for alert and vigorously expressive movement was a

legacy thatjean Goujon (igig?—1572) inherited

from his forerunners, the Gothic stonemasons and

carvers; and if you study the work of Goujon's

successors, from the time of Germain Pilon to

those of Barye and Carpeaux, you will hnd that

the same fondness iived on as a tradition, till at

last it became a potent induence in the life and

work of Auguste Rodin. Then, iittie by little, it

was transformed beyond recognition in a wonderful,

unique manner, for Rodin blent it with an energy

more naturalistic, and with a passion more vehement

and more sexual, than had ever appeared before in

the art of sculpture.

In truth, the genius and the work of Rodin

mark an epoch in history. They represent a

nation and a type of society, they belong to France

and the nineteenth century. By them we are in-

troduced to a modern Michael Angelo that pro-

vokes discussion instead of awe, so responsive is

he to the scientific tendencies of the age he lives

in, and so moved by those emotions of a sexual

kind to which the French give so much attention,

in literature and in art. Most critics are diffident

when they stand in the presence of Buonarotti,

that great and lonely monarch among the leaders

of genius; they stand aloof, and are content to be

silent courtiers. But when they begin to study the

kindred greatness of Rodin, they feel at once that

Buonarotti's kingliness and authority have de-

scended from their throne and become democratic.

The spirit of the modern world has triumphed,

giving us a Michael Angelo of its own breeding

and rearing.

This.' is why friends and foes alike have treated

the genius of Rodin with a familiarity such as

popular newspapers show to the

leading statesmen of the hour.

Insults, impertinent Hatteries,

silly dithyrambs, endless gabble

and endless gush—all these

things Auguste Rodin must

know a great deal too well;

and it is to be remarked also

that his admirers, like his de-

tractors, are generally far more

eager to examine his great work

bit by bit, than to see it as

a whole, largely and in focus.

Most of them, instead of keeping

closely to essentials, either lose

themselves in the dreary wastes

of metaphysics, or else fHI their

pageswith tiresome descriptions;

and hence it is worth while to

draw attention to those charac-

teristics which M. Rodin him-

self values most highly.

Movement and vitality — a

vitality alive with drama—must

be mentioned first of all, for the

sculptor is not greatly fascinated

by the human body in repose.

Indeed, he is never tired of

reminding us in his work that

the beauty of the human body

is perfected and completed by

the thrill of strong emotions;

hence the deference he pays to

the mute eloquence of gesture,

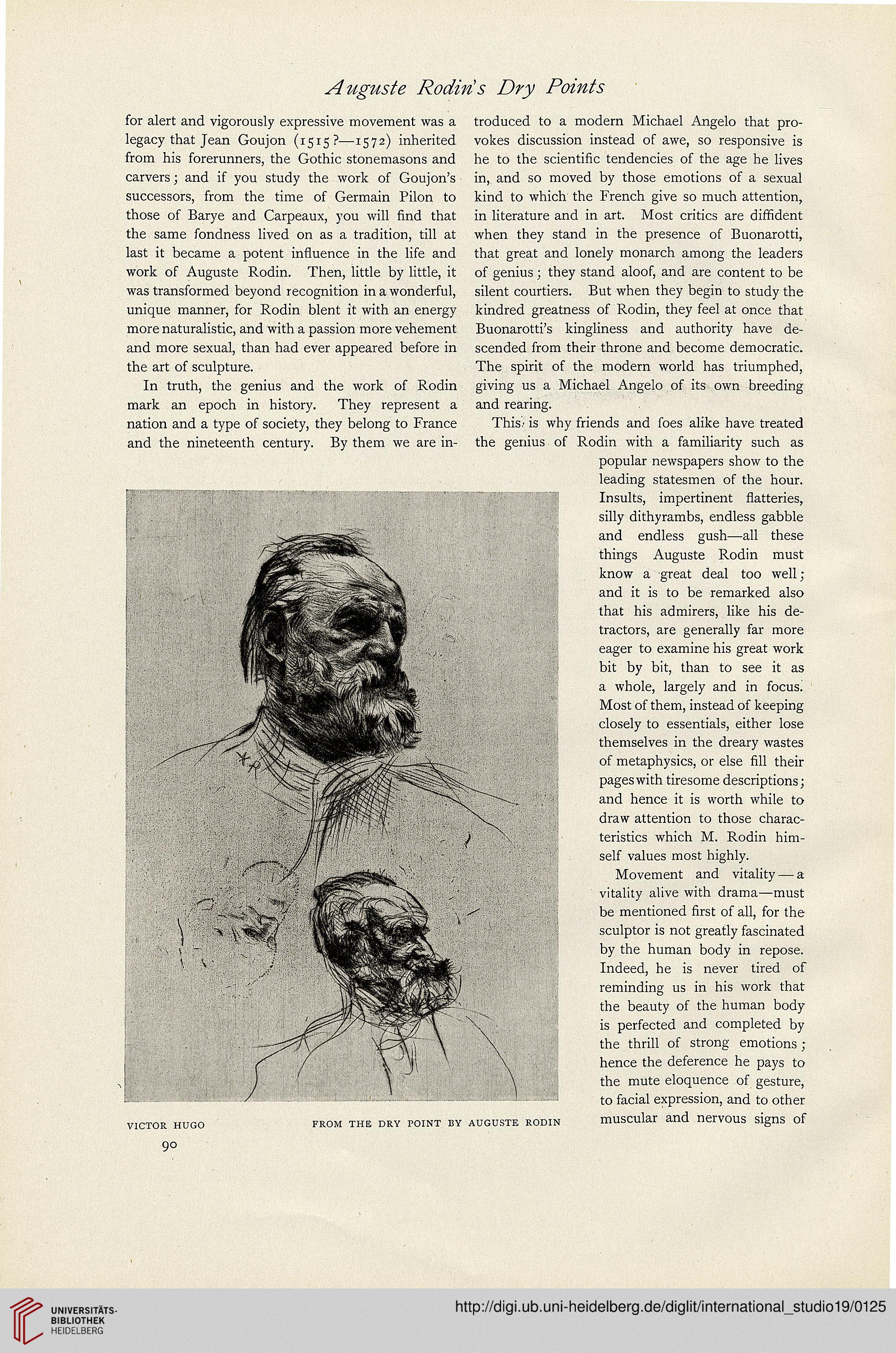

to facial expression, and to other

muscular and nervous signs of