Evolution not Revolution in Art

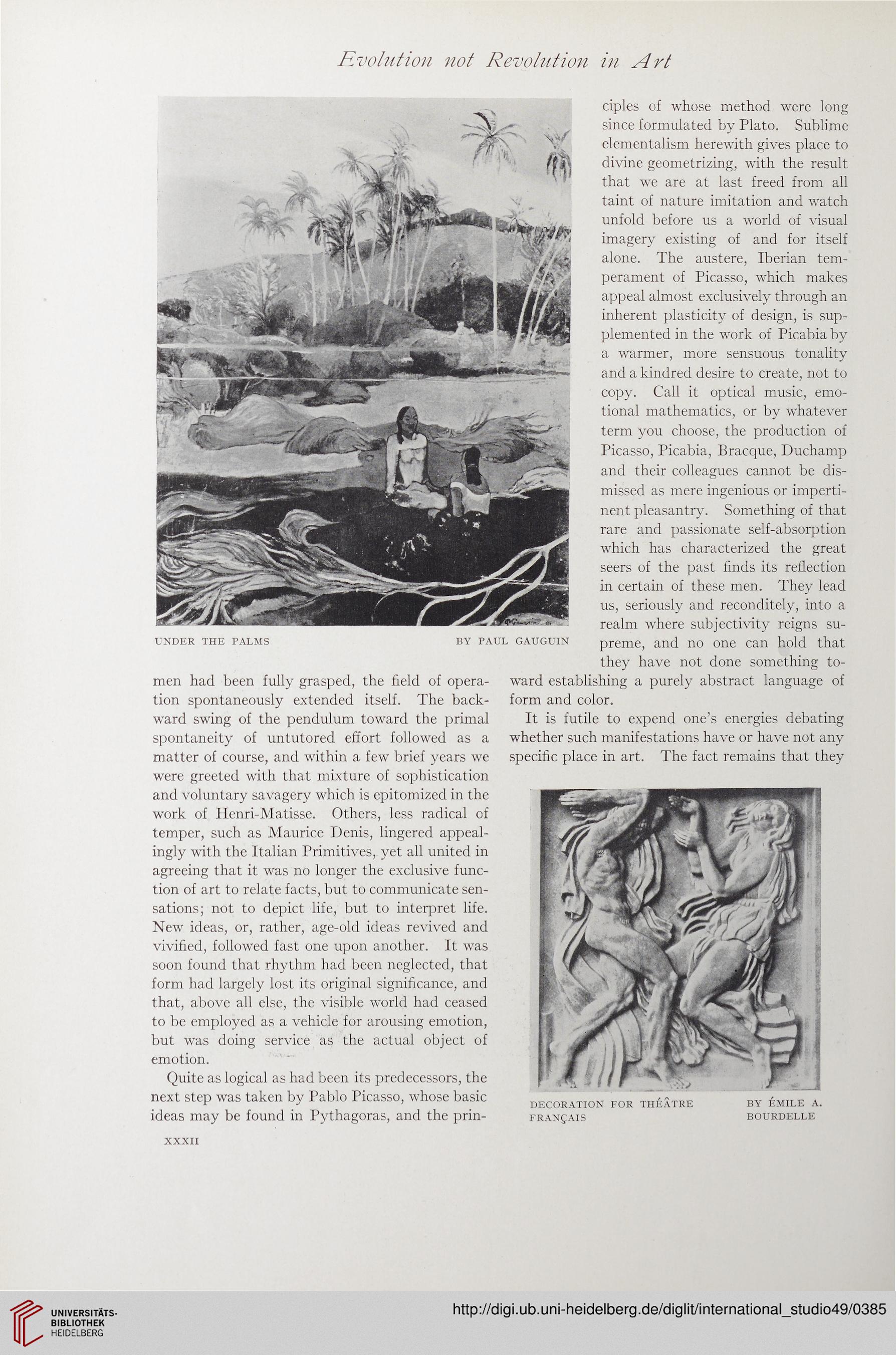

BY PAUL GAUGUIN

UNDER THE PALMS

men had been fully grasped, the field of opera-

tion spontaneously extended itself. The back-

ward swing of the pendulum toward the primal

spontaneity of untutored effort followed as a

matter of course, and within a few brief years we

were greeted with that mixture of sophistication

and voluntary savagery which is epitomized in the

work of Henri-Matisse. Others, less radical of

temper, such as Maurice Denis, lingered appeal-

ingly with the Italian Primitives, yet all united in

agreeing that it was no longer the exclusive func-

tion of art to relate facts, but to communicate sen-

sations; not to depict life, but to interpret life.

New ideas, or, rather, age-old ideas revived and

vivified, followed fast one upon another. It was

soon found that rhythm had been neglected, that

form had largely lost its original significance, and

that, above all else, the visible world had ceased

to be employed as a vehicle for arousing emotion,

but was doing service as the actual object of

emotion.

Quite as logical as had been its predecessors, the

next step was taken by Pablo Picasso, whose basic

ideas may be found in Pythagoras, and the prin-

ciples of whose method were long

since formulated by Plato. Sublime

elementalism herewith gives place to

divine geometrizing, with the result

that we are at last freed from all

taint of nature imitation and watch

unfold before us a world of visual

imagery existing of and for itself

alone. The austere, Iberian tem-

perament of Picasso, which makes

appeal almost exclusively through an

inherent plasticity of design, is sup-

plemented in the work of Picabia by

a warmer, more sensuous tonality

and a kindred desire to create, not to

copy. Call it optical music, emo-

tional mathematics, or by whatever

term you choose, the production of

Picasso, Picabia, Bracque, Duchamp

and their colleagues cannot be dis-

missed as mere ingenious or imperti-

nent pleasantry. Something of that

rare and passionate self-absorption

which has characterized the great

seers of the past finds its reflection

in certain of these men. They lead

us, seriously and reconditely, into a

realm where subjectivity reigns su-

preme, and no one can hold that

they have not done something to¬

ward establishing a purely abstract language of

form and color.

It is futile to expend one’s energies debating

whether such manifestations have or have not any

specific place in art. The fact remains that they

DECORATION FOR THEATRE BY EMILE A.

FRANQAIS BOURDELLE

XXXII

BY PAUL GAUGUIN

UNDER THE PALMS

men had been fully grasped, the field of opera-

tion spontaneously extended itself. The back-

ward swing of the pendulum toward the primal

spontaneity of untutored effort followed as a

matter of course, and within a few brief years we

were greeted with that mixture of sophistication

and voluntary savagery which is epitomized in the

work of Henri-Matisse. Others, less radical of

temper, such as Maurice Denis, lingered appeal-

ingly with the Italian Primitives, yet all united in

agreeing that it was no longer the exclusive func-

tion of art to relate facts, but to communicate sen-

sations; not to depict life, but to interpret life.

New ideas, or, rather, age-old ideas revived and

vivified, followed fast one upon another. It was

soon found that rhythm had been neglected, that

form had largely lost its original significance, and

that, above all else, the visible world had ceased

to be employed as a vehicle for arousing emotion,

but was doing service as the actual object of

emotion.

Quite as logical as had been its predecessors, the

next step was taken by Pablo Picasso, whose basic

ideas may be found in Pythagoras, and the prin-

ciples of whose method were long

since formulated by Plato. Sublime

elementalism herewith gives place to

divine geometrizing, with the result

that we are at last freed from all

taint of nature imitation and watch

unfold before us a world of visual

imagery existing of and for itself

alone. The austere, Iberian tem-

perament of Picasso, which makes

appeal almost exclusively through an

inherent plasticity of design, is sup-

plemented in the work of Picabia by

a warmer, more sensuous tonality

and a kindred desire to create, not to

copy. Call it optical music, emo-

tional mathematics, or by whatever

term you choose, the production of

Picasso, Picabia, Bracque, Duchamp

and their colleagues cannot be dis-

missed as mere ingenious or imperti-

nent pleasantry. Something of that

rare and passionate self-absorption

which has characterized the great

seers of the past finds its reflection

in certain of these men. They lead

us, seriously and reconditely, into a

realm where subjectivity reigns su-

preme, and no one can hold that

they have not done something to¬

ward establishing a purely abstract language of

form and color.

It is futile to expend one’s energies debating

whether such manifestations have or have not any

specific place in art. The fact remains that they

DECORATION FOR THEATRE BY EMILE A.

FRANQAIS BOURDELLE

XXXII