The French Institute and “American' Art

Metropolitan. France does not pretend to mon-

opolize art; it does not pretend to know all there

is to be known on the subject, but what it does

know it is willing to pass on to others. Some of

the best architects of this country owe what they

know of their art to the teaching received at the

Beaux-Arts in Paris. The planting of the French

Institute on American soil is only an extension of

that general principle of helpfulness to others

which has ever guided the French world of art.

Instead of arousing distrust and suspicion it should

arouse enthusiasm and gratitude.

Thanks to the generosity of the French nation,

the American artist or artisan feeling a leaning for

the French manner of seeing and portraying, will

have an opportunity

to study the doctrine

of art as taught to and

applied by French

artists. Here is a ref-

erence library open to

them, in which not¬

able precedents are

pictured giving ad¬

vice as much on what

to avoid as on what

to imitate.

A

NOTE ON

ALBERT

BESNARD

The collection of

Besnard’s works to

be placed upon ex¬

hibition here is varied enough in character to

permit an intelligent verdict being rendered on

the ensemble of that painter’s art. Not only

will he be shown as a portraitist and decorator,

but as an etcher and engraver as well.

The dazzling fire and flame effects which first

brought him into public notice twenty-five years

ago are present in one at least of the paintings to

be shown, the portrait of Princess Mathilde, but

the sensational canvases of Rejane and Mme.

Roger Jourdain, in which this incandescence of

color finds its fullest expression, are missing from

the collection.

The editor of the Studio has thought that the

readers of the magazine would be interested in a

reproduction of these two famous portraits and

in a short article touching upon a phase of

Besnard’s work not sufficiently emphasized in

the coming exhibit, and that is, his illumination

effects.

Since Besnard’s fame will probably rest upon

his magical treatment of conflicting lamp light

and moonlight and the play of these upon satin

and silk, the article in question may prove of some

interest.

One of the characteristics of Besnard’s work

which the forthcoming exhibition will not show, is

his evolution from the pre-Raphaelite school into

the impressionist and from the impressionist into

the academic or if not quite the academic, at least

the naturalist.

As his mode of expression changed, critics found

new prototypes for his paintings. In his youthful

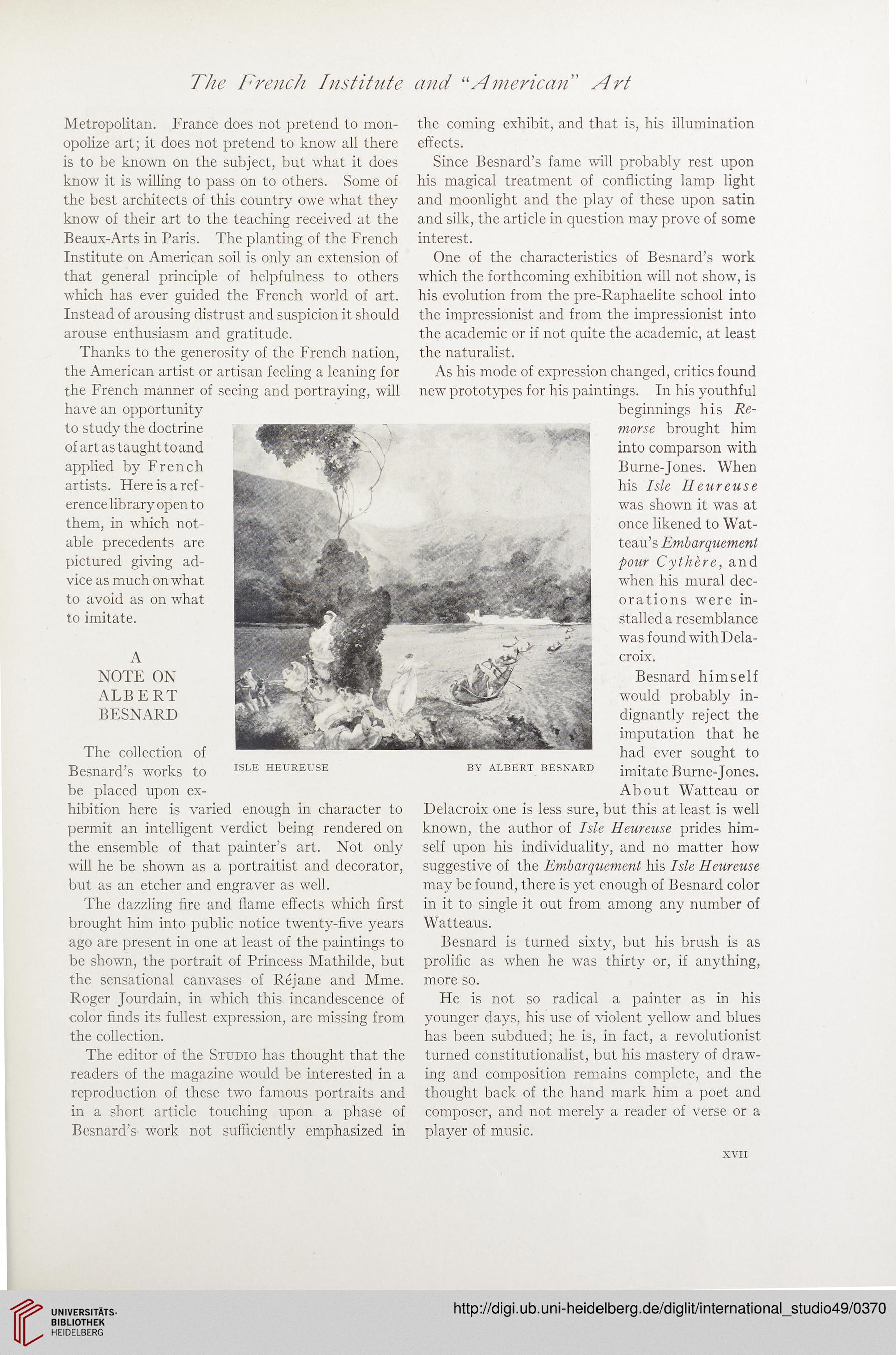

beginnings his Re-

morse brought him

into comparson with

Burne-Jones. When

his Isle Heureuse

was shown it was at

once likened to Wat-

teau’s Embarquement

pour Cythere, and

when his mural dec-

orations were in-

stalled a resemblance

was found with Dela-

croix.

Besnard himself

would probably in-

dignantly reject the

imputation that he

had ever sought to

imitate Burne-Jones.

About Watteau or

Delacroix one is less sure, but this at least is well

known, the author of Isle IIeureuse prides him-

self upon his individuality, and no matter how

suggestive of the Embarquement his Isle Heureuse

may be found, there is yet enough of Besnard color

in it to single it out from among any number of

Watteaus.

Besnard is turned sixty, but his brush is as

prolific as when he was thirty or, if anything,

more so.

He is not so radical a painter as in his

younger days, his use of violent yellow and blues

has been subdued; he is, in fact, a revolutionist

turned constitutionalist, but his mastery of draw-

ing and composition remains complete, and the

thought back of the hand mark him a poet and

composer, and not merely a reader of verse or a

player of music.

ISLE HEUREUSE BY ALBERT BESNARD

BY ALBERT BESNARD

XVII

Metropolitan. France does not pretend to mon-

opolize art; it does not pretend to know all there

is to be known on the subject, but what it does

know it is willing to pass on to others. Some of

the best architects of this country owe what they

know of their art to the teaching received at the

Beaux-Arts in Paris. The planting of the French

Institute on American soil is only an extension of

that general principle of helpfulness to others

which has ever guided the French world of art.

Instead of arousing distrust and suspicion it should

arouse enthusiasm and gratitude.

Thanks to the generosity of the French nation,

the American artist or artisan feeling a leaning for

the French manner of seeing and portraying, will

have an opportunity

to study the doctrine

of art as taught to and

applied by French

artists. Here is a ref-

erence library open to

them, in which not¬

able precedents are

pictured giving ad¬

vice as much on what

to avoid as on what

to imitate.

A

NOTE ON

ALBERT

BESNARD

The collection of

Besnard’s works to

be placed upon ex¬

hibition here is varied enough in character to

permit an intelligent verdict being rendered on

the ensemble of that painter’s art. Not only

will he be shown as a portraitist and decorator,

but as an etcher and engraver as well.

The dazzling fire and flame effects which first

brought him into public notice twenty-five years

ago are present in one at least of the paintings to

be shown, the portrait of Princess Mathilde, but

the sensational canvases of Rejane and Mme.

Roger Jourdain, in which this incandescence of

color finds its fullest expression, are missing from

the collection.

The editor of the Studio has thought that the

readers of the magazine would be interested in a

reproduction of these two famous portraits and

in a short article touching upon a phase of

Besnard’s work not sufficiently emphasized in

the coming exhibit, and that is, his illumination

effects.

Since Besnard’s fame will probably rest upon

his magical treatment of conflicting lamp light

and moonlight and the play of these upon satin

and silk, the article in question may prove of some

interest.

One of the characteristics of Besnard’s work

which the forthcoming exhibition will not show, is

his evolution from the pre-Raphaelite school into

the impressionist and from the impressionist into

the academic or if not quite the academic, at least

the naturalist.

As his mode of expression changed, critics found

new prototypes for his paintings. In his youthful

beginnings his Re-

morse brought him

into comparson with

Burne-Jones. When

his Isle Heureuse

was shown it was at

once likened to Wat-

teau’s Embarquement

pour Cythere, and

when his mural dec-

orations were in-

stalled a resemblance

was found with Dela-

croix.

Besnard himself

would probably in-

dignantly reject the

imputation that he

had ever sought to

imitate Burne-Jones.

About Watteau or

Delacroix one is less sure, but this at least is well

known, the author of Isle IIeureuse prides him-

self upon his individuality, and no matter how

suggestive of the Embarquement his Isle Heureuse

may be found, there is yet enough of Besnard color

in it to single it out from among any number of

Watteaus.

Besnard is turned sixty, but his brush is as

prolific as when he was thirty or, if anything,

more so.

He is not so radical a painter as in his

younger days, his use of violent yellow and blues

has been subdued; he is, in fact, a revolutionist

turned constitutionalist, but his mastery of draw-

ing and composition remains complete, and the

thought back of the hand mark him a poet and

composer, and not merely a reader of verse or a

player of music.

ISLE HEUREUSE BY ALBERT BESNARD

BY ALBERT BESNARD

XVII