The Washington Plan

leans by Bienville; the plans of both are artistic

and practical, and may be advantageously con-

trasted with those of New York and Chicago,

which merely exhibit the ability of certain draughts-

men to handle a straight-edge and a ruling pen.

Another distinction of the original Washington

plan was that it provided appropriate setting for

the public buildings—the Capitol was placed upon

an eminence so that from every point it might be-

come a dominant feature in the city’s composition;

the President’s house was located in a different

section of the city and placed back from the street,

while the Mall was reserved to furnish sites for

semipublic edifices. All this was undoubtedly done

with an eye to effect—the parking was intended to

serve as a frame to the architectural picture, and

the space thus reserved made sufficient to insure

ample perspective. Sir Christopher Wren once

complained that public buildings were of necessity

generally seen sideways, and it is true that greed of

ground prevents the public from looking many

squarely in the face.

And, furthermore, it will be seen that L’Enfant’s

plan set forth the advisability of segregating in

groups the buildings for the Federal Government,

the municipality and the public. Around the

Capitol, sites were designated for legislative build-

ings and around the White House, others for

executive offices. It was to an extent the civic center

idea which has only of late years in this country

been advanced or followed. And all these several

parts L’Enfant brought into a carefully related

composition, connecting in a suitable manner the

chief features, considering the immediate need, and

yet providing for future growth and development.

Undoubtedly he drew his inspiration from the great

cities abroad—he was familiar with the work of

Lenotre, and had before him the maps of Paris,

Amsterdam, Frankfort, Strasburg, Orleans, Turin

and Milan as references; but he did not forget the

exigencies of the occasion and the capital which he

planned was well suited to its latitude and to the

needs of the American people.

I have not given so much space, however, to the

original plan of Washington in order to draw

attention to Major L’Enfant’s genius, or to pay

tribute to the wisdom of those who sought his

counsel, but rather because it bears directly upon

the subject in hand and leads to a better under-

standing of that later plan which has in the present

day exerted so potent and benificent an influence.

Nations, like individuals, are prone to forget.

Long before a century has passed L’Enfant’s plan

had been pigeonholed and was being “improved

upon ”; some of the vistas he had carefully planned

were destroyed, a railroad had run its tracks across

the Mall, a Botanic Garden blocked the approach

to the Captol, and the value of continuity was

entirely disregarded. Architecturally and artistic-

ally, things were pretty dark in Washington from

forty-five to ninety-five, as certain public buildings

and monuments erected during that period amply

testify; but the same conditions prevailed elsewhere

as well.

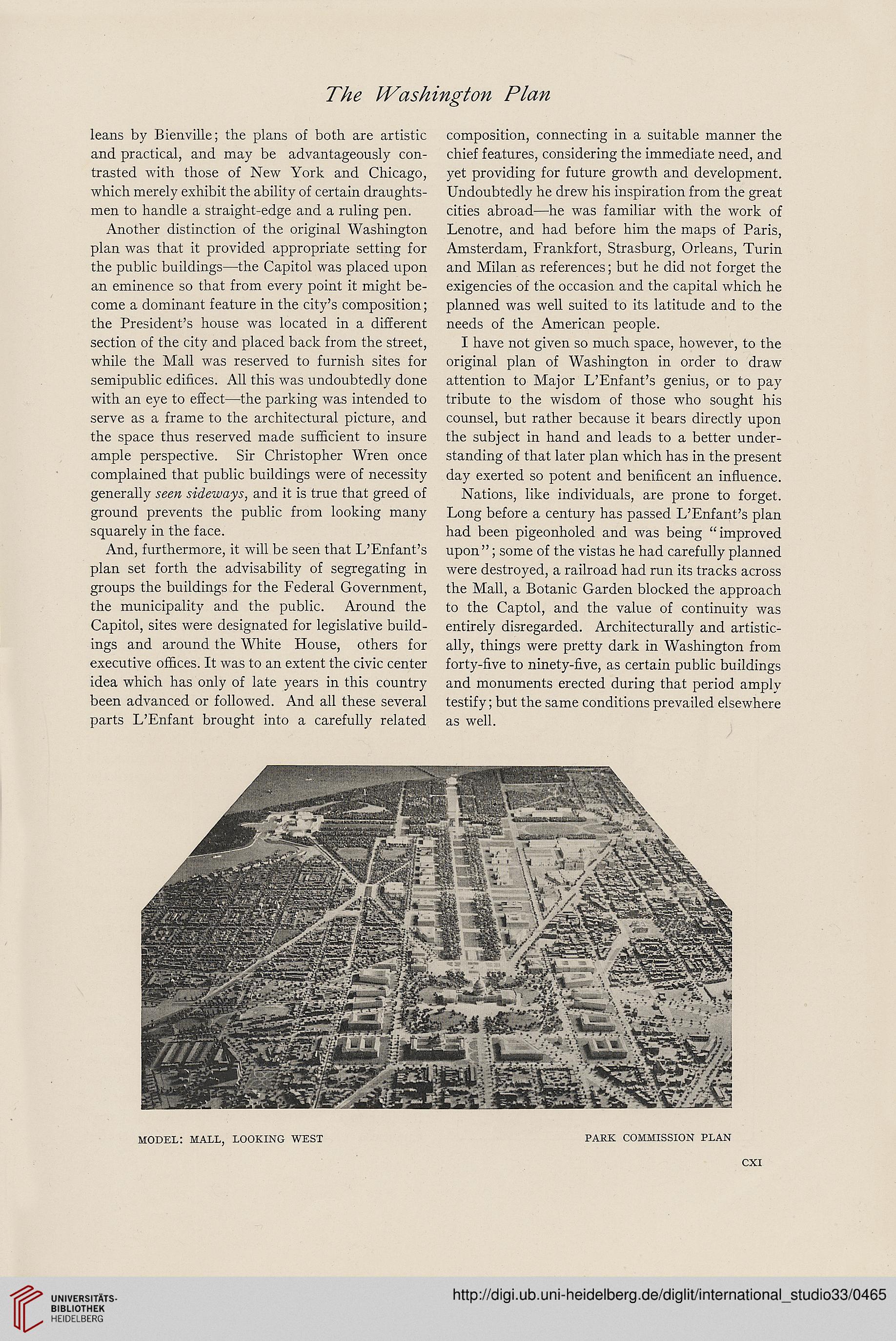

model: mall, looking west

PARK COMMISSION PLAN

leans by Bienville; the plans of both are artistic

and practical, and may be advantageously con-

trasted with those of New York and Chicago,

which merely exhibit the ability of certain draughts-

men to handle a straight-edge and a ruling pen.

Another distinction of the original Washington

plan was that it provided appropriate setting for

the public buildings—the Capitol was placed upon

an eminence so that from every point it might be-

come a dominant feature in the city’s composition;

the President’s house was located in a different

section of the city and placed back from the street,

while the Mall was reserved to furnish sites for

semipublic edifices. All this was undoubtedly done

with an eye to effect—the parking was intended to

serve as a frame to the architectural picture, and

the space thus reserved made sufficient to insure

ample perspective. Sir Christopher Wren once

complained that public buildings were of necessity

generally seen sideways, and it is true that greed of

ground prevents the public from looking many

squarely in the face.

And, furthermore, it will be seen that L’Enfant’s

plan set forth the advisability of segregating in

groups the buildings for the Federal Government,

the municipality and the public. Around the

Capitol, sites were designated for legislative build-

ings and around the White House, others for

executive offices. It was to an extent the civic center

idea which has only of late years in this country

been advanced or followed. And all these several

parts L’Enfant brought into a carefully related

composition, connecting in a suitable manner the

chief features, considering the immediate need, and

yet providing for future growth and development.

Undoubtedly he drew his inspiration from the great

cities abroad—he was familiar with the work of

Lenotre, and had before him the maps of Paris,

Amsterdam, Frankfort, Strasburg, Orleans, Turin

and Milan as references; but he did not forget the

exigencies of the occasion and the capital which he

planned was well suited to its latitude and to the

needs of the American people.

I have not given so much space, however, to the

original plan of Washington in order to draw

attention to Major L’Enfant’s genius, or to pay

tribute to the wisdom of those who sought his

counsel, but rather because it bears directly upon

the subject in hand and leads to a better under-

standing of that later plan which has in the present

day exerted so potent and benificent an influence.

Nations, like individuals, are prone to forget.

Long before a century has passed L’Enfant’s plan

had been pigeonholed and was being “improved

upon ”; some of the vistas he had carefully planned

were destroyed, a railroad had run its tracks across

the Mall, a Botanic Garden blocked the approach

to the Captol, and the value of continuity was

entirely disregarded. Architecturally and artistic-

ally, things were pretty dark in Washington from

forty-five to ninety-five, as certain public buildings

and monuments erected during that period amply

testify; but the same conditions prevailed elsewhere

as well.

model: mall, looking west

PARK COMMISSION PLAN