The Tonal School

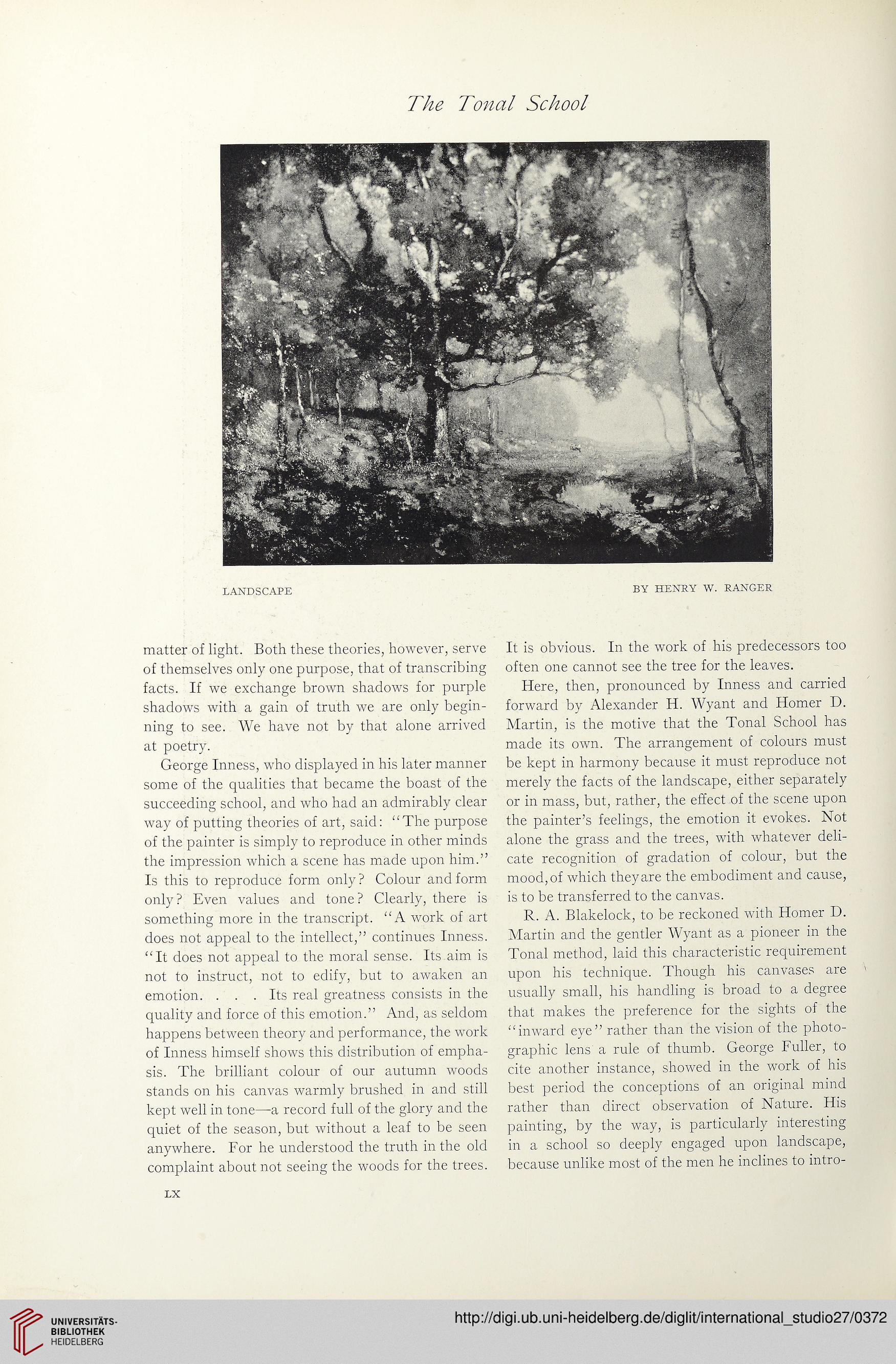

LANDSCAPE

BY HENRY W. RANGER

matter of light. Both these theories, however, serve

of themselves only one purpose, that of transcribing

facts. If we exchange brown shadows for purple

shadows with a gain of truth we are only begin-

ning to see. We have not by that alone arrived

at poetry.

George Inness, who displayed in his later manner

some of the qualities that became the boast of the

succeeding school, and who had an admirably clear

way of putting theories of art, said: “The purpose

of the painter is simply to reproduce in other minds

the impression which a scene has made upon him.”

Is this to reproduce form only ? Colour and form

only? Even values and tone? Clearly, there is

something more in the transcript. “A work of art

does not appeal to the intellect,” continues Inness.

“It does not appeal to the moral sense. Its.aim is

not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an

emotion. . . . Its real greatness consists in the

quality and force of this emotion.” And, as seldom

happens between theory and performance, the work

of Inness himself shows this distribution of ernpha-

sis. The brilliant colour of our autumn woocls

Stands on his canvas warmly brushed in and still

kept well in tone—a record full of the glory and the

quiet of the season, but without a leaf to be seen

anywhere. For he understood the truth in the old

complaint about not seeing the woods for the trees.

LX

It is obvious. In the work of his predecessors too

offen one cannot see the tree for the leaves.

Here, then, pronounced by Inness and carried

forward by Alexander H. Wyant and Homer D.

Martin, is the motive that the Tonal School has

made its own. The arrangement of colours must

be kept in harmony because it must reproduce not

merely the facts of the landscape, either separately

or in mass, but, rather, the effect of the scene upon

the painter’s feelings, the emotion it evokes. Not

alone the grass and the trees, with whatever deli-

cate recognition of gradation of colour, but the

mood,of which theyare the embodiment and cause,

is to be transferred to the canvas.

R. A. Blakelock, to be reckoned with Homer D.

Martin and the gentler Wyant as a pioneer in the

Tonal method, laid this characteristic requirement

upon his technique. Though his canvases are

usually small, his handling is broad to a degree

that makes the preference for the sights of the

“inward eye” rather than the vision of the photo-

graphic lens a rule of thumb. George Füller, to

eite another instance, showed in the work of his

best period the conceptions of an original mind

rather than direct observation of Nature. His

painting, by the way, is particularly interesting

in a school so deeply engaged upon landscape,

because unlike most of the men he inclines to intro-

LANDSCAPE

BY HENRY W. RANGER

matter of light. Both these theories, however, serve

of themselves only one purpose, that of transcribing

facts. If we exchange brown shadows for purple

shadows with a gain of truth we are only begin-

ning to see. We have not by that alone arrived

at poetry.

George Inness, who displayed in his later manner

some of the qualities that became the boast of the

succeeding school, and who had an admirably clear

way of putting theories of art, said: “The purpose

of the painter is simply to reproduce in other minds

the impression which a scene has made upon him.”

Is this to reproduce form only ? Colour and form

only? Even values and tone? Clearly, there is

something more in the transcript. “A work of art

does not appeal to the intellect,” continues Inness.

“It does not appeal to the moral sense. Its.aim is

not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an

emotion. . . . Its real greatness consists in the

quality and force of this emotion.” And, as seldom

happens between theory and performance, the work

of Inness himself shows this distribution of ernpha-

sis. The brilliant colour of our autumn woocls

Stands on his canvas warmly brushed in and still

kept well in tone—a record full of the glory and the

quiet of the season, but without a leaf to be seen

anywhere. For he understood the truth in the old

complaint about not seeing the woods for the trees.

LX

It is obvious. In the work of his predecessors too

offen one cannot see the tree for the leaves.

Here, then, pronounced by Inness and carried

forward by Alexander H. Wyant and Homer D.

Martin, is the motive that the Tonal School has

made its own. The arrangement of colours must

be kept in harmony because it must reproduce not

merely the facts of the landscape, either separately

or in mass, but, rather, the effect of the scene upon

the painter’s feelings, the emotion it evokes. Not

alone the grass and the trees, with whatever deli-

cate recognition of gradation of colour, but the

mood,of which theyare the embodiment and cause,

is to be transferred to the canvas.

R. A. Blakelock, to be reckoned with Homer D.

Martin and the gentler Wyant as a pioneer in the

Tonal method, laid this characteristic requirement

upon his technique. Though his canvases are

usually small, his handling is broad to a degree

that makes the preference for the sights of the

“inward eye” rather than the vision of the photo-

graphic lens a rule of thumb. George Füller, to

eite another instance, showed in the work of his

best period the conceptions of an original mind

rather than direct observation of Nature. His

painting, by the way, is particularly interesting

in a school so deeply engaged upon landscape,

because unlike most of the men he inclines to intro-