Wood-Engraving for Colour

though he follows in principle the technique of the

Japanese woodcutters and printers, he seems never

to tire of experiment in the development of his own

practice. He thinks his methods out for himself.

Unlike his fellow-workers, he prefers the wood of

the Kauri pine from New Zealand to the customary

cherry or pear, than which he finds it is more

available. It can be got of any width up to about

four or five feet, and though it may not be good

for hundreds of impressions, as the harder woods

are, it can be depended upon for fifty. It is softer

for the inexperienced cutter to work, while for the

expert it it as good as cherry ; sycamore, by the way,

being very hard to prepare, since the grain keeps

coming up. Another matter in which Mr. Giles

goes his own way is in the use of starch-paste

instead of rice paste for mixing his powder-colours.

Like most enthusiasts, Mr. Giles is always ready

to talk about his craft, if he finds an attentive and

interested listener—and certainly, if one wants to

learn something of the artistic colour-printer’s

methods, it is well to listen to Mr. Giles. As to

colour-schemes, for instance, he will tell you that

“simplicity of treatment should always be one’s

aim, achieved, not with any archaic affectation,

but as a pleasure-giving

inspiration, to awaken

latent memories in others.

The day’s mood should

suggest the colours. Do

not the rosy tints of a

summer’s noon deepen

into purple at eventide,

to darken into the ulti¬

mate violet of night?

Does not the cobalt of

day gradate and quiver

into ultramarine, to deepen

again into the watery depth

of the sapphire night ?

One selects one’s colours,

therefore, according to

these personal sensations

of vision, tempering the

choice with the limita¬

tions of the pigment. Per¬

haps I am thinking too

strongly of the atmo¬

spheric unity of nature,

dominated always by one

main source of light.

There is another way of

seeing colour, namely,

tuning into harmony dis

cordant hues by an harmonic balance and com-

pensation, making a colour-creation of design.”

Again, if you ask Mr. Giles as to the number of

printings from wood-blocks required in an attempt

to render the fulness of nature, he will tell you

that these usually resolve themselves into about

thirty or so, though the blocks from which these

thirty printings are done number only about eight,

that is, from plank-boards cut on either side,

making the eight board-faces or blocks. Each of

these eight board-faces may contain as many or

as few colour-shapes as the nature of the design

demands. In printing, these colour-shapes are

conceived as colour-pattern, in the same spirit as

in intarsia design, with this addition, that each

colour-shape requires especial attention. If print-

ing-shapes could be arbitrarily selected in number,

four would be about the limit for each board; but

in practice this is never the case, for one desired

colour-shape is usually fouled by another. The

intended rhythm of order being destroyed, the

colour-shapes are cut on the boards in the order

they will best fit, so as to save endless blocks. In

laying water-colour washes on these shapes prior

to printing, it will be found that before the last

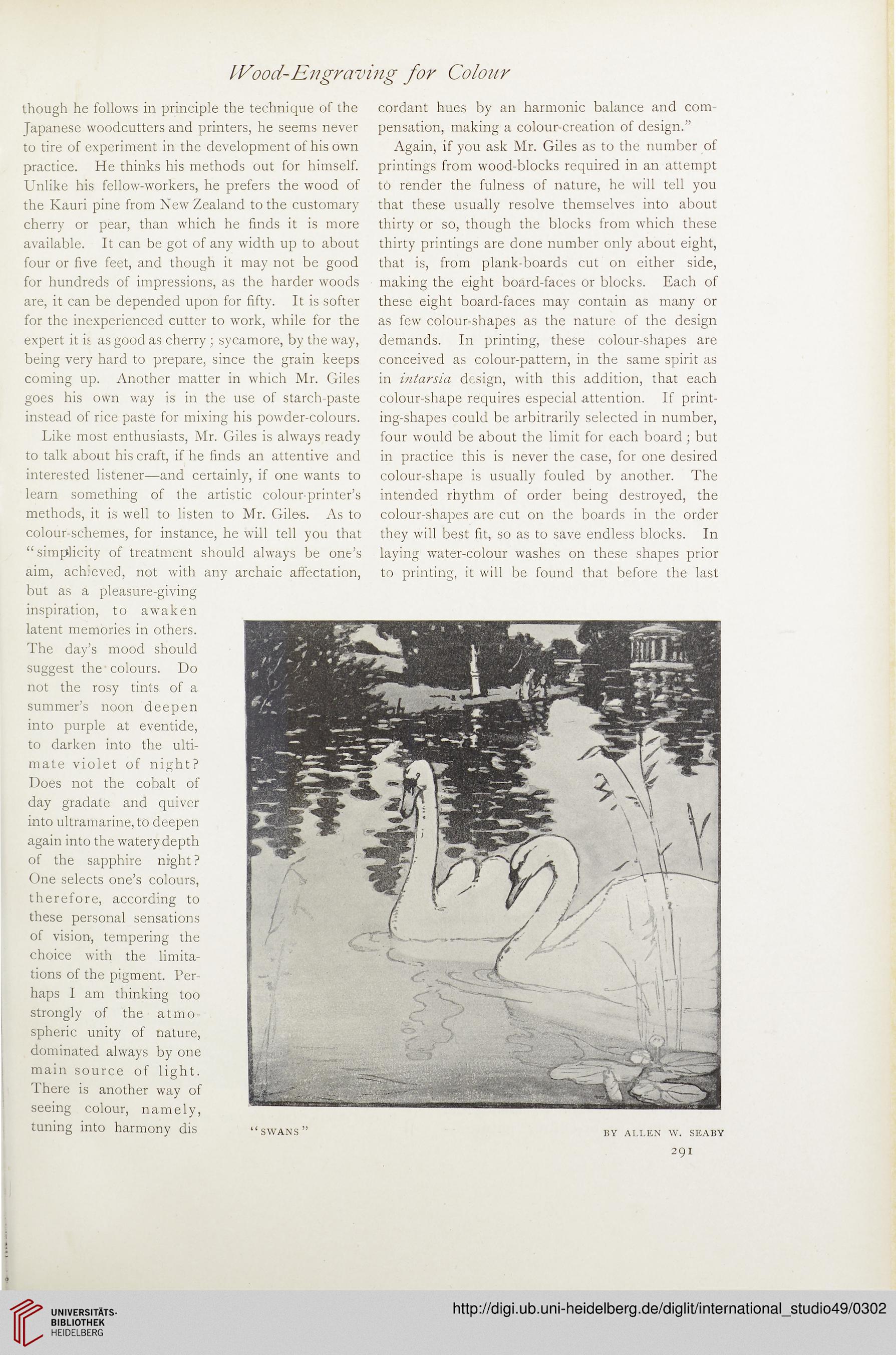

BY ALLEN W. SEABY

29I

though he follows in principle the technique of the

Japanese woodcutters and printers, he seems never

to tire of experiment in the development of his own

practice. He thinks his methods out for himself.

Unlike his fellow-workers, he prefers the wood of

the Kauri pine from New Zealand to the customary

cherry or pear, than which he finds it is more

available. It can be got of any width up to about

four or five feet, and though it may not be good

for hundreds of impressions, as the harder woods

are, it can be depended upon for fifty. It is softer

for the inexperienced cutter to work, while for the

expert it it as good as cherry ; sycamore, by the way,

being very hard to prepare, since the grain keeps

coming up. Another matter in which Mr. Giles

goes his own way is in the use of starch-paste

instead of rice paste for mixing his powder-colours.

Like most enthusiasts, Mr. Giles is always ready

to talk about his craft, if he finds an attentive and

interested listener—and certainly, if one wants to

learn something of the artistic colour-printer’s

methods, it is well to listen to Mr. Giles. As to

colour-schemes, for instance, he will tell you that

“simplicity of treatment should always be one’s

aim, achieved, not with any archaic affectation,

but as a pleasure-giving

inspiration, to awaken

latent memories in others.

The day’s mood should

suggest the colours. Do

not the rosy tints of a

summer’s noon deepen

into purple at eventide,

to darken into the ulti¬

mate violet of night?

Does not the cobalt of

day gradate and quiver

into ultramarine, to deepen

again into the watery depth

of the sapphire night ?

One selects one’s colours,

therefore, according to

these personal sensations

of vision, tempering the

choice with the limita¬

tions of the pigment. Per¬

haps I am thinking too

strongly of the atmo¬

spheric unity of nature,

dominated always by one

main source of light.

There is another way of

seeing colour, namely,

tuning into harmony dis

cordant hues by an harmonic balance and com-

pensation, making a colour-creation of design.”

Again, if you ask Mr. Giles as to the number of

printings from wood-blocks required in an attempt

to render the fulness of nature, he will tell you

that these usually resolve themselves into about

thirty or so, though the blocks from which these

thirty printings are done number only about eight,

that is, from plank-boards cut on either side,

making the eight board-faces or blocks. Each of

these eight board-faces may contain as many or

as few colour-shapes as the nature of the design

demands. In printing, these colour-shapes are

conceived as colour-pattern, in the same spirit as

in intarsia design, with this addition, that each

colour-shape requires especial attention. If print-

ing-shapes could be arbitrarily selected in number,

four would be about the limit for each board; but

in practice this is never the case, for one desired

colour-shape is usually fouled by another. The

intended rhythm of order being destroyed, the

colour-shapes are cut on the boards in the order

they will best fit, so as to save endless blocks. In

laying water-colour washes on these shapes prior

to printing, it will be found that before the last

BY ALLEN W. SEABY

29I