Evolution not Revolution in Art

little by little stooped to a sort of debased illusion-

ism, and in order to extricate ourselves from the

stupidity and stagnation of such a predicament

we have gone back to the fountain heads of primi-

tive art as they may be found in Hindu-China or

Yucatan, on the plains of Mongolia, in the basin of

the Nile, or among the shimmering islands of the

Polynesian archipelago.

Distinctly less revolutionary than reactionary,

the modernists have merely reverted to an earlier

type of art, and in doing so it was inevitably to the

East that they were forced to turn. The present

movement, of which we hear so much, possibly too

much, represents more than anything the subtle

ascendancy of Orient over Occident. The first

premonition of this impending triumph was appar-

ent as far back as the early ’sixties of the past cen-

tury, when a certain Mme. Desoye opened in Paris

a modest shop where she sold Japanese prints,

pottery, screens and the like, and succeeded in

attracting the notice of Bracquemond, Louis

Gonse, the de Goncourts and other discerning

spirits. Scattered quite by chance, the seed soon

bore fruit in more than one quarter. Though

Whistler paid his tribute in explicit fashion, it was

Manet who, inspired by the Spaniards and freed

from scholastic influences by the sturdy example

of Courbet, first seized upon the essentials of

Eastern art—-the simplicity of outline, the juxta-

position of pure color tones, and the substitution

for elaborate modelling of flat surfaces without the

use of shadow. The virtual precursor of the

Impressionists, on the one hand, Manet may also

be ranked as the pioneer Expressionist, for it was

indisputably from him that Cezanne received hints

of that structural and chromatic integrity which

became the keynote of his method and the corner-

stone of subsequent achievement.

We shall not pause to trace this movement in all

it manifold ramifications. The significant point

is that one after another the succeeding men threw

over the cumbersome counsels of the schools and

went straight to the heart of things. You will find

Cezanne, ever sane and balanced, calmly extract-

ing from nature and natural

appearances their organic

unity. You will see Gau-

guin, the so-called barbarian,

depicting life and scene in

far-off Tahiti with a subdued

splendor of tone and stateli-

ness of pose that hark back

through Degas, Ingres, and

Prudhon to the ordered spa-

ciousness of Classic times.

And, lastly, you will be con-

fronted in Van Gogh with a

fusion of Gothic fervor and

sheer dynamic force which

gives his tortured landscapes

something of the eternal

throb of creative energy.

Each, after his own particu-

lar fashion, strove to free

eye and mind alike from the

meticulous elaboration of

academic practice and from

the popular fetish of purely

descriptive presentation.

Each sought not the sub-

stance but the spirit, and

that is why together they

constitute the initiators of

latter-day painting.

Once the importance of

the lesson taught by these

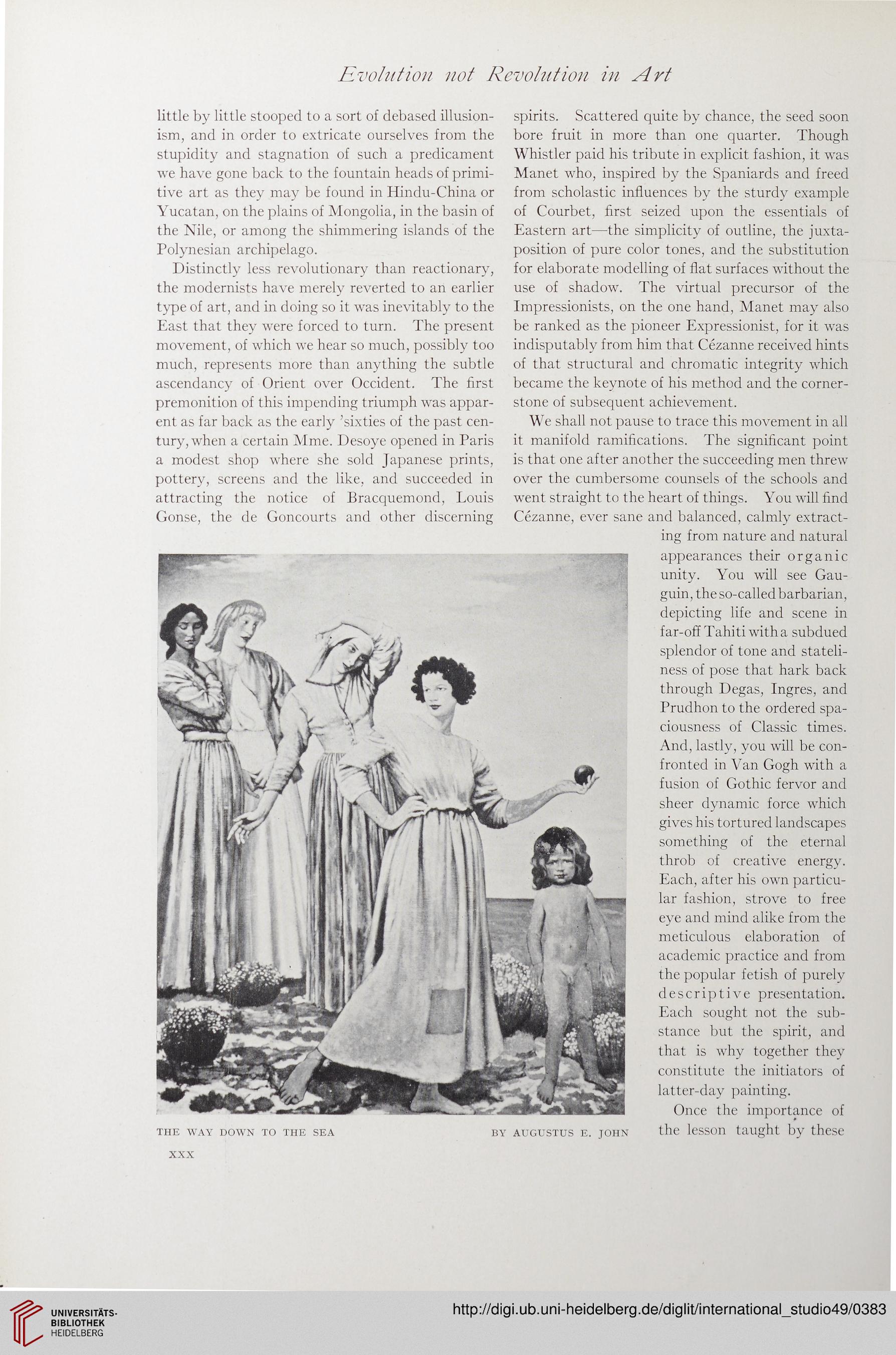

THE WAY DOWN TO THE SEA

BY AUGUSTUS E. JOHN

XXX

little by little stooped to a sort of debased illusion-

ism, and in order to extricate ourselves from the

stupidity and stagnation of such a predicament

we have gone back to the fountain heads of primi-

tive art as they may be found in Hindu-China or

Yucatan, on the plains of Mongolia, in the basin of

the Nile, or among the shimmering islands of the

Polynesian archipelago.

Distinctly less revolutionary than reactionary,

the modernists have merely reverted to an earlier

type of art, and in doing so it was inevitably to the

East that they were forced to turn. The present

movement, of which we hear so much, possibly too

much, represents more than anything the subtle

ascendancy of Orient over Occident. The first

premonition of this impending triumph was appar-

ent as far back as the early ’sixties of the past cen-

tury, when a certain Mme. Desoye opened in Paris

a modest shop where she sold Japanese prints,

pottery, screens and the like, and succeeded in

attracting the notice of Bracquemond, Louis

Gonse, the de Goncourts and other discerning

spirits. Scattered quite by chance, the seed soon

bore fruit in more than one quarter. Though

Whistler paid his tribute in explicit fashion, it was

Manet who, inspired by the Spaniards and freed

from scholastic influences by the sturdy example

of Courbet, first seized upon the essentials of

Eastern art—-the simplicity of outline, the juxta-

position of pure color tones, and the substitution

for elaborate modelling of flat surfaces without the

use of shadow. The virtual precursor of the

Impressionists, on the one hand, Manet may also

be ranked as the pioneer Expressionist, for it was

indisputably from him that Cezanne received hints

of that structural and chromatic integrity which

became the keynote of his method and the corner-

stone of subsequent achievement.

We shall not pause to trace this movement in all

it manifold ramifications. The significant point

is that one after another the succeeding men threw

over the cumbersome counsels of the schools and

went straight to the heart of things. You will find

Cezanne, ever sane and balanced, calmly extract-

ing from nature and natural

appearances their organic

unity. You will see Gau-

guin, the so-called barbarian,

depicting life and scene in

far-off Tahiti with a subdued

splendor of tone and stateli-

ness of pose that hark back

through Degas, Ingres, and

Prudhon to the ordered spa-

ciousness of Classic times.

And, lastly, you will be con-

fronted in Van Gogh with a

fusion of Gothic fervor and

sheer dynamic force which

gives his tortured landscapes

something of the eternal

throb of creative energy.

Each, after his own particu-

lar fashion, strove to free

eye and mind alike from the

meticulous elaboration of

academic practice and from

the popular fetish of purely

descriptive presentation.

Each sought not the sub-

stance but the spirit, and

that is why together they

constitute the initiators of

latter-day painting.

Once the importance of

the lesson taught by these

THE WAY DOWN TO THE SEA

BY AUGUSTUS E. JOHN

XXX