Contemporary Art and the Carnegie Institute

tional taste and approval is an issue fraught

with peculiar delicacy.

In as far as native production is concerned,

judgment may well be suspended, for modernism

is so recent an acquisition with us, and our apos-

tles of advanced ideas and practice are so mani-

festly derivative, not to say imitative, that it is

perhaps wiser to await further developments.

When it comes however to contemporary Euro-

pean art, the situation is different, for here the

Institute has already won substantial laurels, and

with courage and insight will doubtless add to

their number. It must never be forgotten that

Pittsburgh enjoys the distinction of having intro-

duced Segantini to America, that it was the first

organization to extend welcome to Cottet, Blanche,

Menard, Simon, and other members of the Societe

Nouvelle, that the Englishmen Shannon and

Nicholson, the Irishmen Lavery and Orpen, the

Glasgow School, and the modern Germans, Scandi-

navians, and Russians each found their first regular

transatlantic representation upon these same

walls. In addition to this the current one-man

displays have established a standard difficult to

parallel, beside which the Permanent Collection is

constantly acquiring choice canvases culled from

the annual shows, among which may be instanced

Whistler’s Sarasate, Menard’s Judgment of Paris,

and Simon’s Evening in the Studio.

There have of course been omissions and lapses

now and again in the generally well-sustained ex-

cellence of this programme. As a pathfinder pure

and simple Segantini, who may be classed as the

founder of the Italian Divisionist school, looms in

majestic isolation, for his fellow-workers along

kindred lines, Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh—-

that veritable trinity of the modern movement—

do not figure on the books of the Institute. There

are certain Belgians, Austrians, Poles, and

Czechs who might with advantage have been

added to the list, and one would also like to en-

counter more often the masterly characterizations

of Zuloaga, the sumptuous chromatic improvisa-

tions of Anglada, and the joyous pantheism of

Leo Putz and the Munich Scholle. Still, viewed

in perspective there are few organizations which

can boast a better record than that established by

our friends in Pittsburgh. A particular advan-

tage which the Carnegie Institute possesses is that

of judicious concentration. It is possible to do

justice to these exhibitions without undue fatigue

of body or confusion of mind. They fall within

the limits of ordinary mortal endurance, and for

this all thanks are due.

Without succumbing to sensationalism it may

in conclusion be added that these are critical times

in the development of native taste. A spirit of

unrest is unmistakably in the air. The enormous

consideration accorded the work of certain radi-

cals both past and present, the currency given the

Nietzschean dic-

tum that in order

to build up it is

first necessary to

destroy, and the

resultant ques-

tioning of acad-

emic precedent

and authority all

make it difficult

to determine upon

just what lines ex-

hibitions should

be planned. It is

clearly not enough

that the mere ma-

chinery of an in-

stitution possess-

ing the power and

prestige of the

Carnegie should

run smoothly—-

automatically, al-

most. It must

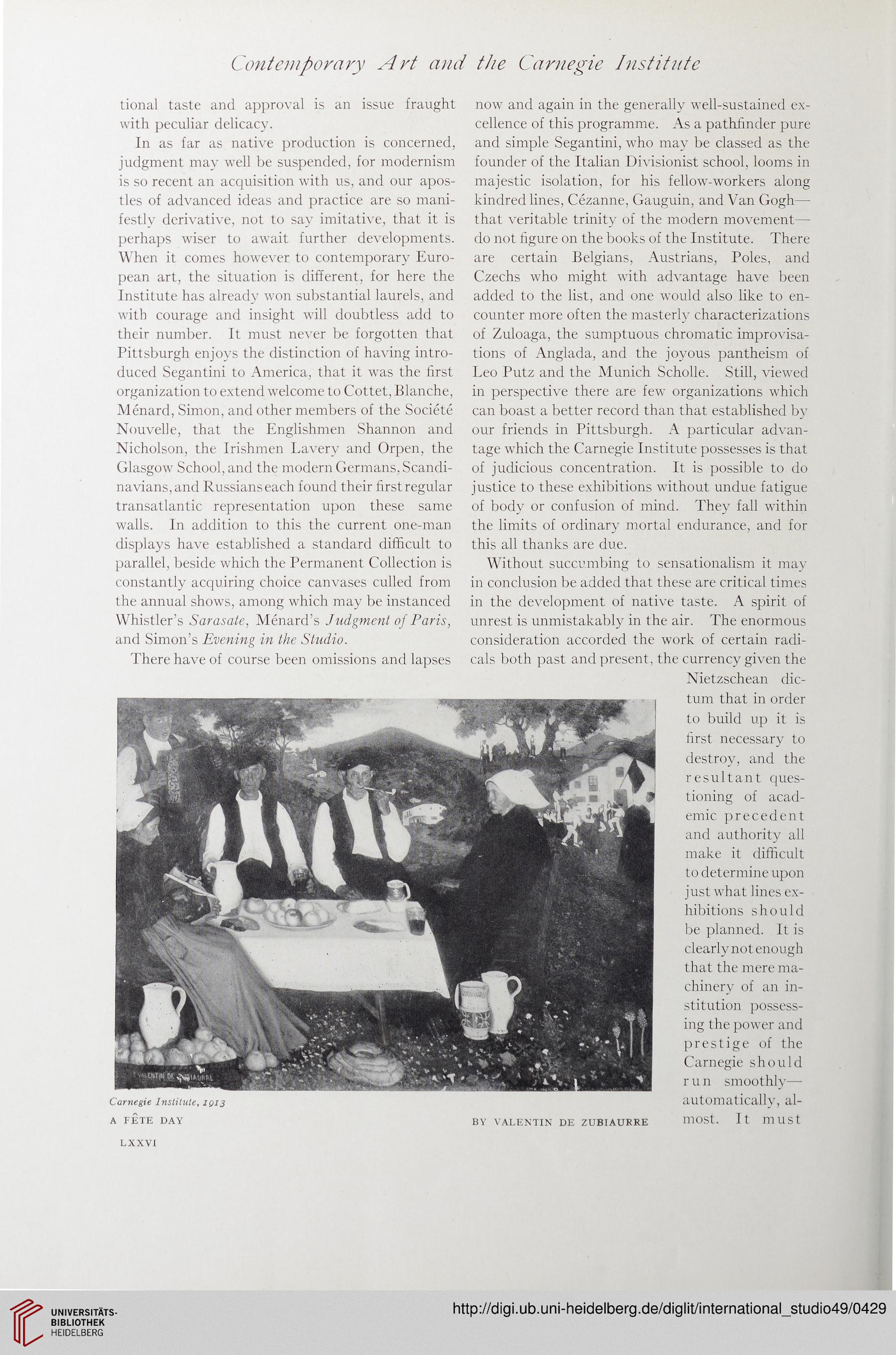

Carnegie Institute, 1913

A FETE DAY BY VALENTIN DE ZUBIAURRE

LXXV1

tional taste and approval is an issue fraught

with peculiar delicacy.

In as far as native production is concerned,

judgment may well be suspended, for modernism

is so recent an acquisition with us, and our apos-

tles of advanced ideas and practice are so mani-

festly derivative, not to say imitative, that it is

perhaps wiser to await further developments.

When it comes however to contemporary Euro-

pean art, the situation is different, for here the

Institute has already won substantial laurels, and

with courage and insight will doubtless add to

their number. It must never be forgotten that

Pittsburgh enjoys the distinction of having intro-

duced Segantini to America, that it was the first

organization to extend welcome to Cottet, Blanche,

Menard, Simon, and other members of the Societe

Nouvelle, that the Englishmen Shannon and

Nicholson, the Irishmen Lavery and Orpen, the

Glasgow School, and the modern Germans, Scandi-

navians, and Russians each found their first regular

transatlantic representation upon these same

walls. In addition to this the current one-man

displays have established a standard difficult to

parallel, beside which the Permanent Collection is

constantly acquiring choice canvases culled from

the annual shows, among which may be instanced

Whistler’s Sarasate, Menard’s Judgment of Paris,

and Simon’s Evening in the Studio.

There have of course been omissions and lapses

now and again in the generally well-sustained ex-

cellence of this programme. As a pathfinder pure

and simple Segantini, who may be classed as the

founder of the Italian Divisionist school, looms in

majestic isolation, for his fellow-workers along

kindred lines, Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh—-

that veritable trinity of the modern movement—

do not figure on the books of the Institute. There

are certain Belgians, Austrians, Poles, and

Czechs who might with advantage have been

added to the list, and one would also like to en-

counter more often the masterly characterizations

of Zuloaga, the sumptuous chromatic improvisa-

tions of Anglada, and the joyous pantheism of

Leo Putz and the Munich Scholle. Still, viewed

in perspective there are few organizations which

can boast a better record than that established by

our friends in Pittsburgh. A particular advan-

tage which the Carnegie Institute possesses is that

of judicious concentration. It is possible to do

justice to these exhibitions without undue fatigue

of body or confusion of mind. They fall within

the limits of ordinary mortal endurance, and for

this all thanks are due.

Without succumbing to sensationalism it may

in conclusion be added that these are critical times

in the development of native taste. A spirit of

unrest is unmistakably in the air. The enormous

consideration accorded the work of certain radi-

cals both past and present, the currency given the

Nietzschean dic-

tum that in order

to build up it is

first necessary to

destroy, and the

resultant ques-

tioning of acad-

emic precedent

and authority all

make it difficult

to determine upon

just what lines ex-

hibitions should

be planned. It is

clearly not enough

that the mere ma-

chinery of an in-

stitution possess-

ing the power and

prestige of the

Carnegie should

run smoothly—-

automatically, al-

most. It must

Carnegie Institute, 1913

A FETE DAY BY VALENTIN DE ZUBIAURRE

LXXV1