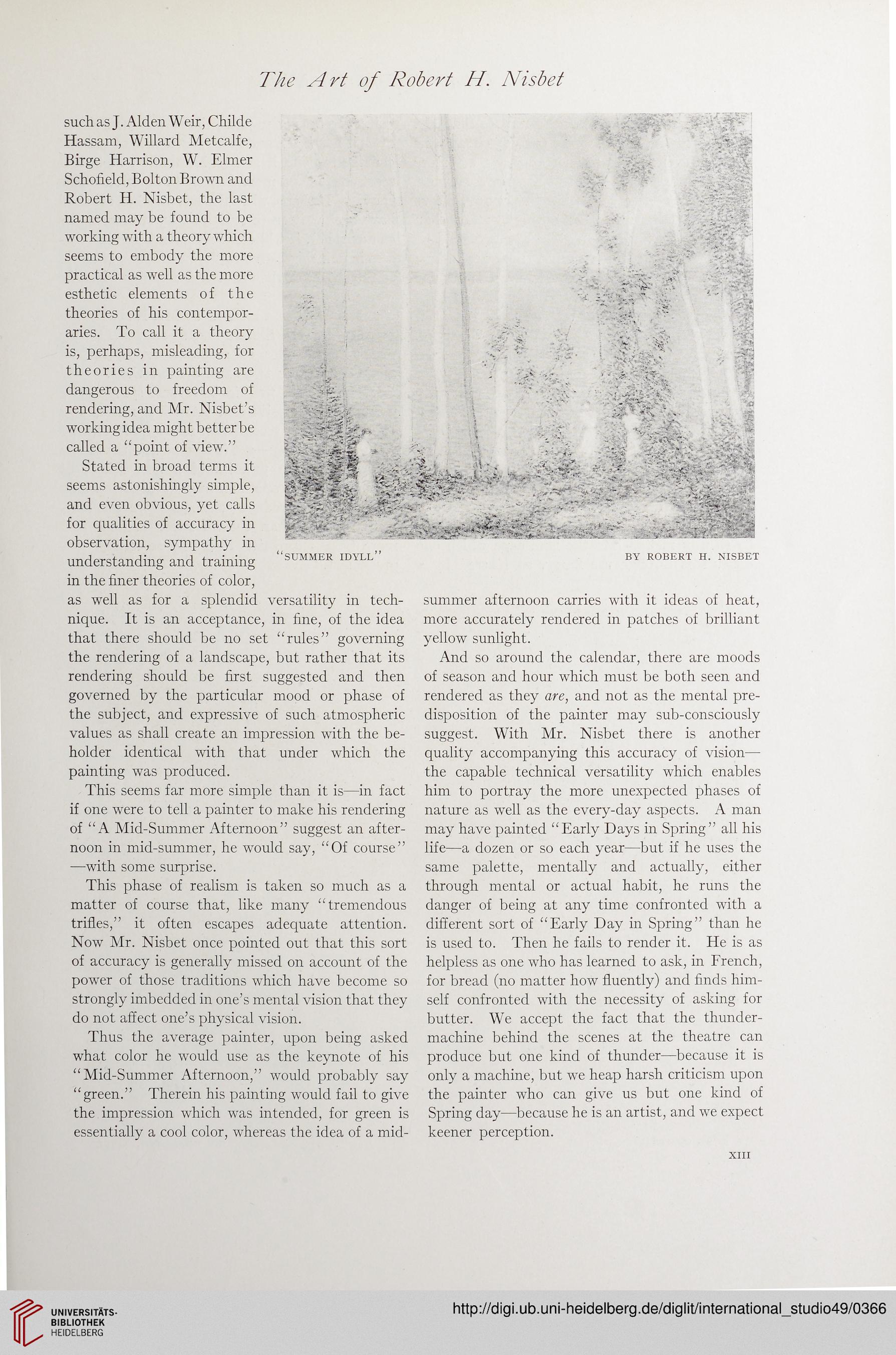

The Art of Robert H. Nisbet

such as J. Alden Weir, Childe

Hassam, Willard Metcalfe,

Birge Harrison, W. Elmer

Schofield, Bolton Brown and

Robert H. Nisbet, the last

named may be found to be

working with a theory which

seems to embody the more

practical as well as the more

esthetic elements of the

theories of his contempor-

aries. To call it a theory

is, perhaps, misleading, for

theories in painting are

dangerous to freedom of

rendering, and Mr. Nisbet’s

working idea might better be

called a “point of view.”

Stated in broad terms it

seems astonishingly simple,

and even obvious, yet calls

for qualities of accuracy in

observation, sympathy in

understanding and training

in the finer theories of color,

as well as for a splendid versatility in tech-

nique. It is an acceptance, in fine, of the idea

that there should be no set “rules” governing

the rendering of a landscape, but rather that its

rendering should be first suggested and then

governed by the particular mood or phase of

the subject, and expressive of such atmospheric

values as shall create an impression with the be-

holder identical with that under which the

painting was produced.

This seems far more simple than it is—in fact

if one were to tell a painter to make his rendering

of “A Mid-Summer Afternoon” suggest an after-

noon in mid-summer, he would say, “Of course”

—with some surprise.

This phase of realism is taken so much as a

matter of course that, like many “tremendous

trifles,” it often escapes adequate attention.

Now Mr. Nisbet once pointed out that this sort

of accuracy is generally missed on account of the

power of those traditions which have become so

strongly imbedded in one’s mental vision that they

do not affect one’s physical vision.

Thus the average painter, upon being asked

what color he would use as the keynote of his

“Mid-Summer Afternoon,” would probably say

“green.” Therein his painting would fail to give

the impression which was intended, for green is

essentially a cool color, whereas the idea of a mid-

summer afternoon carries with it ideas of heat,

more accurately rendered in patches of brilliant

yellow sunlight.

And so around the calendar, there are moods

of season and hour which must be both seen and

rendered as they are, and not as the mental pre-

disposition of the painter may sub-consciously

suggest. With Mr. Nisbet there is another

quality accompanying this accuracy of vision—

the capable technical versatility which enables

him to portray the more unexpected phases of

nature as well as the every-day aspects. A man

may have painted “Early Days in Spring” all his

life—a dozen or so each year—but if he uses the

same palette, mentally and actually, either

through mental or actual habit, he runs the

danger of being at any time confronted with a

different sort of “Early Day in Spring” than he

is used to. Then he fails to render it. He is as

helpless as one who has learned to ask, in French,

for bread (no matter how fluently) and finds him-

self confronted with the necessity of asking for

butter. We accept the fact that the thunder-

machine behind the scenes at the theatre can

produce but one kind of thunder—because it is

only a machine, but we heap harsh criticism upon

the painter who can give us but one kind of

Spring day—because he is an artist, and we expect

keener perception.

XIII

such as J. Alden Weir, Childe

Hassam, Willard Metcalfe,

Birge Harrison, W. Elmer

Schofield, Bolton Brown and

Robert H. Nisbet, the last

named may be found to be

working with a theory which

seems to embody the more

practical as well as the more

esthetic elements of the

theories of his contempor-

aries. To call it a theory

is, perhaps, misleading, for

theories in painting are

dangerous to freedom of

rendering, and Mr. Nisbet’s

working idea might better be

called a “point of view.”

Stated in broad terms it

seems astonishingly simple,

and even obvious, yet calls

for qualities of accuracy in

observation, sympathy in

understanding and training

in the finer theories of color,

as well as for a splendid versatility in tech-

nique. It is an acceptance, in fine, of the idea

that there should be no set “rules” governing

the rendering of a landscape, but rather that its

rendering should be first suggested and then

governed by the particular mood or phase of

the subject, and expressive of such atmospheric

values as shall create an impression with the be-

holder identical with that under which the

painting was produced.

This seems far more simple than it is—in fact

if one were to tell a painter to make his rendering

of “A Mid-Summer Afternoon” suggest an after-

noon in mid-summer, he would say, “Of course”

—with some surprise.

This phase of realism is taken so much as a

matter of course that, like many “tremendous

trifles,” it often escapes adequate attention.

Now Mr. Nisbet once pointed out that this sort

of accuracy is generally missed on account of the

power of those traditions which have become so

strongly imbedded in one’s mental vision that they

do not affect one’s physical vision.

Thus the average painter, upon being asked

what color he would use as the keynote of his

“Mid-Summer Afternoon,” would probably say

“green.” Therein his painting would fail to give

the impression which was intended, for green is

essentially a cool color, whereas the idea of a mid-

summer afternoon carries with it ideas of heat,

more accurately rendered in patches of brilliant

yellow sunlight.

And so around the calendar, there are moods

of season and hour which must be both seen and

rendered as they are, and not as the mental pre-

disposition of the painter may sub-consciously

suggest. With Mr. Nisbet there is another

quality accompanying this accuracy of vision—

the capable technical versatility which enables

him to portray the more unexpected phases of

nature as well as the every-day aspects. A man

may have painted “Early Days in Spring” all his

life—a dozen or so each year—but if he uses the

same palette, mentally and actually, either

through mental or actual habit, he runs the

danger of being at any time confronted with a

different sort of “Early Day in Spring” than he

is used to. Then he fails to render it. He is as

helpless as one who has learned to ask, in French,

for bread (no matter how fluently) and finds him-

self confronted with the necessity of asking for

butter. We accept the fact that the thunder-

machine behind the scenes at the theatre can

produce but one kind of thunder—because it is

only a machine, but we heap harsh criticism upon

the painter who can give us but one kind of

Spring day—because he is an artist, and we expect

keener perception.

XIII