Edward Berge, Sculptor

ticular gratitude of the instruction given him by

Verlet at Julian’s, and of the knowledge he

gained at Rodin’s school, where he came into

contact with the great master himself.

His first salon pictures—the year was 1901—

were the exquisite Muse Finding the Head of

Orpheus and The Scalp, casts that brought him

immediate recognition.

The Scalp, which is now in bronze, is a powerful

bit of realism. The subject is an Indian who,

transported with gruesome joy, stands in triumph

over the body of his enemy that rolls beneath his

feet.

The figure is built up in a powerful manner,

the modelling so broad, so bold, bespeaking that

almost fierce exultation that fires an artist, when,

at the moment of inspiration, the full realization

of his subject blazes upon him and he springs

forward to put his thought into instant execution.

At such moments one’s powers of expression

find outlet with marvellous facility and it is just

this ease that, in Mr. Berge’s Indian piece, makes

the upward swing of the lithe, muscular body,

held, as it is, in a superbly balanced pose, so

effective, so potent as a description of passionate

action. Histrionically, this is one of the sculptor’s

strongest performances.

An example of commissioned work that il-

lustrates the full maturity of his powers in

portraiture is the statue of Col. George Armistead,

erected at Fort McHenry last fall. It is a noble,

dignified monument and one that has uncommon

vitality and impressiveness as a study of char-

acter. The figure is heroic in size and is of bronze.

It surmounts a granite pedestal on a hill com-

manding a wide sweep of the Patapsco River,

presenting from any angle a sharp, clean-cut

silhouette of great elegance and grace.

Mr. Berge’s work is essentially and uncom-

promisingly direct and unaffected, based, one

would say, upon views of life that are above

everything else healthful and sane. Not once in

the whole range of his production has he dis-

played the slightest tendency toward eccentricity

or sensationalism. In fact, the impulse in the

other direction seems to influence him so strongly

that his effort to avoid even the suggestion of

such things, or of being lured into the pitfalls of

sentimentalism or insincerity, appear almost

aggressive.

He evidently has no use for “coloratura”

sculpture, and scorning bravura, his processes

LX

of elimination are so sharply defined, where

ornamentation is concerned, that his work un-

doubtedly is less general in its appeal to the

unthinking public than if he made more conces-

sions to decoration.

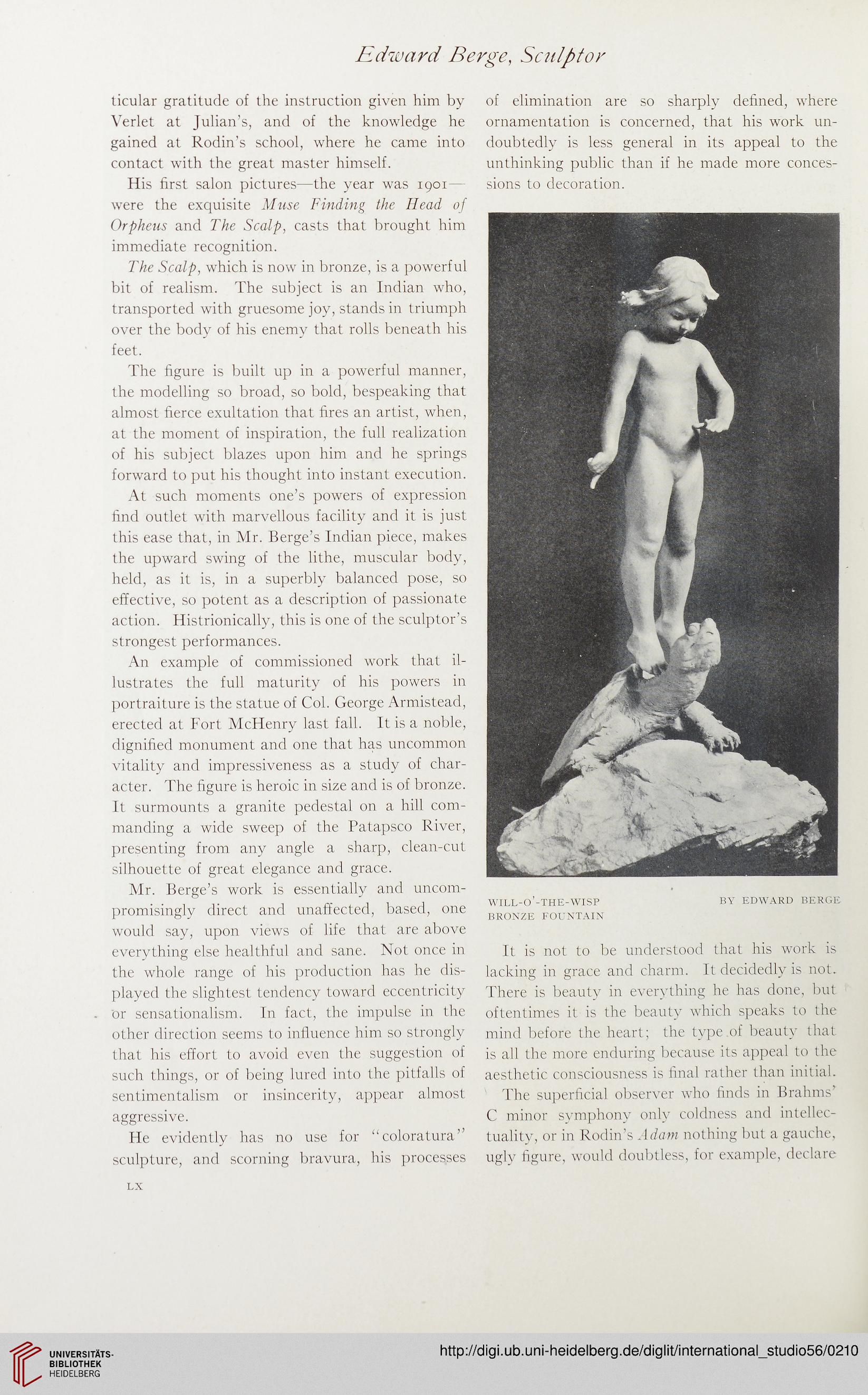

WILL-O’-THE-WISP BY EDWARD BERGE

BRONZE FOUNTAIN

It is not to be understood that his work is

lacking in grace and charm. It decidedly is not.

There is beauty in everything he has done, but

oftentimes it is the beauty which speaks to the

mind before the heart; the type of beauty that

is all the more enduring because its appeal to the

aesthetic consciousness is final rather than initial.

The superficial observer who finds in Brahms’

C minor symphony only coldness and intellec-

tuality, or in Rodin’s Adam nothing but a gauche,

ugly figure, would doubtless, for example, declare

ticular gratitude of the instruction given him by

Verlet at Julian’s, and of the knowledge he

gained at Rodin’s school, where he came into

contact with the great master himself.

His first salon pictures—the year was 1901—

were the exquisite Muse Finding the Head of

Orpheus and The Scalp, casts that brought him

immediate recognition.

The Scalp, which is now in bronze, is a powerful

bit of realism. The subject is an Indian who,

transported with gruesome joy, stands in triumph

over the body of his enemy that rolls beneath his

feet.

The figure is built up in a powerful manner,

the modelling so broad, so bold, bespeaking that

almost fierce exultation that fires an artist, when,

at the moment of inspiration, the full realization

of his subject blazes upon him and he springs

forward to put his thought into instant execution.

At such moments one’s powers of expression

find outlet with marvellous facility and it is just

this ease that, in Mr. Berge’s Indian piece, makes

the upward swing of the lithe, muscular body,

held, as it is, in a superbly balanced pose, so

effective, so potent as a description of passionate

action. Histrionically, this is one of the sculptor’s

strongest performances.

An example of commissioned work that il-

lustrates the full maturity of his powers in

portraiture is the statue of Col. George Armistead,

erected at Fort McHenry last fall. It is a noble,

dignified monument and one that has uncommon

vitality and impressiveness as a study of char-

acter. The figure is heroic in size and is of bronze.

It surmounts a granite pedestal on a hill com-

manding a wide sweep of the Patapsco River,

presenting from any angle a sharp, clean-cut

silhouette of great elegance and grace.

Mr. Berge’s work is essentially and uncom-

promisingly direct and unaffected, based, one

would say, upon views of life that are above

everything else healthful and sane. Not once in

the whole range of his production has he dis-

played the slightest tendency toward eccentricity

or sensationalism. In fact, the impulse in the

other direction seems to influence him so strongly

that his effort to avoid even the suggestion of

such things, or of being lured into the pitfalls of

sentimentalism or insincerity, appear almost

aggressive.

He evidently has no use for “coloratura”

sculpture, and scorning bravura, his processes

LX

of elimination are so sharply defined, where

ornamentation is concerned, that his work un-

doubtedly is less general in its appeal to the

unthinking public than if he made more conces-

sions to decoration.

WILL-O’-THE-WISP BY EDWARD BERGE

BRONZE FOUNTAIN

It is not to be understood that his work is

lacking in grace and charm. It decidedly is not.

There is beauty in everything he has done, but

oftentimes it is the beauty which speaks to the

mind before the heart; the type of beauty that

is all the more enduring because its appeal to the

aesthetic consciousness is final rather than initial.

The superficial observer who finds in Brahms’

C minor symphony only coldness and intellec-

tuality, or in Rodin’s Adam nothing but a gauche,

ugly figure, would doubtless, for example, declare