Recent Work by Frank Brangwyn, A.R.A.

from it the very important truth that the man who

wishes to come to the front by his own force of

character must be consistent in his pursuit of the

ideals which are natural to him—he cannot be

convincing unless he knows his own mind. If he

dallies with strange creeds, if he tries to warp his

inclinations into channels where they do not

instinctively run, if he makes vague experiments

with forms of art in which he does not sincerely

believe, he only wastes his energies and delays his

progress. lie must see definitely ahead the road

he intends to take, and he must fight his way

strenuously along it whatever may be the obstacles

he has to surmount. Indecision cannot but be

fatal to him ; it will destroy the vitality of his art,

and it will make unauthoritative his message to

the world.

Decidedly, Mr. Brangwyn cannot be accused of

having at any moment in his career failed in appre-

ciation of his personal responsibility as an artist.

Not many of our modern masters have so logically

proceeded, stage by stage, to the complete expres-

sion of an individual understanding : few have so

sincerely kept in view, through many busy years,

a deliberate intention to realise certain well-balanced

theories of practice. Now that we have presented

to us the work of what may not unfairly be called

his maturity, the work in which his earlier studies

are bearing their full fruit, we can judge how serious

has been his preparation and how great has been

his care to train himself in refinements of practice

and subtleties of taste. All sides of his art have

been developed together; in acquiring skill of

craftsmanship he has not

forgotten that his hand

must be the servant of his

mind, and that his judg¬

ment, his selective sense,

his aesthetic sentiment

needed equally to be dis¬

ciplined so that his execu¬

tive facility might not lead

him into merely clever

superficiality.

In the work he has pro¬

duced during the last few

years, there are undeniably

a largeness of sentiment

and a depth of feeling

which can be not less

admired than the brilliant

robustness of technique by

which it is distinguished.

He has passed the stage

when the struggle with the mechanism of art

hampers freedom of thought and checks sponta-

neity of expression; his hand has become so

responsive to his intentions that he can trust it to

record fully what is in his mind. He is a master,

too, of practically all the pictorial mediums, of oil

painting, water-colour, tempera, etching, and litho-

graphy, and his drawings are marvels of executive

freedom and suggestive power. The genius of each

medium he entirely respects; he does not try to

strain any of them beyond their correct capabili-

ties, but he uses sometimes one, sometimes

another, as circumstances may demand or as the

character of the particular piece of work on which

he is engaged may indicate. With such a breadth

of resource and with such a command over varie-

ties of mechanism he is never at a loss as to the

way in which he should treat his subjects, to each

one he can give unhesitatingly its appropriate

technical quality.

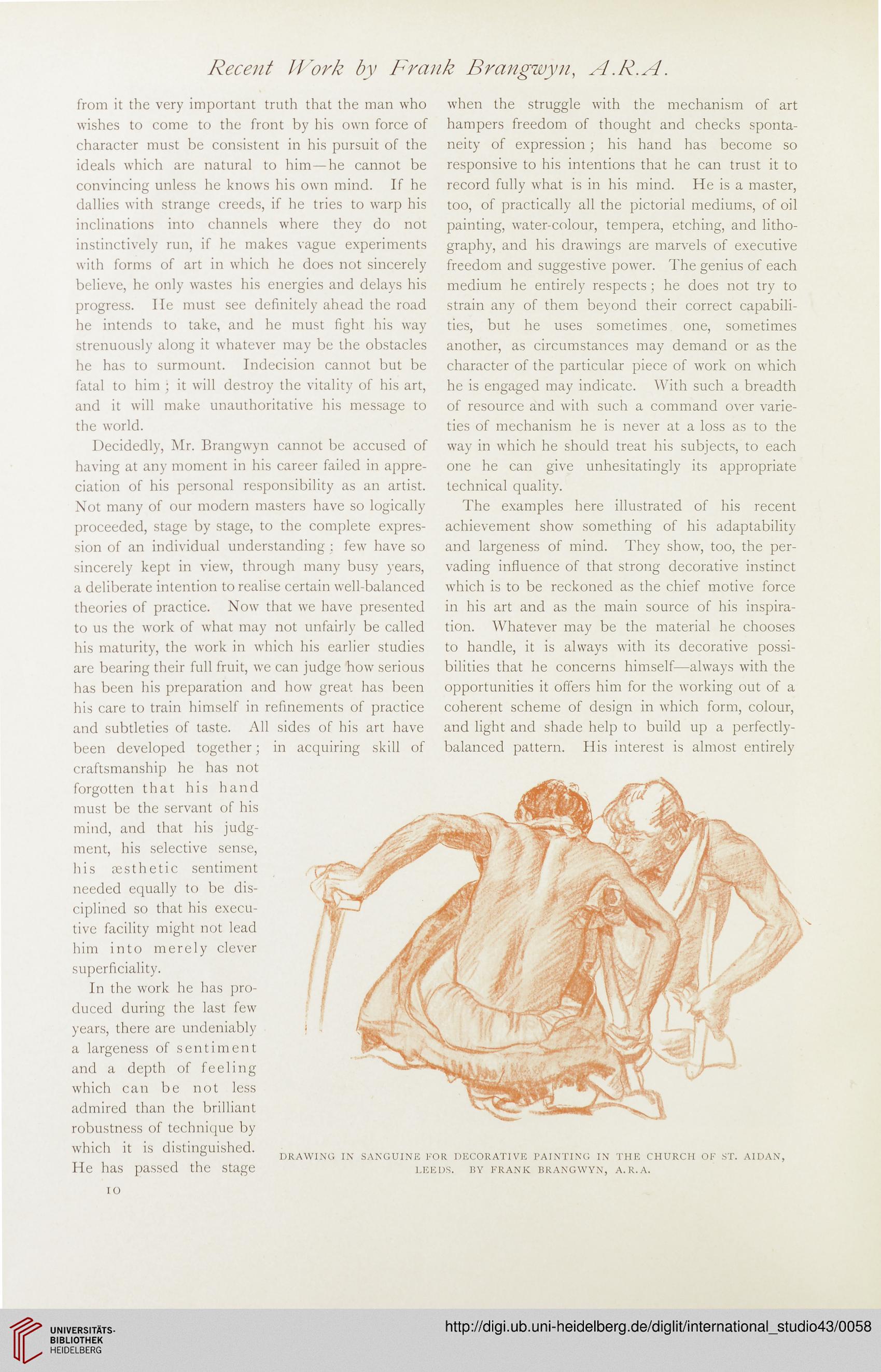

The examples here illustrated of his recent

achievement show something of his adaptability

and largeness of mind. They show, too, the per-

vading influence of that strong decorative instinct

which is to be reckoned as the chief motive force

in his art and as the main source of his inspira-

tion. Whatever may be the material he chooses

to handle, it is always with its decorative possi-

bilities that he concerns himself—always with the

opportunities it offers him for the working out of a

coherent scheme of design in which form, colour,

and light and shade help to build up a perfectly-

balanced pattern. His interest is almost entirely

DRAWING IN SANGUINE FOR DECORATIVE PAINTING IN THE CHURCH OF ST. AIDAN,

LEEDS. BY FRANK BRANGWYN, A.R.A.

IO

from it the very important truth that the man who

wishes to come to the front by his own force of

character must be consistent in his pursuit of the

ideals which are natural to him—he cannot be

convincing unless he knows his own mind. If he

dallies with strange creeds, if he tries to warp his

inclinations into channels where they do not

instinctively run, if he makes vague experiments

with forms of art in which he does not sincerely

believe, he only wastes his energies and delays his

progress. lie must see definitely ahead the road

he intends to take, and he must fight his way

strenuously along it whatever may be the obstacles

he has to surmount. Indecision cannot but be

fatal to him ; it will destroy the vitality of his art,

and it will make unauthoritative his message to

the world.

Decidedly, Mr. Brangwyn cannot be accused of

having at any moment in his career failed in appre-

ciation of his personal responsibility as an artist.

Not many of our modern masters have so logically

proceeded, stage by stage, to the complete expres-

sion of an individual understanding : few have so

sincerely kept in view, through many busy years,

a deliberate intention to realise certain well-balanced

theories of practice. Now that we have presented

to us the work of what may not unfairly be called

his maturity, the work in which his earlier studies

are bearing their full fruit, we can judge how serious

has been his preparation and how great has been

his care to train himself in refinements of practice

and subtleties of taste. All sides of his art have

been developed together; in acquiring skill of

craftsmanship he has not

forgotten that his hand

must be the servant of his

mind, and that his judg¬

ment, his selective sense,

his aesthetic sentiment

needed equally to be dis¬

ciplined so that his execu¬

tive facility might not lead

him into merely clever

superficiality.

In the work he has pro¬

duced during the last few

years, there are undeniably

a largeness of sentiment

and a depth of feeling

which can be not less

admired than the brilliant

robustness of technique by

which it is distinguished.

He has passed the stage

when the struggle with the mechanism of art

hampers freedom of thought and checks sponta-

neity of expression; his hand has become so

responsive to his intentions that he can trust it to

record fully what is in his mind. He is a master,

too, of practically all the pictorial mediums, of oil

painting, water-colour, tempera, etching, and litho-

graphy, and his drawings are marvels of executive

freedom and suggestive power. The genius of each

medium he entirely respects; he does not try to

strain any of them beyond their correct capabili-

ties, but he uses sometimes one, sometimes

another, as circumstances may demand or as the

character of the particular piece of work on which

he is engaged may indicate. With such a breadth

of resource and with such a command over varie-

ties of mechanism he is never at a loss as to the

way in which he should treat his subjects, to each

one he can give unhesitatingly its appropriate

technical quality.

The examples here illustrated of his recent

achievement show something of his adaptability

and largeness of mind. They show, too, the per-

vading influence of that strong decorative instinct

which is to be reckoned as the chief motive force

in his art and as the main source of his inspira-

tion. Whatever may be the material he chooses

to handle, it is always with its decorative possi-

bilities that he concerns himself—always with the

opportunities it offers him for the working out of a

coherent scheme of design in which form, colour,

and light and shade help to build up a perfectly-

balanced pattern. His interest is almost entirely

DRAWING IN SANGUINE FOR DECORATIVE PAINTING IN THE CHURCH OF ST. AIDAN,

LEEDS. BY FRANK BRANGWYN, A.R.A.

IO