Permanent Collections for Small Museums

important of all, however, is a temperament sus-

ceptible to quality—the ability to feel instinctively

the truly great in contrast to the merely popular.

The possession of this intuitiveness is the only way

to know the art which is vital from that which

lacks significance or is made to flatter the vanity

of the unenlightened self-made man, art which

is merely the product of commercial prosperity;

for the academies and other institutions have

often been more liberal in their recognition of the

mediocre, than of the great, artist. Moreover, the

museum director must have the courage to defy

public opinion by selecting the best, since the

best is not usually popular.

The fact that an artist has received many deco-

rations and honours is not, by any means, conclu-

sive evidence that he is a master. The names of

half-a-dozen European painters could be men-

tioned who are discredited to-day even though they

possess more honours than all the really immortal

artists put together. As a matter of fact, the

honours usually go to the energetic business man

rather than to the true artist. The artist, be-

ing too busy creating, is oblivious to the public’s

taste, good or bad, whereas the business man is

producing only work which he knows the public

will buy, the proceeds of which help in many ways

to bring about official recognition. This condition

discourages and retards the production of the best

in all of the arts—particularly painting, sculpture,

literature and the drama, for true art has never yet

been created by exponents of either one of these

branches who contemplated and moulded their

work according to the fancies of their patrons.

The artist must express himself and his time and,

if he has confidence that he has something to say,

this he will do, and the value of his work will de-

pend upon the breadth and originality of his

outlook. There has always been a diversity of

opinion as to how much historical significance

should enter into the selection of works of art

for the permanent collection of a public museum.

With art museums of a national character, as,

for instance, the Metropolitan or the Boston,

Washington or Chicago Museums, there can be

little question that historical as well as aesthetic

comprehensiveness is imperative. In the smaller

museums this comprehensiveness has never been

carried out or seriously attempted. I believe,

however, that the smallness of a museum might be

an advantage in forming a collection of both his-

torical and aesthetic importance.

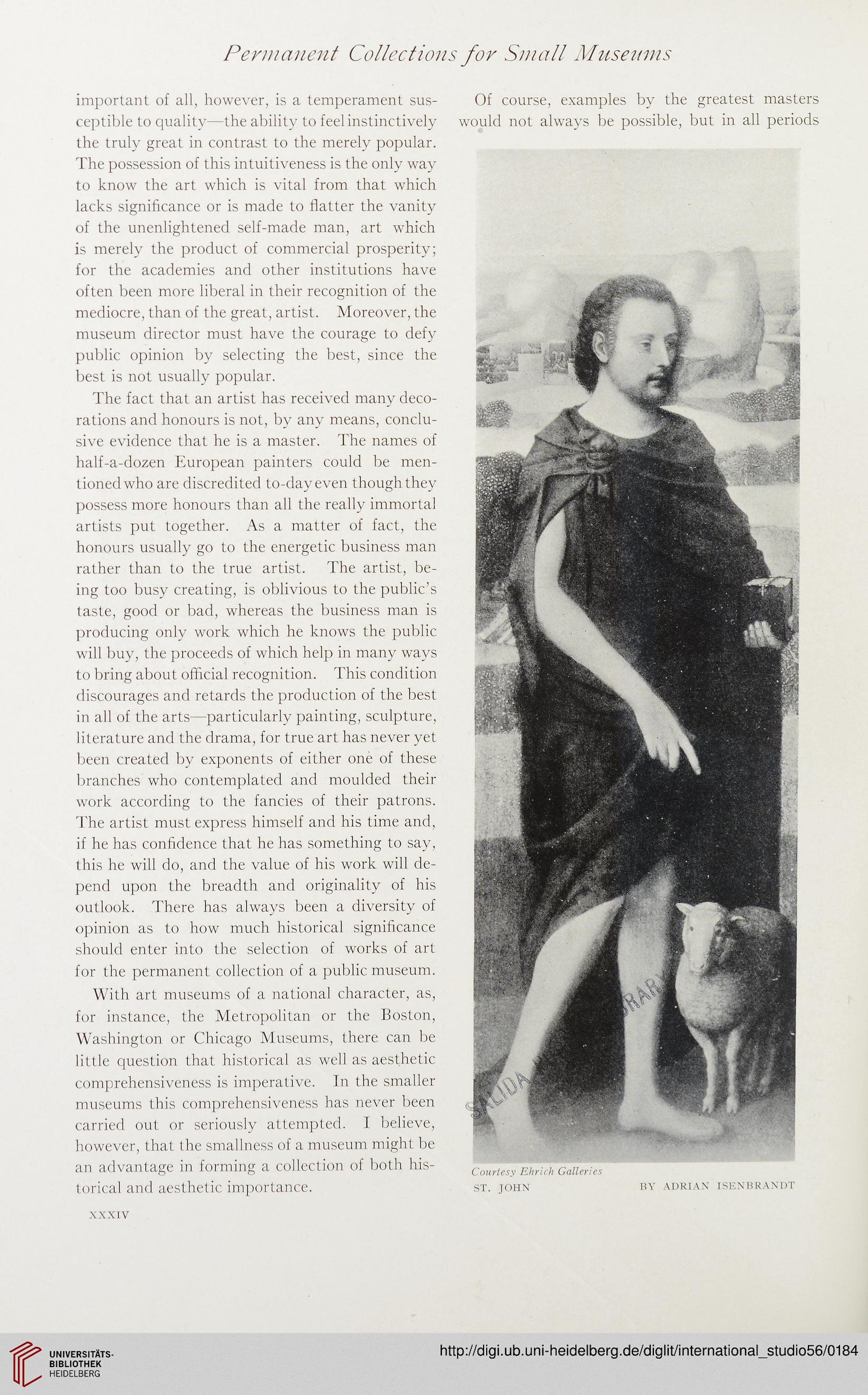

Of course, examples by the greatest masters

would not always be possible, but in all periods

Courtesy Ehrich Galleries

ST. JOHN BY ADRIAN ISENBRANDT

XXXIV

important of all, however, is a temperament sus-

ceptible to quality—the ability to feel instinctively

the truly great in contrast to the merely popular.

The possession of this intuitiveness is the only way

to know the art which is vital from that which

lacks significance or is made to flatter the vanity

of the unenlightened self-made man, art which

is merely the product of commercial prosperity;

for the academies and other institutions have

often been more liberal in their recognition of the

mediocre, than of the great, artist. Moreover, the

museum director must have the courage to defy

public opinion by selecting the best, since the

best is not usually popular.

The fact that an artist has received many deco-

rations and honours is not, by any means, conclu-

sive evidence that he is a master. The names of

half-a-dozen European painters could be men-

tioned who are discredited to-day even though they

possess more honours than all the really immortal

artists put together. As a matter of fact, the

honours usually go to the energetic business man

rather than to the true artist. The artist, be-

ing too busy creating, is oblivious to the public’s

taste, good or bad, whereas the business man is

producing only work which he knows the public

will buy, the proceeds of which help in many ways

to bring about official recognition. This condition

discourages and retards the production of the best

in all of the arts—particularly painting, sculpture,

literature and the drama, for true art has never yet

been created by exponents of either one of these

branches who contemplated and moulded their

work according to the fancies of their patrons.

The artist must express himself and his time and,

if he has confidence that he has something to say,

this he will do, and the value of his work will de-

pend upon the breadth and originality of his

outlook. There has always been a diversity of

opinion as to how much historical significance

should enter into the selection of works of art

for the permanent collection of a public museum.

With art museums of a national character, as,

for instance, the Metropolitan or the Boston,

Washington or Chicago Museums, there can be

little question that historical as well as aesthetic

comprehensiveness is imperative. In the smaller

museums this comprehensiveness has never been

carried out or seriously attempted. I believe,

however, that the smallness of a museum might be

an advantage in forming a collection of both his-

torical and aesthetic importance.

Of course, examples by the greatest masters

would not always be possible, but in all periods

Courtesy Ehrich Galleries

ST. JOHN BY ADRIAN ISENBRANDT

XXXIV