The Royal Academy Exhibition, 1911

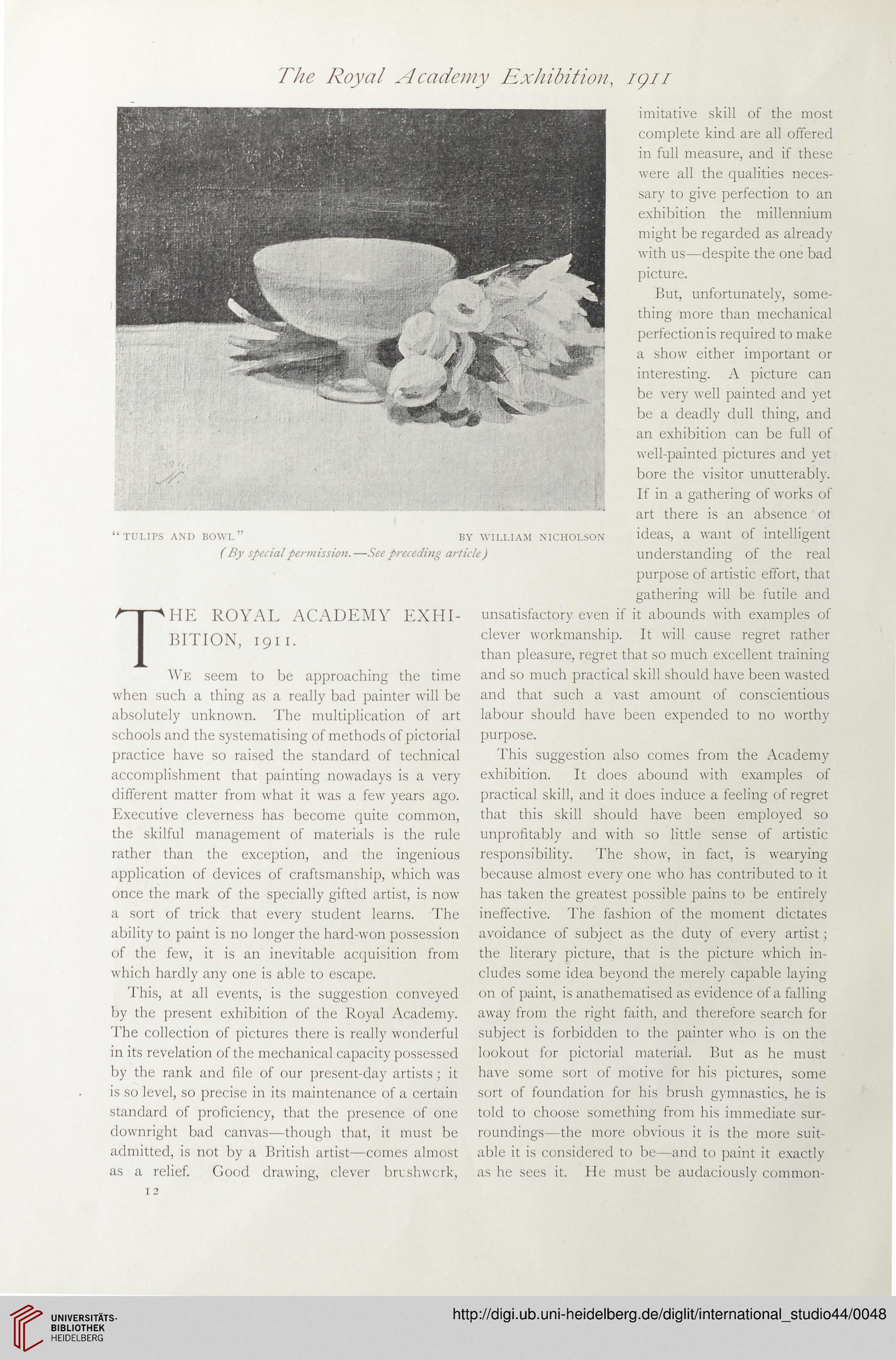

“TULIPS AND bowl” BY WILLIAM NICHOLSON

(By special permission.—See preceding article)

The royal academy exhi-

bition, 1911.

We seem to be approaching the time

when such a thing as a really bad painter will be

absolutely unknown. The multiplication of art

schools and the systematising of methods of pictorial

practice have so raised the standard of technical

accomplishment that painting nowadays is a very

different matter from what it was a few years ago.

Executive cleverness has become quite common,

the skilful management of materials is the rule

rather than the exception, and the ingenious

application of devices of craftsmanship, which was

once the mark of the specially gifted artist, is now

a sort of trick that every student learns. The

ability to paint is no longer the hard-won possession

of the few, it is an inevitable acquisition from

which hardly any one is able to escape.

This, at all events, is the suggestion conveyed

by the present exhibition of the Royal Academy,

'bhe collection of pictures there is really wonderful

in its revelation of the mechanical capacity possessed

by the rank and file of our present-day artists; it

is so level, so precise in its maintenance of a certain

standard of proficiency, that the presence of one

downright bad canvas—though that, it must be

admitted, is not by a British artist—comes almost

as a relief. Good drawing, clever brushwcrk,

imitative skill of the most

complete kind are all offered

in full measure, and if these

were all the qualities neces-

sary to give perfection to an

exhibition the millennium

might be regarded as already

with us—despite the one bad

picture.

But, unfortunately, some-

thing more than mechanical

perfection is required to make

a show either important or

interesting. A picture can

be very well painted and yet

be a deadly dull thing, and

an exhibition can be full of

well-painted pictures and yet

bore the visitor unutterably.

If in a gathering of works of

art there is an absence ot

ideas, a want of intelligent

understanding of the real

purpose of artistic effort, that

gathering will be futile and

unsatisfactory even if it abounds with examples of

clever workmanship. It will cause regret rather

than pleasure, regret that so much excellent training

and so much practical skill should have been wasted

and that such a vast amount of conscientious

labour should have been expended to no worthy

purpose.

This suggestion also comes from the Academy

exhibition. It does abound with examples of

practical skill, and it does induce a feeling of regret

that this skill should have been employed so

unprofitably and with so little sense of artistic

responsibility. The show, in fact, is wearying

because almost every one who has contributed to it

has taken the greatest possible pains to be entirely

ineffective. The fashion of the moment dictates

avoidance of subject as the duty of every artist;

the literary picture, that is the picture which in-

cludes some idea beyond the merely capable laying

on of paint, is anathematised as evidence of a falling

away from the right faith, and therefore search for

subject is forbidden to the painter who is on the

lookout for pictorial material. But as he must

have some sort of motive for his pictures, some

sort of foundation for his brush gymnastics, he is

told to choose something from his immediate sur-

roundings—the more obvious it is the more suit-

able it is considered to be—and to paint it exactly

as he sees it. He must be audaciously common-

12

“TULIPS AND bowl” BY WILLIAM NICHOLSON

(By special permission.—See preceding article)

The royal academy exhi-

bition, 1911.

We seem to be approaching the time

when such a thing as a really bad painter will be

absolutely unknown. The multiplication of art

schools and the systematising of methods of pictorial

practice have so raised the standard of technical

accomplishment that painting nowadays is a very

different matter from what it was a few years ago.

Executive cleverness has become quite common,

the skilful management of materials is the rule

rather than the exception, and the ingenious

application of devices of craftsmanship, which was

once the mark of the specially gifted artist, is now

a sort of trick that every student learns. The

ability to paint is no longer the hard-won possession

of the few, it is an inevitable acquisition from

which hardly any one is able to escape.

This, at all events, is the suggestion conveyed

by the present exhibition of the Royal Academy,

'bhe collection of pictures there is really wonderful

in its revelation of the mechanical capacity possessed

by the rank and file of our present-day artists; it

is so level, so precise in its maintenance of a certain

standard of proficiency, that the presence of one

downright bad canvas—though that, it must be

admitted, is not by a British artist—comes almost

as a relief. Good drawing, clever brushwcrk,

imitative skill of the most

complete kind are all offered

in full measure, and if these

were all the qualities neces-

sary to give perfection to an

exhibition the millennium

might be regarded as already

with us—despite the one bad

picture.

But, unfortunately, some-

thing more than mechanical

perfection is required to make

a show either important or

interesting. A picture can

be very well painted and yet

be a deadly dull thing, and

an exhibition can be full of

well-painted pictures and yet

bore the visitor unutterably.

If in a gathering of works of

art there is an absence ot

ideas, a want of intelligent

understanding of the real

purpose of artistic effort, that

gathering will be futile and

unsatisfactory even if it abounds with examples of

clever workmanship. It will cause regret rather

than pleasure, regret that so much excellent training

and so much practical skill should have been wasted

and that such a vast amount of conscientious

labour should have been expended to no worthy

purpose.

This suggestion also comes from the Academy

exhibition. It does abound with examples of

practical skill, and it does induce a feeling of regret

that this skill should have been employed so

unprofitably and with so little sense of artistic

responsibility. The show, in fact, is wearying

because almost every one who has contributed to it

has taken the greatest possible pains to be entirely

ineffective. The fashion of the moment dictates

avoidance of subject as the duty of every artist;

the literary picture, that is the picture which in-

cludes some idea beyond the merely capable laying

on of paint, is anathematised as evidence of a falling

away from the right faith, and therefore search for

subject is forbidden to the painter who is on the

lookout for pictorial material. But as he must

have some sort of motive for his pictures, some

sort of foundation for his brush gymnastics, he is

told to choose something from his immediate sur-

roundings—the more obvious it is the more suit-

able it is considered to be—and to paint it exactly

as he sees it. He must be audaciously common-

12