Contemporary Art and the Carnegie Institute

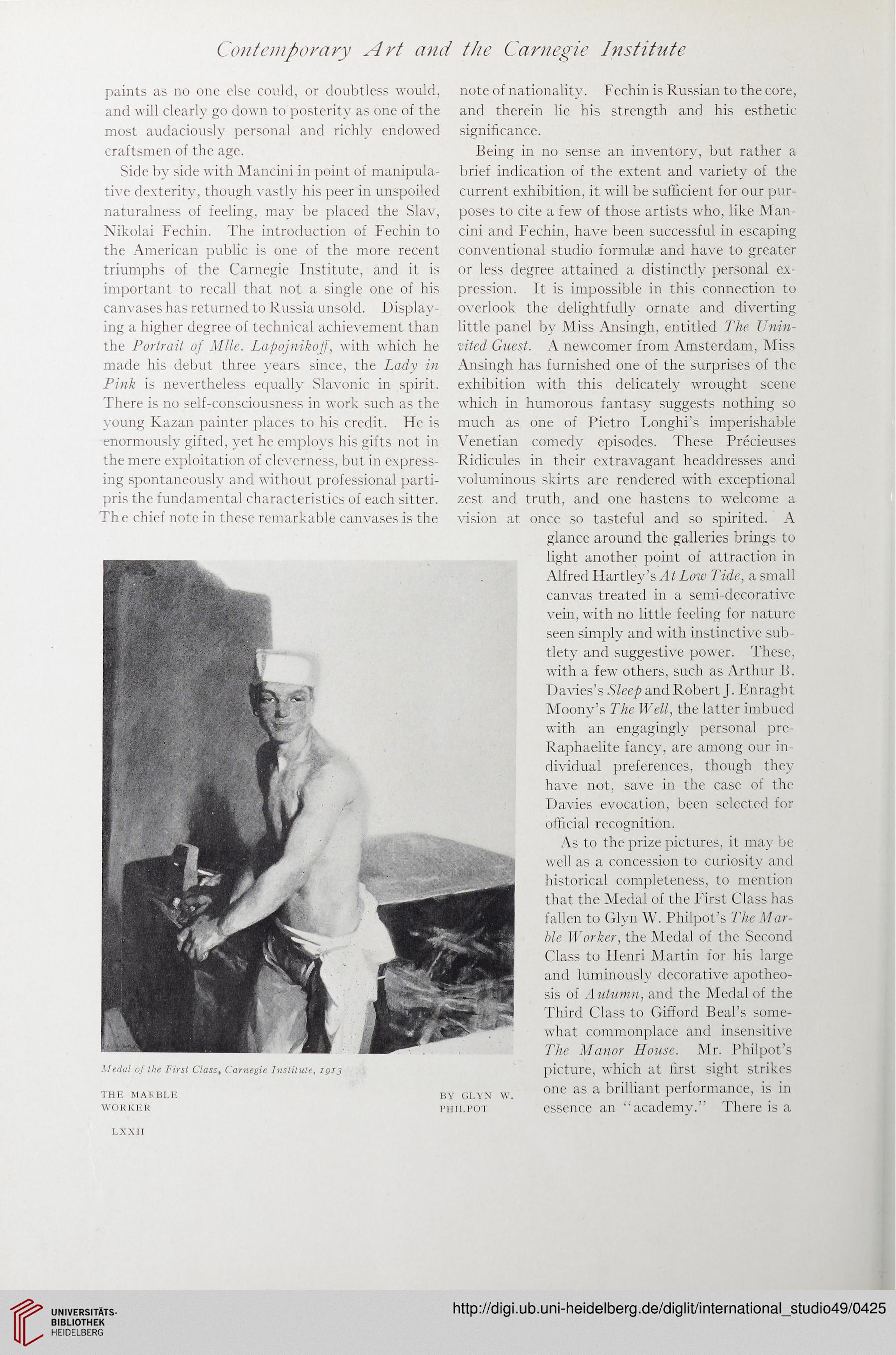

Medal of the First Class, Carnegie Institute, 1913

humorous fantasy suggests nothing so

one of Pietro Longhi’s imperishable

comedy episodes. These Precieuses

in their extravagant headdresses and

THE MARBLE

WORKER

BY GLYN W.

PHILPOT

note of nationality. Fechin is Russian to the core,

and therein lie his strength and his esthetic

significance.

Being in no sense an inventory, but rather a

brief indication of the extent and variety of the

current exhibition, it will be sufficient for our pur-

poses to cite a few of those artists who, like Man-

cini and Fechin, have been successful in escaping

conventional studio formulas and have to greater

or less degree attained a distinctly personal ex-

pression. It is impossible in this connection to

overlook the delightfully ornate and diverting

little panel by Miss Ansingh, entitled The Unin-

vited Guest. A newcomer from Amsterdam, Miss

Ansingh has furnished one of the surprises of the

exhibition with this delicately wrought scene

which in

much as

Venetian

Ridicules

voluminous skirts are rendered with exceptional

zest and

vision at

paints as no one else could, or doubtless would,

and will clearly go down to posterity as one of the

most audaciously personal and richly endowed

craftsmen of the age.

Side by side with Mancini in point of manipula-

tive dexterity, though vastly his peer in unspoiled

naturalness of feeling, may be placed the Slav,

Nikolai Fechin. The introduction of Fechin to

the American public is one of the more recent

triumphs of the Carnegie Institute, and it is

important to recall that not a single one of his

canvases has returned to Russia unsold. Display-

ing a higher degree of technical achievement than

the Portrait of Mlle. Lapojnikojf, with which he

made his debut three years since, the Lady in

Pink is nevertheless equally Slavonic in spirit.

There is no self-consciousness in work such as the

young Kazan painter places to his credit. He is

enormously gifted, yet he employs his gifts not in

the mere exploitation of cleverness, but in express-

ing spontaneously and without professional parti-

pris the fundamental characteristics of each sitter.

The chief note in these remarkable canvases is the

truth, and one hastens to welcome a

once so tasteful and so spirited. A

glance around the galleries brings to

light another point of attraction in

Alfred Hartley’s At Low Tide, a small

canvas treated in a semi-decorative

vein, with no little feeling for nature

seen simply and with instinctive sub-

tlety and suggestive power. These,

with a few others, such as Arthur B.

Davies’s Sleep and Robert J. Enraght

Moonv’s The Well, the latter imbued

with an engagingly personal pre-

Raphaelite fancy, are among our in-

dividual preferences, though they

have not, save in the case of the

Davies evocation, been selected for

official recognition.

As to the prize pictures, it may be

well as a concession to curiosity and

historical completeness, to mention

that the Medal of the First Class has

fallen to Glyn W. Philpot’s The Mar-

ble Worker, the Medal of the Second

Class to Henri Martin for his large

and luminously decorative apotheo-

sis of Autumn, and the Medal of the

Third Class to Gifford Beal’s some-

what commonplace and insensitive

The Manor House. Mr. Philpot’s

picture, which at first sight strikes

one as a brilliant performance, is in

essence an “academy.” There is a

LXXII

Medal of the First Class, Carnegie Institute, 1913

humorous fantasy suggests nothing so

one of Pietro Longhi’s imperishable

comedy episodes. These Precieuses

in their extravagant headdresses and

THE MARBLE

WORKER

BY GLYN W.

PHILPOT

note of nationality. Fechin is Russian to the core,

and therein lie his strength and his esthetic

significance.

Being in no sense an inventory, but rather a

brief indication of the extent and variety of the

current exhibition, it will be sufficient for our pur-

poses to cite a few of those artists who, like Man-

cini and Fechin, have been successful in escaping

conventional studio formulas and have to greater

or less degree attained a distinctly personal ex-

pression. It is impossible in this connection to

overlook the delightfully ornate and diverting

little panel by Miss Ansingh, entitled The Unin-

vited Guest. A newcomer from Amsterdam, Miss

Ansingh has furnished one of the surprises of the

exhibition with this delicately wrought scene

which in

much as

Venetian

Ridicules

voluminous skirts are rendered with exceptional

zest and

vision at

paints as no one else could, or doubtless would,

and will clearly go down to posterity as one of the

most audaciously personal and richly endowed

craftsmen of the age.

Side by side with Mancini in point of manipula-

tive dexterity, though vastly his peer in unspoiled

naturalness of feeling, may be placed the Slav,

Nikolai Fechin. The introduction of Fechin to

the American public is one of the more recent

triumphs of the Carnegie Institute, and it is

important to recall that not a single one of his

canvases has returned to Russia unsold. Display-

ing a higher degree of technical achievement than

the Portrait of Mlle. Lapojnikojf, with which he

made his debut three years since, the Lady in

Pink is nevertheless equally Slavonic in spirit.

There is no self-consciousness in work such as the

young Kazan painter places to his credit. He is

enormously gifted, yet he employs his gifts not in

the mere exploitation of cleverness, but in express-

ing spontaneously and without professional parti-

pris the fundamental characteristics of each sitter.

The chief note in these remarkable canvases is the

truth, and one hastens to welcome a

once so tasteful and so spirited. A

glance around the galleries brings to

light another point of attraction in

Alfred Hartley’s At Low Tide, a small

canvas treated in a semi-decorative

vein, with no little feeling for nature

seen simply and with instinctive sub-

tlety and suggestive power. These,

with a few others, such as Arthur B.

Davies’s Sleep and Robert J. Enraght

Moonv’s The Well, the latter imbued

with an engagingly personal pre-

Raphaelite fancy, are among our in-

dividual preferences, though they

have not, save in the case of the

Davies evocation, been selected for

official recognition.

As to the prize pictures, it may be

well as a concession to curiosity and

historical completeness, to mention

that the Medal of the First Class has

fallen to Glyn W. Philpot’s The Mar-

ble Worker, the Medal of the Second

Class to Henri Martin for his large

and luminously decorative apotheo-

sis of Autumn, and the Medal of the

Third Class to Gifford Beal’s some-

what commonplace and insensitive

The Manor House. Mr. Philpot’s

picture, which at first sight strikes

one as a brilliant performance, is in

essence an “academy.” There is a

LXXII