of his day with two new processes, by means of one

or the other of which were produced all the examples

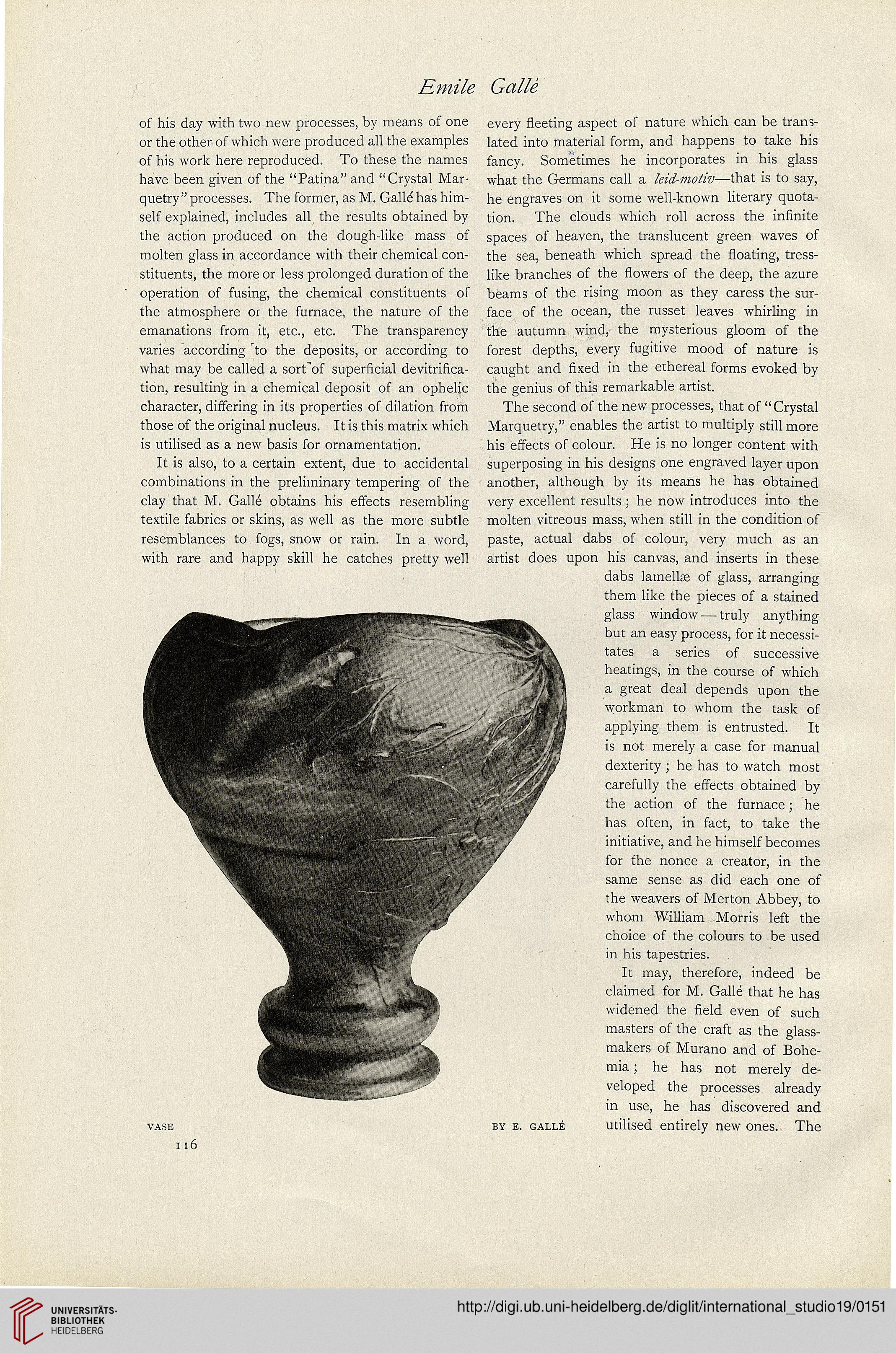

of his work here reproduced. To these the names

have been given of the "Patina" and "Crystal Mar-

quetry " processes. The former, as M. Galld has him-

self explained, includes all the results obtained by

the action produced on the dough-like mass of

tnoiten glass in accordance with their chemical con-

stituents, the more or less prolonged duration of the

operation of fusing, the chemical constituents of

the atmosphere ot the furnace, the nature of the

emanations from it, etc., etc. The transparency

varies according ho the deposits, or according to

what may be calied a sort'of superhcial devitrihca-

tion, resultinjg in a chemical deposit of an ophelic

character, differing in its properties of dilation from

those of the original nucleus. It is this matrix which

is utiiised as a new basis for ornamentation.

It is also, to a certain extent, due to accidentai

combinations in the preliminary tempering of the

clay that M. Galle obtains his effects resembling

textile fabrics or skins, as well as the more subtle

resemblances to fogs, snow or rain. In a word,

with rare and happy skill he catches pretty well

every Heeting aspect of nature which can be trans-

lated into material form, and happens to take his

fancy. Sometimes he incorporates in his glass

what the Germans call a —that is to say,

he engraves on it some well-known literary quota-

tion. The clouds which roll across the inHnite

spaces of heaven, the translucent green waves of

the sea, beneath which spread the Hoating, tress-

like branches of the Howers of the deep, the azure

beams of the rising moon as they caress the sur-

face of the ocean, the russet leaves whirling in

the autumn wind, the mysterious gloom of the

forest depths, every fugitive mood of nature is

caught and hxed in the ethereal forms evoked by

the genius of this remarkable artist.

The second of the new processes, that of "Crystal

Marquetry," enables the artist to multiply still more

his effects of colour. He is no longer content with

superposing in his designs one engraved layer upon

another, although by its means he has obtained

very excellent results; he now introduces into the

molten vitreous mass, when still in the condition of

paste, actual dabs of colour, very much as an

artist does upon his canvas, and inserts in these

dabs lamellte of glass, arranging

them like the pieces of a stained

glass window — truly anything

but an easy process, for it necessi-

tates a series of successive

heatings, in the course of which

a great deal depends upon the

workman to whom the task of

applying them is entrusted. It

is not merely a case for manual

dexterity; he has to watch most

carefully the effects obtained by

the action of the furnace; he

has often, in fact, to take the

initiative, and he himself becomes

for the nonce a creator, in the

same sense as did each one of

the weavers of Merton Abbey, to

whont William Morris left the

choice of the colours to be used

in his tapestries.

It may, therefore, indeed be

claimed for M. Galle that he has

widened the field even of such

masters of the craft as the glass-

makers of Murano and of Bohe-

mia; he has not merely de-

veloped the processes already

in use, he has discovered and

utilised entirely new ones. The