Old Japanese Folding Screens

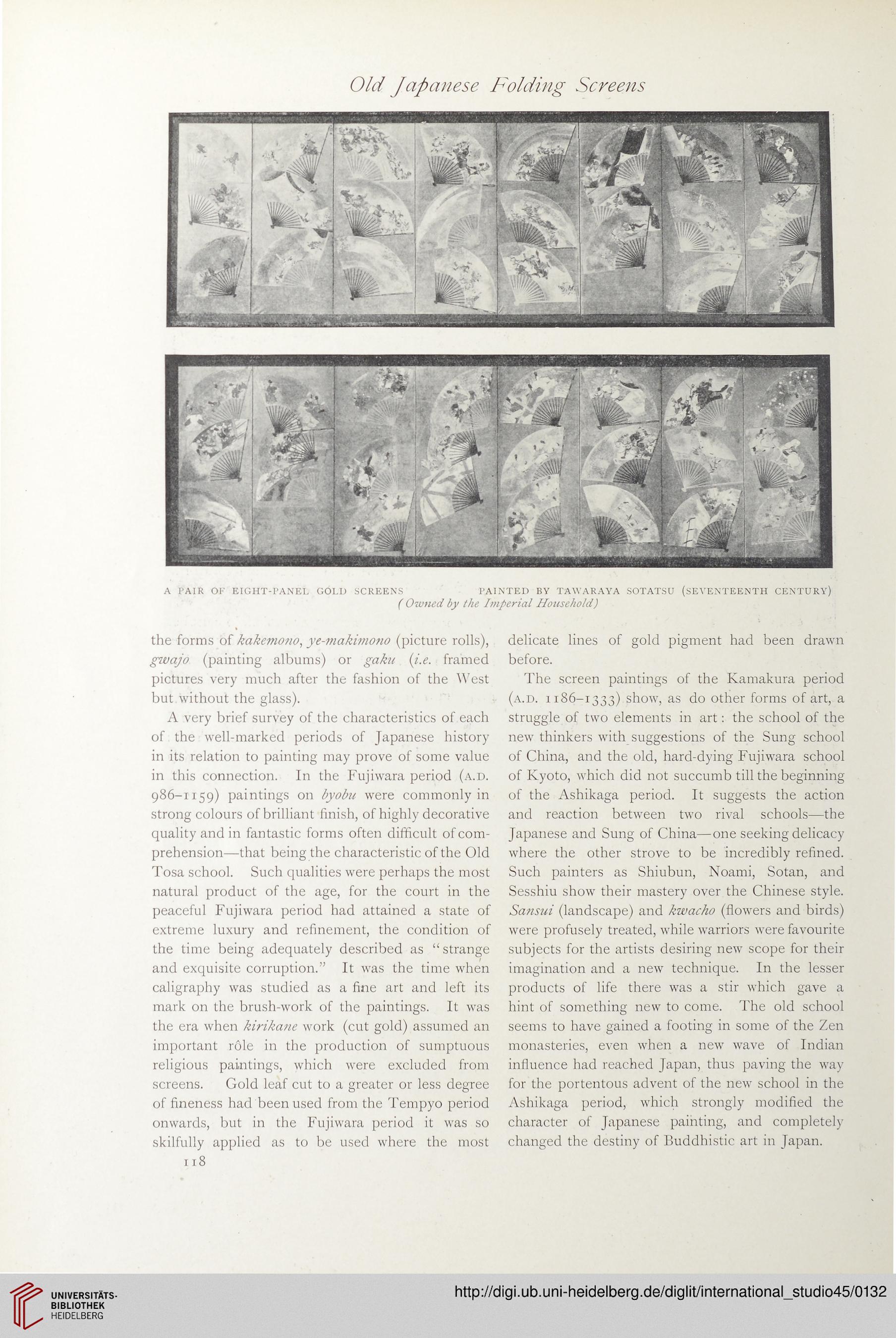

A PAIR OF EIGHT-PANEL GOLD SCREENS PAINTED BY TAWARAYA SOTATSU (SEVENTEENTH CENTURY)

( Owned by the Imperial Household)

the forms of kakemono, ye-makimono (picture rolls),

gwajo (painting albums) or gaku (i.e. framed

pictures very much after the fashion of the West

but without the glass).

A very brief survey of the characteristics of each

of the well-marked periods of Japanese history

in its relation to painting may prove of some value

in this connection. In the Fujiwara period (a.d.

986-1159) paintings on byobu were commonly in

strong colours of brilliant finish, of highly decorative

quality and in fantastic forms often difficult of com-

prehension—that being the characteristic of the Old

Tosa school. Such qualities were perhaps the most

natural product of the age, for the court in the

peaceful Fujiwara period had attained a state of

extreme luxury and refinement, the condition of

the time being adequately described as “ strange

and exquisite corruption.” It was the time when

caligraphy was studied as a fine art and left its

mark on the brush-work of the paintings. It was

the era when kirikane work (cut gold) assumed an

important role in the production of sumptuous

religious paintings, which were excluded from

screens. Gold leaf cut to a greater or less degree

of fineness had been used from the Tempyo period

onwards, but in the Fujiwara period it was so

skilfully applied as to be used where the most

118

delicate lines of gold pigment had been drawn

before.

The screen paintings of the Kamakura period

(a.d. 1186-1333) show, as do other forms of art, a

struggle of two elements in art: the school of the

new thinkers with suggestions of the Sung school

of China, and the old, hard-dying Fujiwara school

of Kyoto, which did not succumb till the beginning

of the Ashikaga period. It suggests the action

and reaction between two rival schools—the

Japanese and Sung of China—one seeking delicacy

where the other strove to be incredibly refined.

Such painters as Shiubun, Noami, Sotan, and

Sesshiu show their mastery over the Chinese style.

Sansui (landscape) and kwacho (flowers and birds)

were profusely treated, while warriors were favourite

subjects for the artists desiring new scope for their

imagination and a new technique. In the lesser

products of life there was a stir which gave a

hint of something new to come. The old school

seems to have gained a footing in some of the Zen

monasteries, even when a new wave of Indian

influence had reached Japan, thus paving the way

for the portentous advent of the new school in the

Ashikaga period, which strongly modified the

character of Japanese painting, and completely

changed the destiny of Buddhistic art in Japan.

A PAIR OF EIGHT-PANEL GOLD SCREENS PAINTED BY TAWARAYA SOTATSU (SEVENTEENTH CENTURY)

( Owned by the Imperial Household)

the forms of kakemono, ye-makimono (picture rolls),

gwajo (painting albums) or gaku (i.e. framed

pictures very much after the fashion of the West

but without the glass).

A very brief survey of the characteristics of each

of the well-marked periods of Japanese history

in its relation to painting may prove of some value

in this connection. In the Fujiwara period (a.d.

986-1159) paintings on byobu were commonly in

strong colours of brilliant finish, of highly decorative

quality and in fantastic forms often difficult of com-

prehension—that being the characteristic of the Old

Tosa school. Such qualities were perhaps the most

natural product of the age, for the court in the

peaceful Fujiwara period had attained a state of

extreme luxury and refinement, the condition of

the time being adequately described as “ strange

and exquisite corruption.” It was the time when

caligraphy was studied as a fine art and left its

mark on the brush-work of the paintings. It was

the era when kirikane work (cut gold) assumed an

important role in the production of sumptuous

religious paintings, which were excluded from

screens. Gold leaf cut to a greater or less degree

of fineness had been used from the Tempyo period

onwards, but in the Fujiwara period it was so

skilfully applied as to be used where the most

118

delicate lines of gold pigment had been drawn

before.

The screen paintings of the Kamakura period

(a.d. 1186-1333) show, as do other forms of art, a

struggle of two elements in art: the school of the

new thinkers with suggestions of the Sung school

of China, and the old, hard-dying Fujiwara school

of Kyoto, which did not succumb till the beginning

of the Ashikaga period. It suggests the action

and reaction between two rival schools—the

Japanese and Sung of China—one seeking delicacy

where the other strove to be incredibly refined.

Such painters as Shiubun, Noami, Sotan, and

Sesshiu show their mastery over the Chinese style.

Sansui (landscape) and kwacho (flowers and birds)

were profusely treated, while warriors were favourite

subjects for the artists desiring new scope for their

imagination and a new technique. In the lesser

products of life there was a stir which gave a

hint of something new to come. The old school

seems to have gained a footing in some of the Zen

monasteries, even when a new wave of Indian

influence had reached Japan, thus paving the way

for the portentous advent of the new school in the

Ashikaga period, which strongly modified the

character of Japanese painting, and completely

changed the destiny of Buddhistic art in Japan.