The Edmund Davis Collection

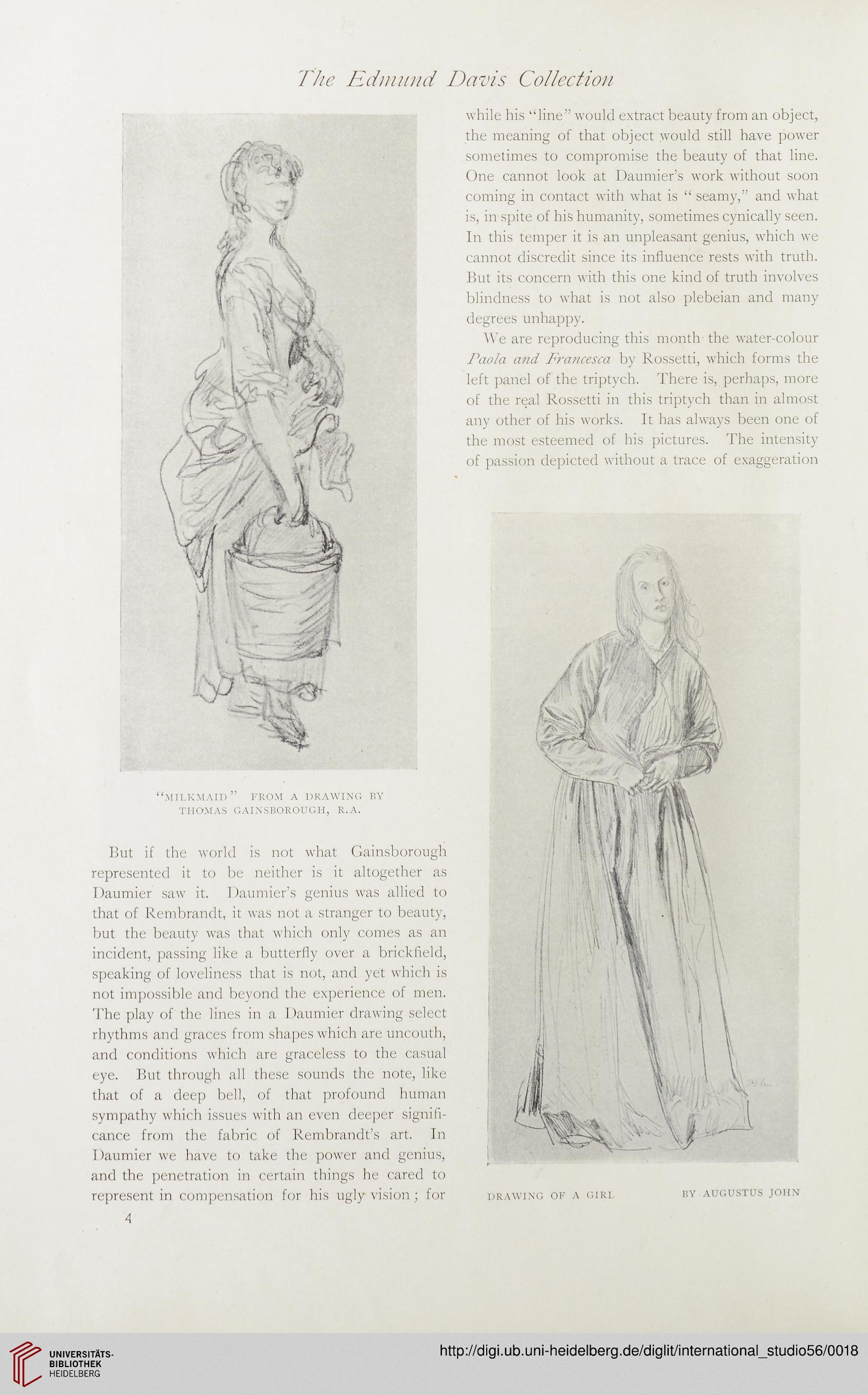

“MILKMAID ” FROM A DRAWING BY

THOMAS GAINSBOROUGH, R.A.

But if the world is not what Gainsborough

represented it to be neither is it altogether as

Daumier saw it. Daumier’s genius was allied to

that of Rembrandt, it was not a stranger to beauty,

but the beauty was that which only comes as an

incident, passing like a butterfly over a brickfield,

speaking of loveliness that is not, and yet which is

not impossible and beyond the experience of men.

The play of the lines in a Daumier drawing select

rhythms and graces from shapes which are uncouth,

and conditions which are graceless to the casual

eye. But through all these sounds the note, like

that of a deep bell, of that profound human

sympathy which issues with an even deeper signifi-

cance from the fabric of Rembrandt’s art. In

Daumier we have to take the power and genius,

and the penetration in certain things he cared to

represent in compensation for his ugly vision; for

4

while his “line” would extract beauty from an object,

the meaning of that object would still have power

sometimes to compromise the beauty of that line.

One cannot look at Daumier’s work without soon

coming in contact with what is “ seamy,” and what

is, in spite of his humanity, sometimes cynically seen.

In this temper it is an unpleasant genius, which we

cannot discredit since its influence rests with truth.

But its concern with this one kind of truth involves

blindness to what is not also plebeian and many

degrees unhappy.

We are reproducing this month the water-colour

Paola and Francesca by Rossetti, which forms the

left panel of the triptych. There is, perhaps, more

of the real Rossetti in this triptych than in almost

any other of his works. It has always been one of

the most esteemed of his pictures. The intensity

of passion depicted without a trace of exaggeration

DRAWING OF A GIRL

BY AUGUSTUS JOHN

“MILKMAID ” FROM A DRAWING BY

THOMAS GAINSBOROUGH, R.A.

But if the world is not what Gainsborough

represented it to be neither is it altogether as

Daumier saw it. Daumier’s genius was allied to

that of Rembrandt, it was not a stranger to beauty,

but the beauty was that which only comes as an

incident, passing like a butterfly over a brickfield,

speaking of loveliness that is not, and yet which is

not impossible and beyond the experience of men.

The play of the lines in a Daumier drawing select

rhythms and graces from shapes which are uncouth,

and conditions which are graceless to the casual

eye. But through all these sounds the note, like

that of a deep bell, of that profound human

sympathy which issues with an even deeper signifi-

cance from the fabric of Rembrandt’s art. In

Daumier we have to take the power and genius,

and the penetration in certain things he cared to

represent in compensation for his ugly vision; for

4

while his “line” would extract beauty from an object,

the meaning of that object would still have power

sometimes to compromise the beauty of that line.

One cannot look at Daumier’s work without soon

coming in contact with what is “ seamy,” and what

is, in spite of his humanity, sometimes cynically seen.

In this temper it is an unpleasant genius, which we

cannot discredit since its influence rests with truth.

But its concern with this one kind of truth involves

blindness to what is not also plebeian and many

degrees unhappy.

We are reproducing this month the water-colour

Paola and Francesca by Rossetti, which forms the

left panel of the triptych. There is, perhaps, more

of the real Rossetti in this triptych than in almost

any other of his works. It has always been one of

the most esteemed of his pictures. The intensity

of passion depicted without a trace of exaggeration

DRAWING OF A GIRL

BY AUGUSTUS JOHN