Anton Mauve

to read into a pi nting ideas which the painter

never conceived or recorded. Who cannot picture

the bewildered astonishment of Leonardo when

Pater in Elysium reads him his too eloquent

appreciation of La Gioconda ? Mauve’s art is

serious, pensive if you like, but pensiveness is

not necessarily melancholy or sadness. It may

be a deep, though quiet, abiding joy. Sadness or

melancholy implies discontent, if resigned; but the

Titanic element is almost wholly absent in Mauve,

and the greater number of his reveries seem to me

inspired by peaceful, contented contemplation.

We can be sympathetic without being pessimists,

and it does not lessen the beauty, nor should it

our appreciation, of Mauve’s work if we find no

“ sense of suffering ” in the two cows the boy is

driving Homeward (page 14), no “undertone of

sadness ” in the woman who comes with her pail to

the cows at Milking Time (page 10), poetry but no

melancholy in the Interior of a Barn (frontispiece).

To have nothing better to think about this last

than the melancholy fact that sheep are fed and

kept warm only that they may afford raiment

and food for man, is to read a false literary

motive into a work that has a true pictorial

appeal. We must not confuse what may happen

to interest us with what primarily interests the

painter, light giving colour to form.

I imagine this melancholy misconception about

Mauve originally arose from some critic observing

that his tendency was epic rather than lyric. And

since epic to many suggests sorrow and suffering,

just as lyric does joy and gladness, the rest was

easy. Then by another association of ideas, that

of sorrow with shadow, a second misconception

was brought to birth, and the “ sorrow-laden ” work

of Mauve wras spoken of uniformly as low-toned.

Now all tones are relative, and a middle period

Mauve may be low in tone compared to a late

Turner or a Monet; but it is high compared to a

Rembrandt or a Jacob Maris. With a Boudin it

is about on a level, and Boudin is not usually

considered a low-toned painter. The truth is that

Mauve, beginning in the bass, played for the best

part of his life on the middle notes of the colour

scale. There are low-toned paintings by him just

as there are in some of them figures, like the

tired, worn peasant of the Shepherd and Flock

(supplement), which do convey a sense of sad

endurance. Still the characteristics of a painter’s

art are not to be deduced from isolated examples,

but from the bulk of his work; and to look

without preconceived notions at a number of

Mauves is to recognise that his painting was

no more low-toned, in the strict sense of the

word, than it as “strongly marked” by the

influence of Millet.

The two chief excellences of Mauve, derived

wholly from the keenness of his own perceptions

and his power to record them aright, are the

BY ANTON MAUVE

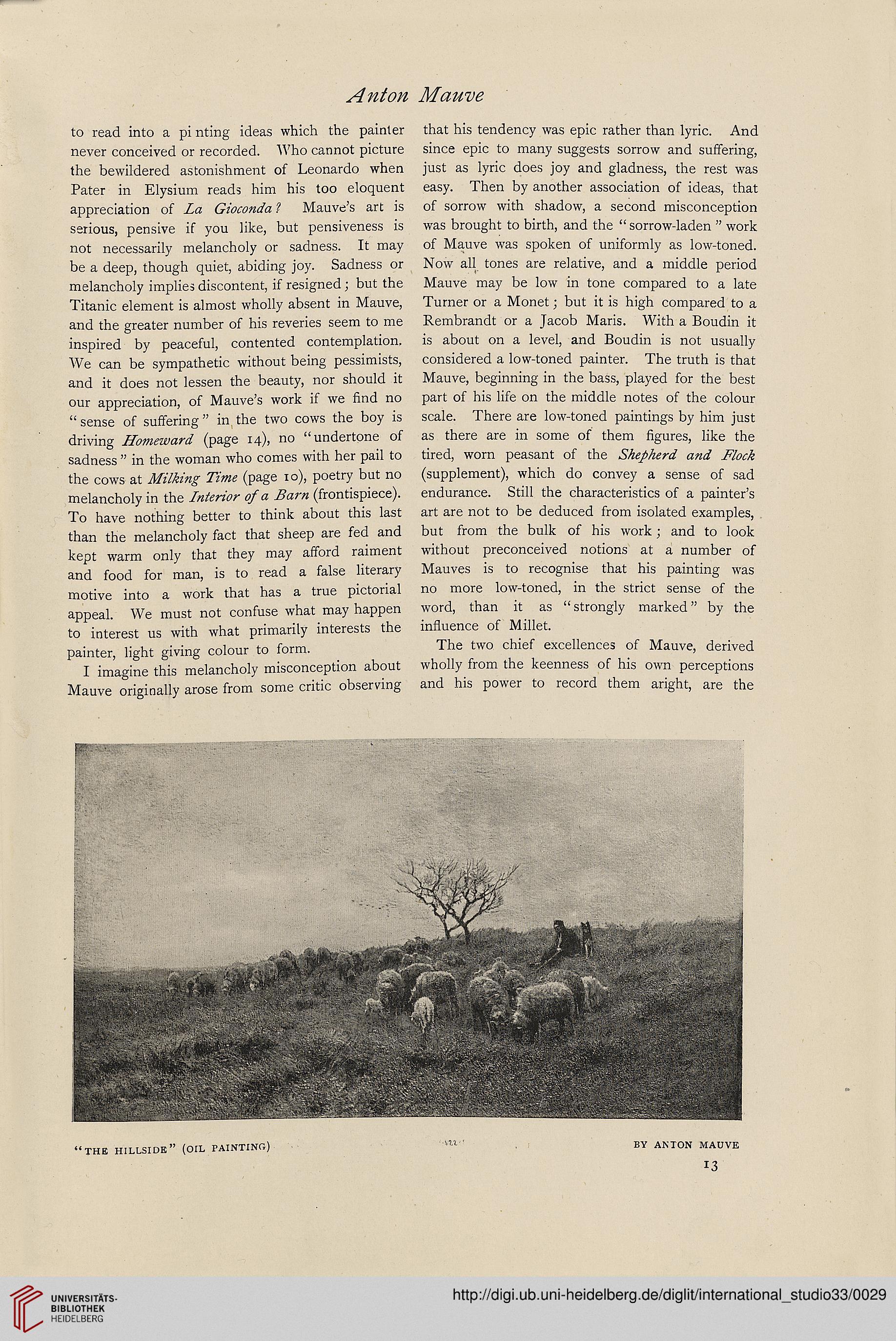

“THE HILLSIDE” (OIL PAINTING)

13

to read into a pi nting ideas which the painter

never conceived or recorded. Who cannot picture

the bewildered astonishment of Leonardo when

Pater in Elysium reads him his too eloquent

appreciation of La Gioconda ? Mauve’s art is

serious, pensive if you like, but pensiveness is

not necessarily melancholy or sadness. It may

be a deep, though quiet, abiding joy. Sadness or

melancholy implies discontent, if resigned; but the

Titanic element is almost wholly absent in Mauve,

and the greater number of his reveries seem to me

inspired by peaceful, contented contemplation.

We can be sympathetic without being pessimists,

and it does not lessen the beauty, nor should it

our appreciation, of Mauve’s work if we find no

“ sense of suffering ” in the two cows the boy is

driving Homeward (page 14), no “undertone of

sadness ” in the woman who comes with her pail to

the cows at Milking Time (page 10), poetry but no

melancholy in the Interior of a Barn (frontispiece).

To have nothing better to think about this last

than the melancholy fact that sheep are fed and

kept warm only that they may afford raiment

and food for man, is to read a false literary

motive into a work that has a true pictorial

appeal. We must not confuse what may happen

to interest us with what primarily interests the

painter, light giving colour to form.

I imagine this melancholy misconception about

Mauve originally arose from some critic observing

that his tendency was epic rather than lyric. And

since epic to many suggests sorrow and suffering,

just as lyric does joy and gladness, the rest was

easy. Then by another association of ideas, that

of sorrow with shadow, a second misconception

was brought to birth, and the “ sorrow-laden ” work

of Mauve wras spoken of uniformly as low-toned.

Now all tones are relative, and a middle period

Mauve may be low in tone compared to a late

Turner or a Monet; but it is high compared to a

Rembrandt or a Jacob Maris. With a Boudin it

is about on a level, and Boudin is not usually

considered a low-toned painter. The truth is that

Mauve, beginning in the bass, played for the best

part of his life on the middle notes of the colour

scale. There are low-toned paintings by him just

as there are in some of them figures, like the

tired, worn peasant of the Shepherd and Flock

(supplement), which do convey a sense of sad

endurance. Still the characteristics of a painter’s

art are not to be deduced from isolated examples,

but from the bulk of his work; and to look

without preconceived notions at a number of

Mauves is to recognise that his painting was

no more low-toned, in the strict sense of the

word, than it as “strongly marked” by the

influence of Millet.

The two chief excellences of Mauve, derived

wholly from the keenness of his own perceptions

and his power to record them aright, are the

BY ANTON MAUVE

“THE HILLSIDE” (OIL PAINTING)

13