Dutch Pictures for South Africa

The Dominion has thus had the advantage of the

employment of one of the most discriminating

connoisseurs of our time, and the certainty that the

gallery will start with a basis of works of the

first order from which to extend its operations.

In referring to the collection as ideal we especially

have in mind the care which has been taken

to represent the four separate aspects of Dutch

painting in the seventeenth century, as respectively

shown in portraiture, landscape and still-life paint-

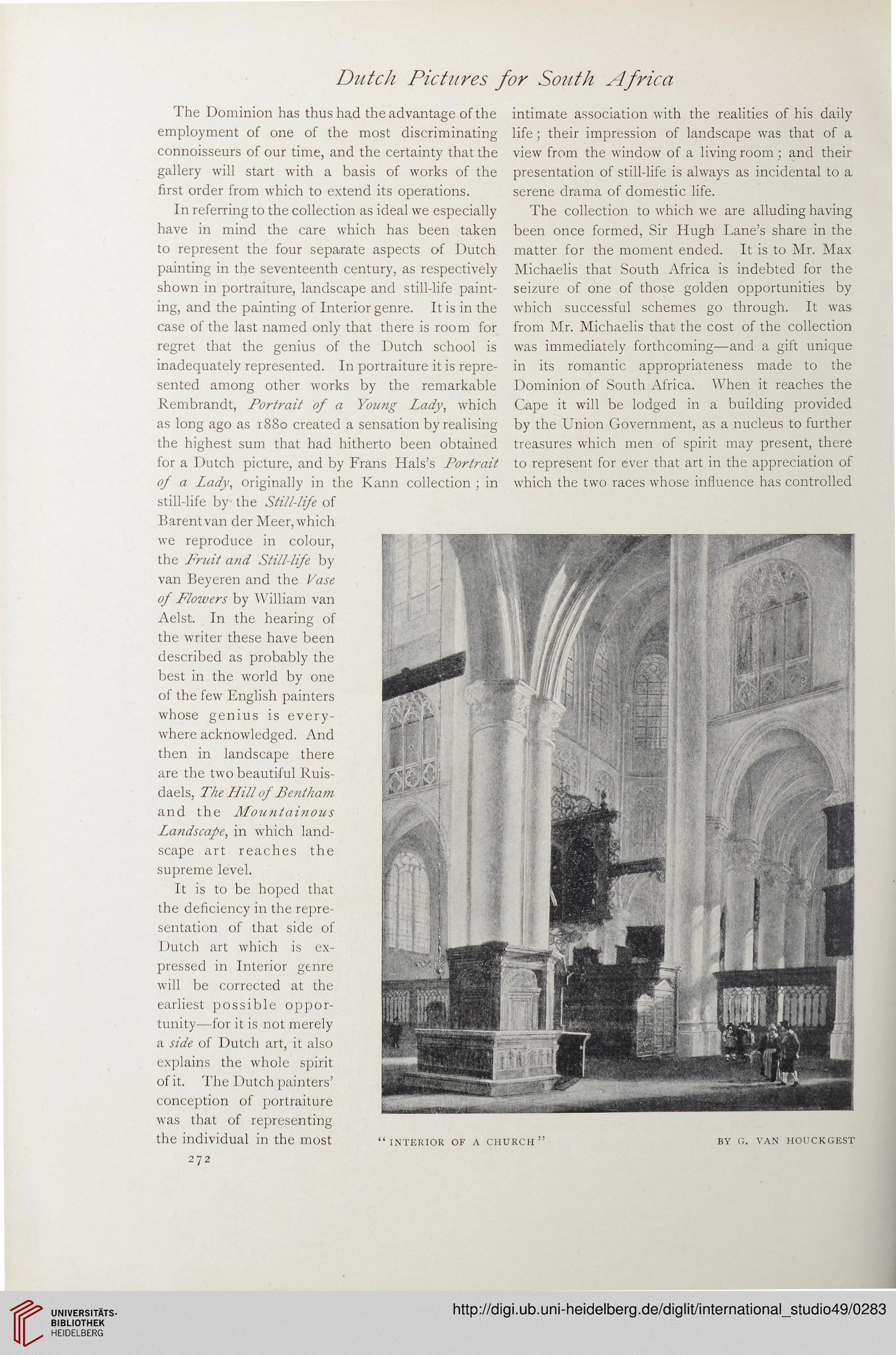

ing, and the painting of Interior genre. It is in the

case of the last named only that there is room for

regret that the genius of the Dutch school is

inadequately represented. In portraiture it is repre-

sented among other works by the remarkable

Rembrandt, Portrait of a Young Lady, which

as long ago as 1880 created a sensation by realising

the highest sum that had hitherto been obtained

for a Dutch picture, and by Frans Hals’s Portrait

of a Lady, originally in the Kann collection ; in

still-life by the Still-life of

Barent van der Meer, which

we reproduce in colour,

the Pruit and Still-life by

van Beyeren and the Vase

of Flowers by William van

Aelst. In the hearing of

the writer these have been

described as probably the

best in the world by one

of the few English painters

whose genius is every¬

where acknowledged. And

then in landscape there

are the two beautiful Ruis¬

daels, The Hill of Bentham

and the Mountainous

Landscape, in which land¬

scape art reaches the

supreme level.

It is to be hoped that

the deficiency in the repre¬

sentation of that side of

Dutch art which is ex¬

pressed in Interior genre

will be corrected at the

earliest possible oppor¬

tunity—for it is not merely

a side of Dutch art, it also

explains the whole spirit

of it. The Dutch painters’

conception of portraiture

was that of representing

the individual in the most

intimate association with the realities of his daily

life; their impression of landscape was that of a

view from the window of a living room; and their

presentation of still-life is always as incidental to a

serene drama of domestic life.

The collection to which we are alluding having

been once formed, Sir Hugh Lane’s share in the

matter for the moment ended. It is to Mr. Max

Michaelis that South Africa is indebted for the

seizure of one of those golden opportunities by

which successful schemes go through. It was

from Mr. Michaelis that the cost of the collection

was immediately forthcoming—and a gift unique

in its romantic appropriateness made to the

Dominion of South Africa. When it reaches the

Cape it will be lodged in a building provided

by the Union Government, as a nucleus to further

treasures which men of spirit may present, there

to represent for ever that art in the appreciation of

which the two races whose influence has controlled

“interior of a church”

BY G. VAN HOUCKGEST

272

The Dominion has thus had the advantage of the

employment of one of the most discriminating

connoisseurs of our time, and the certainty that the

gallery will start with a basis of works of the

first order from which to extend its operations.

In referring to the collection as ideal we especially

have in mind the care which has been taken

to represent the four separate aspects of Dutch

painting in the seventeenth century, as respectively

shown in portraiture, landscape and still-life paint-

ing, and the painting of Interior genre. It is in the

case of the last named only that there is room for

regret that the genius of the Dutch school is

inadequately represented. In portraiture it is repre-

sented among other works by the remarkable

Rembrandt, Portrait of a Young Lady, which

as long ago as 1880 created a sensation by realising

the highest sum that had hitherto been obtained

for a Dutch picture, and by Frans Hals’s Portrait

of a Lady, originally in the Kann collection ; in

still-life by the Still-life of

Barent van der Meer, which

we reproduce in colour,

the Pruit and Still-life by

van Beyeren and the Vase

of Flowers by William van

Aelst. In the hearing of

the writer these have been

described as probably the

best in the world by one

of the few English painters

whose genius is every¬

where acknowledged. And

then in landscape there

are the two beautiful Ruis¬

daels, The Hill of Bentham

and the Mountainous

Landscape, in which land¬

scape art reaches the

supreme level.

It is to be hoped that

the deficiency in the repre¬

sentation of that side of

Dutch art which is ex¬

pressed in Interior genre

will be corrected at the

earliest possible oppor¬

tunity—for it is not merely

a side of Dutch art, it also

explains the whole spirit

of it. The Dutch painters’

conception of portraiture

was that of representing

the individual in the most

intimate association with the realities of his daily

life; their impression of landscape was that of a

view from the window of a living room; and their

presentation of still-life is always as incidental to a

serene drama of domestic life.

The collection to which we are alluding having

been once formed, Sir Hugh Lane’s share in the

matter for the moment ended. It is to Mr. Max

Michaelis that South Africa is indebted for the

seizure of one of those golden opportunities by

which successful schemes go through. It was

from Mr. Michaelis that the cost of the collection

was immediately forthcoming—and a gift unique

in its romantic appropriateness made to the

Dominion of South Africa. When it reaches the

Cape it will be lodged in a building provided

by the Union Government, as a nucleus to further

treasures which men of spirit may present, there

to represent for ever that art in the appreciation of

which the two races whose influence has controlled

“interior of a church”

BY G. VAN HOUCKGEST

272