Old Japanese Folding Screens

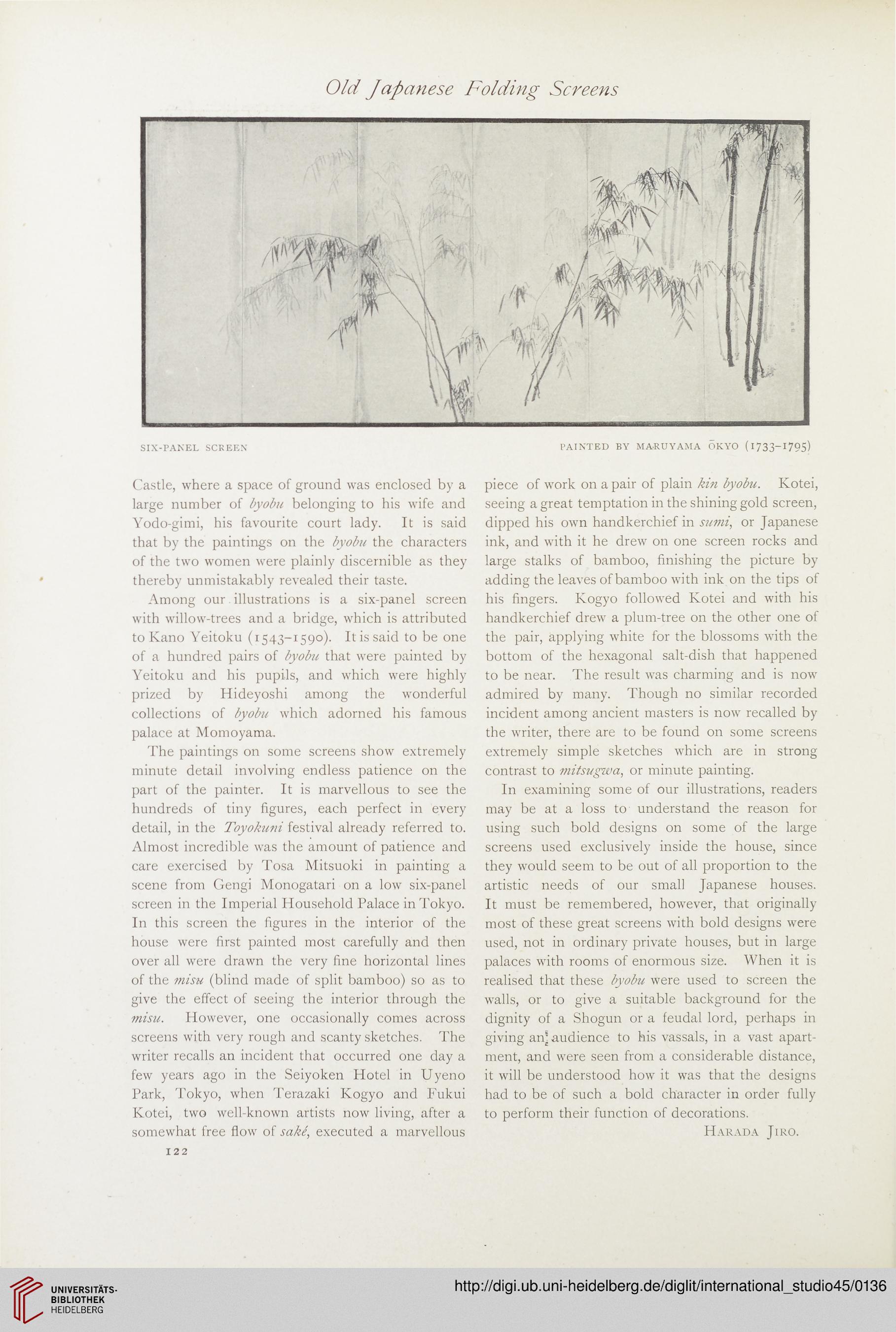

SIX-PANEL SCREEN

PAINTED BY MA-RUYAMA OKYO (1733-1795)

Castle, where a space of ground was enclosed by a

large number of byobu belonging to his wife and

Yodo-gimi, his favourite court lady. It is said

that by the paintings on the byobu the characters

of the two women were plainly discernible as they

thereby unmistakably revealed their taste.

Among our illustrations is a six-panel screen

with willow-trees and a bridge, which is attributed

to Kano Yeitoku (1543-1590). It is said to be one

of a hundred pairs of byobu that were painted by

Yeitoku and his pupils, and which were highly

prized by Hideyoshi among the wonderful

collections of byobu which adorned his famous

palace at Momoyama.

The paintings on some screens show extremely

minute detail involving endless patience on the

part of the painter. It is marvellous to see the

hundreds of tiny figures, each perfect in every

detail, in the Toyokuni festival already referred to.

Almost incredible was the amount of patience and

care exercised by Tosa Mitsuoki in painting a

scene from Gengi Monogatari on a low six-panel

screen in the Imperial Household Palace in Tokyo.

In this screen the figures in the interior of the

house were first painted most carefully and then

over all were drawn the very fine horizontal lines

of the misu (blind made of split bamboo) so as to

give the effect of seeing the interior through the

misu. However, one occasionally comes across

screens with very rough and scanty sketches. The

writer recalls an incident that occurred one day a

few years ago in the Seiyoken Hotel in Uyeno

Park, Tokyo, when Terazaki Kogyo and Fukui

Kotei, two well-known artists now living, after a

somewhat free flow of sake, executed a marvellous

piece of work on a pair of plain kin byobu. Kotei,

seeing a great temptation in the shining gold screen,

dipped his own handkerchief in sumi, or Japanese

ink, and with it he drew on one screen rocks and

large stalks of bamboo, finishing the picture by

adding the leaves of bamboo with ink on the tips of

his fingers. Kogyo followed Kotei and with his

handkerchief drew a plum-tree on the other one of

the pair, applying white for the blossoms with the

bottom of the hexagonal salt-dish that happened

to be near. The result was charming and is now

admired by many. Though no similar recorded

incident among ancient masters is now recalled by

the writer, there are to be found on some screens

extremely simple sketches which are in strong

contrast to mitsugwa, or minute painting.

In examining some of our illustrations, readers

may be at a loss to understand the reason for

using such bold designs on some of the large

screens used exclusively inside the house, since

they would seem to be out of all proportion to the

artistic needs of our small Japanese houses.

It must be remembered, however, that originally

most of these great screens with bold designs were

used, not in ordinary private houses, but in large

palaces with rooms of enormous size. When it is

realised that these byobu were used to screen the

walls, or to give a suitable background for the

dignity of a Shogun or a feudal lord, perhaps in

giving an® audience to his vassals, in a vast apart-

ment, and were seen from a considerable distance,

it will be understood how it was that the designs

had to be of such a bold character in order fully

to perform their function of decorations.

Harada Jiro.

122

SIX-PANEL SCREEN

PAINTED BY MA-RUYAMA OKYO (1733-1795)

Castle, where a space of ground was enclosed by a

large number of byobu belonging to his wife and

Yodo-gimi, his favourite court lady. It is said

that by the paintings on the byobu the characters

of the two women were plainly discernible as they

thereby unmistakably revealed their taste.

Among our illustrations is a six-panel screen

with willow-trees and a bridge, which is attributed

to Kano Yeitoku (1543-1590). It is said to be one

of a hundred pairs of byobu that were painted by

Yeitoku and his pupils, and which were highly

prized by Hideyoshi among the wonderful

collections of byobu which adorned his famous

palace at Momoyama.

The paintings on some screens show extremely

minute detail involving endless patience on the

part of the painter. It is marvellous to see the

hundreds of tiny figures, each perfect in every

detail, in the Toyokuni festival already referred to.

Almost incredible was the amount of patience and

care exercised by Tosa Mitsuoki in painting a

scene from Gengi Monogatari on a low six-panel

screen in the Imperial Household Palace in Tokyo.

In this screen the figures in the interior of the

house were first painted most carefully and then

over all were drawn the very fine horizontal lines

of the misu (blind made of split bamboo) so as to

give the effect of seeing the interior through the

misu. However, one occasionally comes across

screens with very rough and scanty sketches. The

writer recalls an incident that occurred one day a

few years ago in the Seiyoken Hotel in Uyeno

Park, Tokyo, when Terazaki Kogyo and Fukui

Kotei, two well-known artists now living, after a

somewhat free flow of sake, executed a marvellous

piece of work on a pair of plain kin byobu. Kotei,

seeing a great temptation in the shining gold screen,

dipped his own handkerchief in sumi, or Japanese

ink, and with it he drew on one screen rocks and

large stalks of bamboo, finishing the picture by

adding the leaves of bamboo with ink on the tips of

his fingers. Kogyo followed Kotei and with his

handkerchief drew a plum-tree on the other one of

the pair, applying white for the blossoms with the

bottom of the hexagonal salt-dish that happened

to be near. The result was charming and is now

admired by many. Though no similar recorded

incident among ancient masters is now recalled by

the writer, there are to be found on some screens

extremely simple sketches which are in strong

contrast to mitsugwa, or minute painting.

In examining some of our illustrations, readers

may be at a loss to understand the reason for

using such bold designs on some of the large

screens used exclusively inside the house, since

they would seem to be out of all proportion to the

artistic needs of our small Japanese houses.

It must be remembered, however, that originally

most of these great screens with bold designs were

used, not in ordinary private houses, but in large

palaces with rooms of enormous size. When it is

realised that these byobu were used to screen the

walls, or to give a suitable background for the

dignity of a Shogun or a feudal lord, perhaps in

giving an® audience to his vassals, in a vast apart-

ment, and were seen from a considerable distance,

it will be understood how it was that the designs

had to be of such a bold character in order fully

to perform their function of decorations.

Harada Jiro.

122