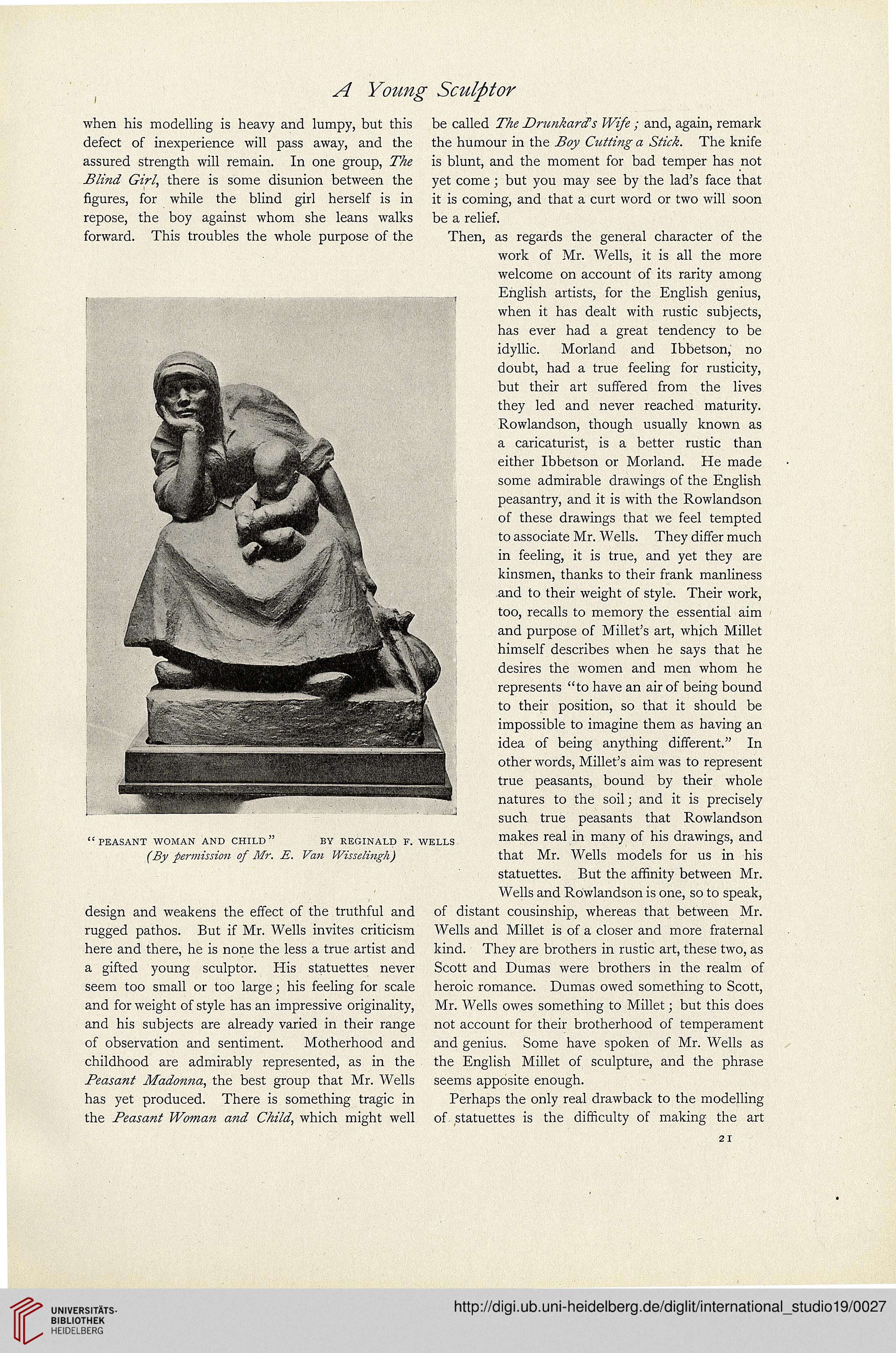

of observation and sentiment. Motherhood and

childhood are admirably represented, as in the

A<2.M72/ the best group that Mr. Wells

has yet produced. There is something tragic in

the A<2.M72/ fn?77M73 <2726? which might well

be called Z>7'?2/2/&<27V.f IF2/9 ; and, again, remark

the humour in the Ci/iY/Ti.g'a &*2<rA The knife

is blunt, and the moment for bad temper has not

yet come ; but you may see by the lad's face that

it is coming, and that a curt word or two will soon

be a relief.

Then, as regards the general character of the

work of Mr. Wells, it is all the more

welcome on account of its rarity among

English artists, for the English genius,

when it has dealt with rustic subjects,

has ever had a great tendency to be

idyllic. Morland and Ibbetson, no

doubt, had a true feeling for rusticity,

but their art suffered from the lives

they led and never reached maturity.

Rowlandson, though usually known as

a caricaturist, is a better rustic than

either Ibbetson or Morland. He made

some admirable drawings of the English

peasantry, and it is with the Rowlandson

of these drawings that we feel tempted

to associate Mr. Wells. They differ much

in feeling, it is true, and yet they are

kinsmen, thanks to their frank manliness

and to their weight of style. Their work,

too, recalls to memory the essential aim

and purpose of Millet's art, which Millet

himself describes when he says that he

desires the women and men whom he

represents "to have an air of being bound

to their position, so that it should be

impossible to imagine them as having an

idea of being anything different." In

other words, Millet's aim was to represent

true peasants, bound by their whole

natures to the soil; and it is precisely

such true peasants that Rowlandson

makes real in many of his drawings, and

that Mr. Wells models for us in his

statuettes. But the afEnity between Mr.

Wells and Rowlandson is one, so to speak,

of distant cousinship, whereas that between Mr.

Wells and Millet is of a closer and more fraternal

kind. They are brothers in rustic art, these two, as

Scott and Dumas were brothers in the realm of

heroic romance. Dumas owed something to Scott,

Mr. Wells owes something to Millet; but this does

not account for their brotherhood of temperament

and genius. Some have spoken of Mr. Wells as

the English Millet of sculpture, and the phrase

seems apposite enough.

Perhaps the only real drawback to the modelling

of statuettes is the difhculty of making the art

"PEASANT WOMAN AND CHILD" BY REGINALD F. WELLS

f^<//'////JJ/</// <^f 7l<//'. W %Z72 ^2^/272^ j

21