Alfred Stieglitz

phy is more or less a delusion and a snare. It is

too new, too recent, too much a real part of the

logical development of contemporary life and

comes a bit too proudly and unconventionally to

be understood and accepted of its own time.

As a little clue I would simply throw out the

observation that the highest expression of the

imaginative and inventive genius of our time, espe-

cially of the best creative minds of America, is the

machine, in all its beautiful simplicity and coor-

dinate complexity; in it we find our sonnets, our

epics, and therein lies expressed eloquently the

true greatness of our age. Why, then, shouldn’t

some of our most sensitive, progressive and, in the

best sense, truly modern minds find in this exqui-

sitely sensitive machine, the camera, an instrument

responsive as none other to express what they feel

and see of the beauty and glory of life? Yours,

gentle but stubborn reader, is the onus, not mine,

and I leave you to answer it as best you may. As

for me, the work of Alfred Stieglitz confirms in the

most positive fashion that photography is such a

medium of expression. In his work is admirably

illustrated the evolution of pictorial photography,

from its most tentative struggle for self-expression

down to its most recent achievements that are

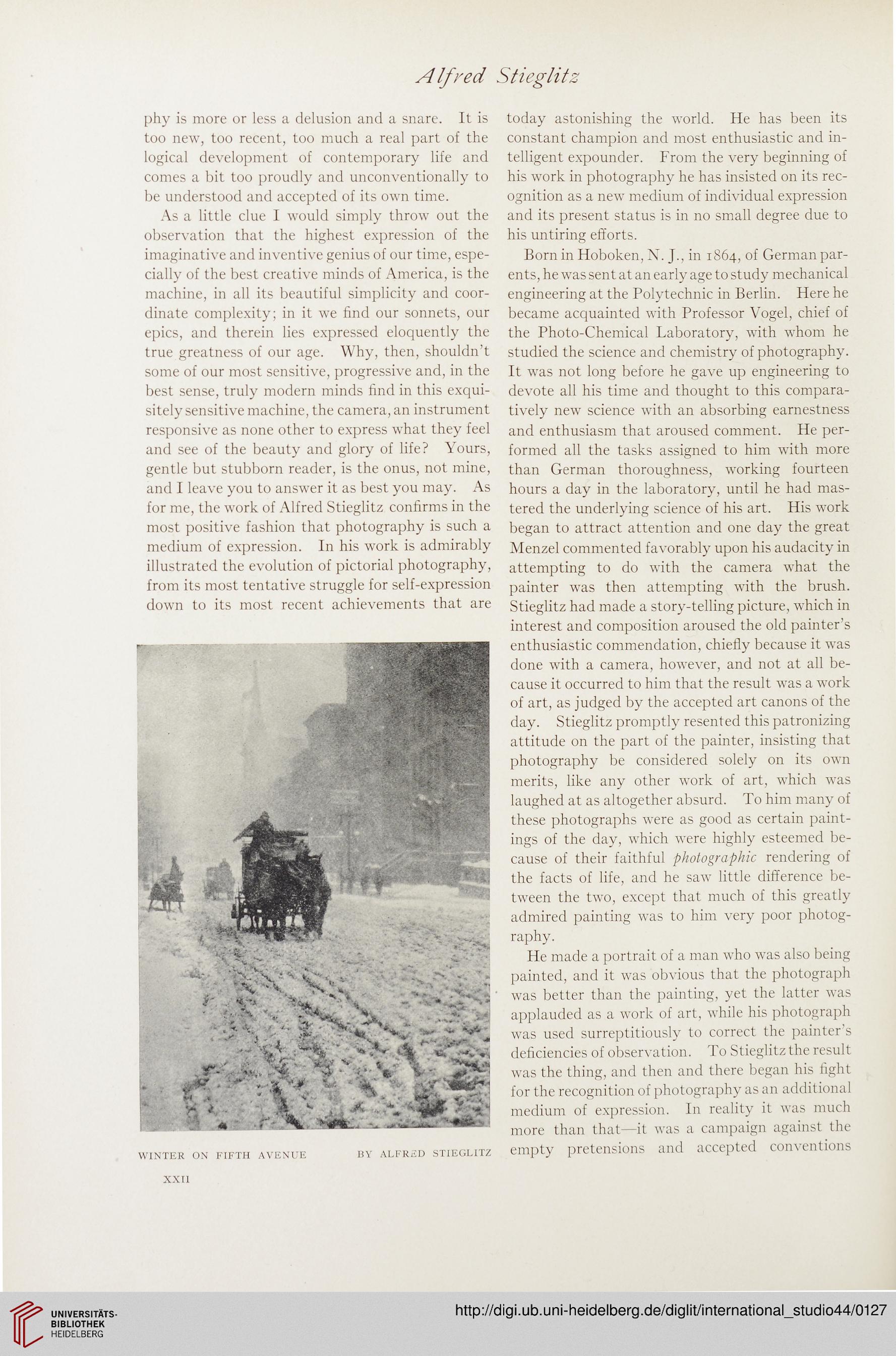

WINTER ON FIFTH AVENUE

BY ALFRED STIEGLITZ

today astonishing the world. He has been its

constant champion and most enthusiastic and in-

telligent expounder. From the very beginning of

his work in photography he has insisted on its rec-

ognition as a new medium of individual expression

and its present status is in no small degree due to

his untiring efforts.

Born in Hoboken, N. J., in 1864, of German par-

ents, he was sent at an early age to study mechanical

engineering at the Polytechnic in Berlin. Here he

became acquainted with Professor Vogel, chief of

the Photo-Chemical Laboratory, with whom he

studied the science and chemistry of photography.

It was not long before he gave up engineering to

devote all his time and thought to this compara-

tively new science with an absorbing earnestness

and enthusiasm that aroused comment. He per-

formed all the tasks assigned to him with more

than German thoroughness, working fourteen

hours a day in the laboratory, until he had mas-

tered the underlying science of his art. His work

began to attract attention and one day the great

Menzel commented favorably upon his audacity in

attempting to do with the camera what the

painter was then attempting with the brush.

Stieglitz had made a story-telling picture, which in

interest and composition aroused the old painter’s

enthusiastic commendation, chiefly because it was

done with a camera, however, and not at all be-

cause it occurred to him that the result was a work

of art, as judged by the accepted art canons of the

day. Stieglitz promptly resented this patronizing

attitude on the part of the painter, insisting that

photography be considered solely on its own

merits, like any other work of art, which was

laughed at as altogether absurd. To him many of

these photographs were as good as certain paint-

ings of the day, which were highly esteemed be-

cause of their faithful photographic rendering of

the facts of life, and he saw little difference be-

tween the two, except that much of this greatly

admired painting was to him very poor photog-

raphy.

He made a portrait of a man who was also being

painted, and it was obvious that the photograph

was better than the painting, yet the latter was

applauded as a work of art, while his photograph

was used surreptitiously to correct the painter’s

deficiencies of observation. To Stieglitz the result

was the thing, and then and there began his fight

for the recognition of photography as an additional

medium of expression. In reality it was much

more than that—it was a campaign against the

empty pretensions and accepted conventions

XXII

phy is more or less a delusion and a snare. It is

too new, too recent, too much a real part of the

logical development of contemporary life and

comes a bit too proudly and unconventionally to

be understood and accepted of its own time.

As a little clue I would simply throw out the

observation that the highest expression of the

imaginative and inventive genius of our time, espe-

cially of the best creative minds of America, is the

machine, in all its beautiful simplicity and coor-

dinate complexity; in it we find our sonnets, our

epics, and therein lies expressed eloquently the

true greatness of our age. Why, then, shouldn’t

some of our most sensitive, progressive and, in the

best sense, truly modern minds find in this exqui-

sitely sensitive machine, the camera, an instrument

responsive as none other to express what they feel

and see of the beauty and glory of life? Yours,

gentle but stubborn reader, is the onus, not mine,

and I leave you to answer it as best you may. As

for me, the work of Alfred Stieglitz confirms in the

most positive fashion that photography is such a

medium of expression. In his work is admirably

illustrated the evolution of pictorial photography,

from its most tentative struggle for self-expression

down to its most recent achievements that are

WINTER ON FIFTH AVENUE

BY ALFRED STIEGLITZ

today astonishing the world. He has been its

constant champion and most enthusiastic and in-

telligent expounder. From the very beginning of

his work in photography he has insisted on its rec-

ognition as a new medium of individual expression

and its present status is in no small degree due to

his untiring efforts.

Born in Hoboken, N. J., in 1864, of German par-

ents, he was sent at an early age to study mechanical

engineering at the Polytechnic in Berlin. Here he

became acquainted with Professor Vogel, chief of

the Photo-Chemical Laboratory, with whom he

studied the science and chemistry of photography.

It was not long before he gave up engineering to

devote all his time and thought to this compara-

tively new science with an absorbing earnestness

and enthusiasm that aroused comment. He per-

formed all the tasks assigned to him with more

than German thoroughness, working fourteen

hours a day in the laboratory, until he had mas-

tered the underlying science of his art. His work

began to attract attention and one day the great

Menzel commented favorably upon his audacity in

attempting to do with the camera what the

painter was then attempting with the brush.

Stieglitz had made a story-telling picture, which in

interest and composition aroused the old painter’s

enthusiastic commendation, chiefly because it was

done with a camera, however, and not at all be-

cause it occurred to him that the result was a work

of art, as judged by the accepted art canons of the

day. Stieglitz promptly resented this patronizing

attitude on the part of the painter, insisting that

photography be considered solely on its own

merits, like any other work of art, which was

laughed at as altogether absurd. To him many of

these photographs were as good as certain paint-

ings of the day, which were highly esteemed be-

cause of their faithful photographic rendering of

the facts of life, and he saw little difference be-

tween the two, except that much of this greatly

admired painting was to him very poor photog-

raphy.

He made a portrait of a man who was also being

painted, and it was obvious that the photograph

was better than the painting, yet the latter was

applauded as a work of art, while his photograph

was used surreptitiously to correct the painter’s

deficiencies of observation. To Stieglitz the result

was the thing, and then and there began his fight

for the recognition of photography as an additional

medium of expression. In reality it was much

more than that—it was a campaign against the

empty pretensions and accepted conventions

XXII