Sir James Guthrie, P.R.S.A.

acquaintance with the work of the French and

Dutch romanticists . . . and the training received

in Paris.” Whatever the influences, the revolution

began, and from the moment that the canvases of

Guthrie and his confederates began to appear the

result seemed inevitable. The point of view of the

discriminating public changed rapidly, not only in

its attitude towards art but towards nature. For

though art is not the imitator of nature, it is its

revealer. The human sight is no fixed quantity;

the uneducated vision is not a camera displaying

the complete truth. The artist is to the man of

common vision as a mystic medium through which

nature is transformed by whatever light the artist

possesses. He is akin to the poet who glorifies

the commonplace in the language of an inspired

seer. He is a Keats, a Burns, a Browning of the

brush, as different from Brown, Jones, and Robinson

as a play of FEschylus is from an Adelphi melo-

drama, or a novel of George Meredith from a

bookstall yellow-back. “I can’t see nature like

that,” remarked a philistine to Whistler. “ Don’t

you wish you could ? ” was the painter’s reply.

When Guthrie and his confreres first began to

paint, the ignorant cried out that this was not

nature, being unaware that they were as ignorant

of nature as they were of art. As soon as

the great painters reveal their secrets to

us, nature as well as art takes on a

different meaning. A man who has

studied the wonderful canvases of William

McTaggart can never look upon the sea

as he did before ; he who has intelligently

viewed a portrait by Sir James Guthrie

has learned a lesson in regarding

humanity which can never cease to affect

his vision.

Distinction in style, a reaching towards

naturalistic values in the shape of tone

and plein air, a minimising of the non-

essentials and a definite striving towards

the realisation of true pictorial elements

-—these were some of the ideals of Guthrie

and the new school. The bald transcrip-

tion of evident and unrelated facts, the

careful insertion of trivial and accidental

points, the painting of landscapes as if

they were interiors, without a complete

interrelation between earth and atmo-

sphere, no indivisible unity of the colour-

scheme throughout the picture, laying

down a portrait on a background having

no significance in the general scheme—

all this was put aside for the great aim of

presenting a design which met the eye as

a perfect symphony or an inspired lyric

meets the ear. There was nothing finick-

ing or petty; everything was full, deep,

significant. The new men went to

nature, not to catalogue or classify, but

to select, interpret, and clarify. Between

nature and the canvas they put the vision

and the personality of the seer and trans-

lated their images in the colossal cypher

of the colourist. Of course the ambition

often failed. There wras occasionally

found chaos instead of cosmos and there

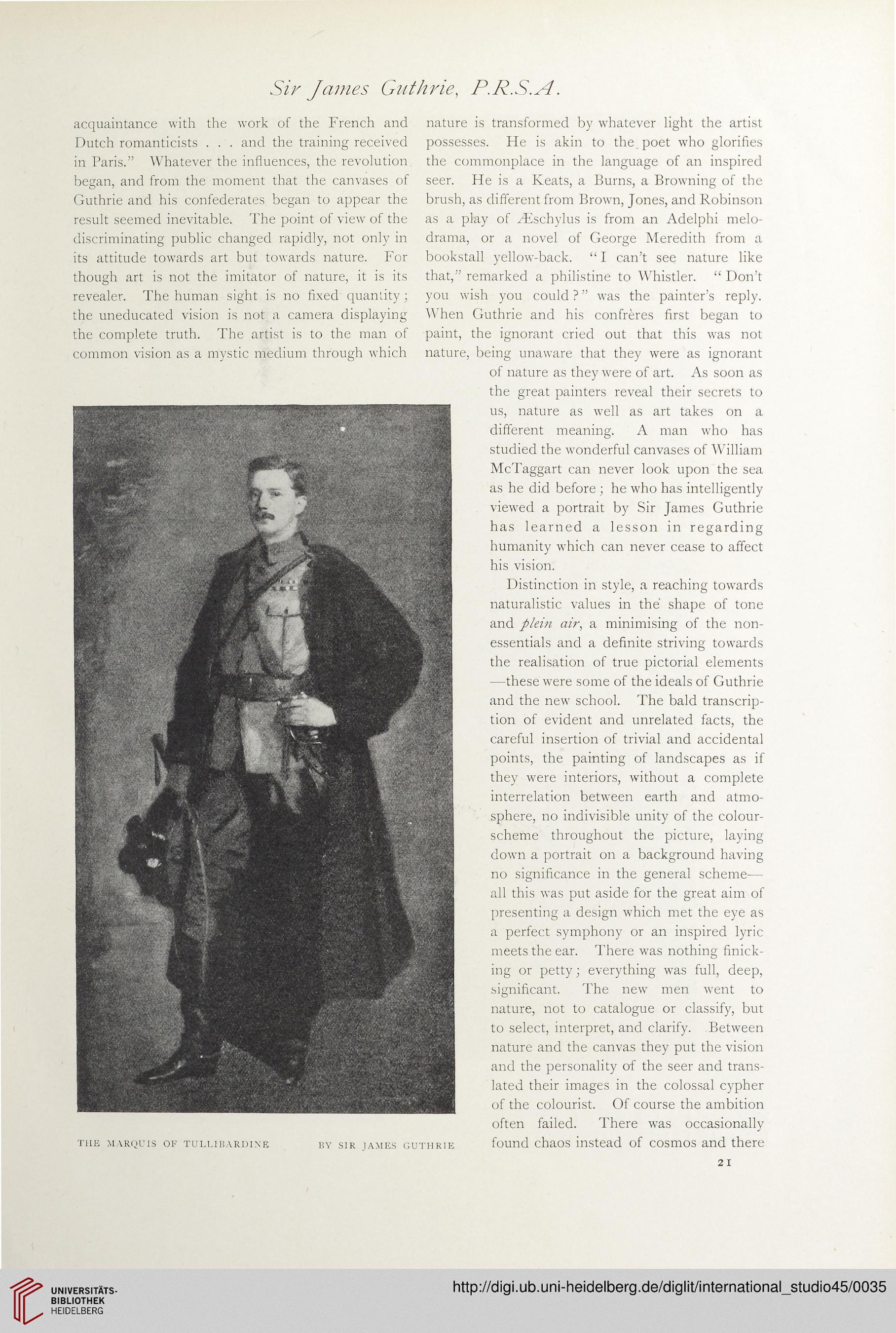

THE M ARQUIS OF TULI.IBARD1 X E

BY SIR JAMES GUTHRIE

21

acquaintance with the work of the French and

Dutch romanticists . . . and the training received

in Paris.” Whatever the influences, the revolution

began, and from the moment that the canvases of

Guthrie and his confederates began to appear the

result seemed inevitable. The point of view of the

discriminating public changed rapidly, not only in

its attitude towards art but towards nature. For

though art is not the imitator of nature, it is its

revealer. The human sight is no fixed quantity;

the uneducated vision is not a camera displaying

the complete truth. The artist is to the man of

common vision as a mystic medium through which

nature is transformed by whatever light the artist

possesses. He is akin to the poet who glorifies

the commonplace in the language of an inspired

seer. He is a Keats, a Burns, a Browning of the

brush, as different from Brown, Jones, and Robinson

as a play of FEschylus is from an Adelphi melo-

drama, or a novel of George Meredith from a

bookstall yellow-back. “I can’t see nature like

that,” remarked a philistine to Whistler. “ Don’t

you wish you could ? ” was the painter’s reply.

When Guthrie and his confreres first began to

paint, the ignorant cried out that this was not

nature, being unaware that they were as ignorant

of nature as they were of art. As soon as

the great painters reveal their secrets to

us, nature as well as art takes on a

different meaning. A man who has

studied the wonderful canvases of William

McTaggart can never look upon the sea

as he did before ; he who has intelligently

viewed a portrait by Sir James Guthrie

has learned a lesson in regarding

humanity which can never cease to affect

his vision.

Distinction in style, a reaching towards

naturalistic values in the shape of tone

and plein air, a minimising of the non-

essentials and a definite striving towards

the realisation of true pictorial elements

-—these were some of the ideals of Guthrie

and the new school. The bald transcrip-

tion of evident and unrelated facts, the

careful insertion of trivial and accidental

points, the painting of landscapes as if

they were interiors, without a complete

interrelation between earth and atmo-

sphere, no indivisible unity of the colour-

scheme throughout the picture, laying

down a portrait on a background having

no significance in the general scheme—

all this was put aside for the great aim of

presenting a design which met the eye as

a perfect symphony or an inspired lyric

meets the ear. There was nothing finick-

ing or petty; everything was full, deep,

significant. The new men went to

nature, not to catalogue or classify, but

to select, interpret, and clarify. Between

nature and the canvas they put the vision

and the personality of the seer and trans-

lated their images in the colossal cypher

of the colourist. Of course the ambition

often failed. There wras occasionally

found chaos instead of cosmos and there

THE M ARQUIS OF TULI.IBARD1 X E

BY SIR JAMES GUTHRIE

21