Japanese Ornamental Basket Work

and, at the same time,

it is very light, two in-

valuable qualities in port-

able articles ; further, the

twigs of which it is com-

posed will grow on other-

wise worthless land and

practically in a wild state.

Willows, rushes, grasses,

straw, palm stem and leaf,

rattan cane, wistaria, ivy,

bamboo, and other plant

substances, woven in a

vast variety of ways, are

the materials of which it

is composed, and which

are quite distinct from

timber. It therefore will

be seen to constitute a

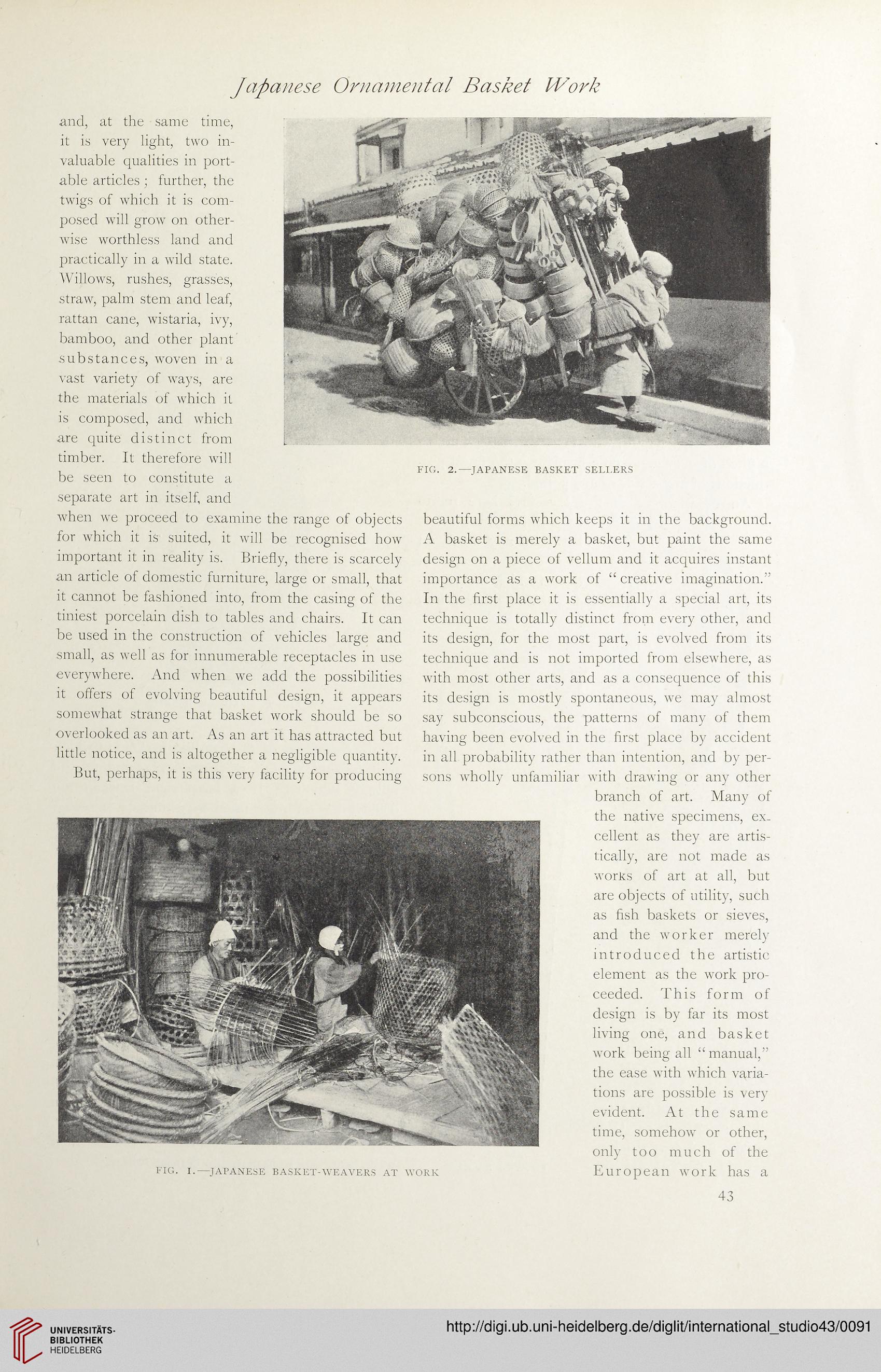

FIG. 2.—JAPANESE BASKET SELLERS

separate art in itself, and

when we proceed to examine the range of objects

for which it is suited, it will be recognised how

important it in reality is. Briefly, there is scarcely

an article of domestic furniture, large or small, that

it cannot be fashioned into, from the casing of the

tiniest porcelain dish to tables and chairs. It can

be used in the construction of vehicles large and

small, as well as for innumerable receptacles in use

everywhere. And when we add the possibilities

it offers of evolving beautiful design, it appears

somewhat strange that basket work should be so

overlooked as an art. As an art it has attracted but

little notice, and is altogether a negligible quantity.

But, perhaps, it is this very facility for producing

beautiful forms which keeps it in the background.

A basket is merely a basket, but paint the same

design on a piece of vellum and it acquires instant

importance as a work of “ creative imagination.”

In the first place it is essentially a special art, its

technique is totally distinct from every other, and

its design, for the most part, is evolved from its

technique and is not imported from elsewhere, as

with most other arts, and as a consequence of this

its design is mostly spontaneous, we may almost

say subconscious, the patterns of many of them

having been evolved in the first place by accident

in all probability rather than intention, and by per-

sons wholly unfamiliar with drawing or any other

branch of art. Many of

the native specimens, ex-

cellent as they are artis-

tically, are not made as

works of art at all, but

are objects of utility, such

as fish baskets or sieves,

and the worker merely

introduced the artistic

element as the work pro-

ceeded. This form of

design is by far its most

living one, and basket

work being all “ manual,”

the ease with which varia-

tions are possible is very

evident. At the same

time, somehow or other,

only too much of the

European work has a

1'IG. I.—JAPANESE BASKET-W'EAVERS AT WORK

43

and, at the same time,

it is very light, two in-

valuable qualities in port-

able articles ; further, the

twigs of which it is com-

posed will grow on other-

wise worthless land and

practically in a wild state.

Willows, rushes, grasses,

straw, palm stem and leaf,

rattan cane, wistaria, ivy,

bamboo, and other plant

substances, woven in a

vast variety of ways, are

the materials of which it

is composed, and which

are quite distinct from

timber. It therefore will

be seen to constitute a

FIG. 2.—JAPANESE BASKET SELLERS

separate art in itself, and

when we proceed to examine the range of objects

for which it is suited, it will be recognised how

important it in reality is. Briefly, there is scarcely

an article of domestic furniture, large or small, that

it cannot be fashioned into, from the casing of the

tiniest porcelain dish to tables and chairs. It can

be used in the construction of vehicles large and

small, as well as for innumerable receptacles in use

everywhere. And when we add the possibilities

it offers of evolving beautiful design, it appears

somewhat strange that basket work should be so

overlooked as an art. As an art it has attracted but

little notice, and is altogether a negligible quantity.

But, perhaps, it is this very facility for producing

beautiful forms which keeps it in the background.

A basket is merely a basket, but paint the same

design on a piece of vellum and it acquires instant

importance as a work of “ creative imagination.”

In the first place it is essentially a special art, its

technique is totally distinct from every other, and

its design, for the most part, is evolved from its

technique and is not imported from elsewhere, as

with most other arts, and as a consequence of this

its design is mostly spontaneous, we may almost

say subconscious, the patterns of many of them

having been evolved in the first place by accident

in all probability rather than intention, and by per-

sons wholly unfamiliar with drawing or any other

branch of art. Many of

the native specimens, ex-

cellent as they are artis-

tically, are not made as

works of art at all, but

are objects of utility, such

as fish baskets or sieves,

and the worker merely

introduced the artistic

element as the work pro-

ceeded. This form of

design is by far its most

living one, and basket

work being all “ manual,”

the ease with which varia-

tions are possible is very

evident. At the same

time, somehow or other,

only too much of the

European work has a

1'IG. I.—JAPANESE BASKET-W'EAVERS AT WORK

43