Thought and Thinking in Architecture

which to determine what you think about the

architecture of St. Thomas’ Church, on Fifth

Avenue, is to store your mind with what Ruskin

thought about Giotto’s Tower in Florence.

Given some knowledge of style, and of historic

precedents and the like, and a certain amount of

discrimination, good taste and perception—what

of the more intangible qualities that form very

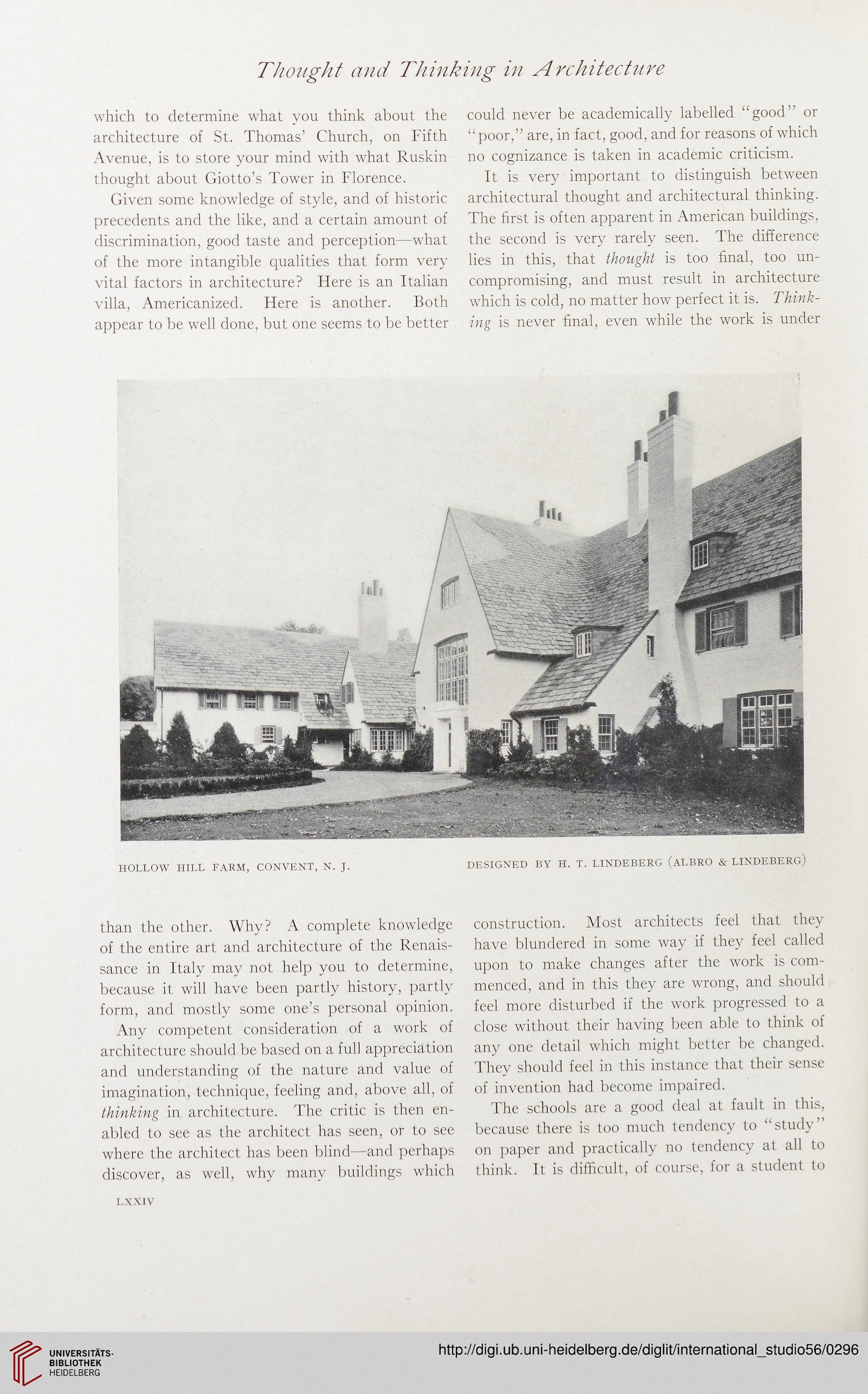

vital factors in architecture? Here is an Italian

villa, Americanized. Here is another. Both

appear to be well done, but one seems to be better

could never be academically labelled “good” or

“poor,” are, in fact, good, and for reasons of which

no cognizance is taken in academic criticism.

It is very important to distinguish between

architectural thought and architectural thinking.

The first is often apparent in American buildings,

the second is very rarely seen. The difference

lies in this, that thought is too final, too un-

compromising, and must result in architecture

which is cold, no matter how perfect it is. Think-

ing is never final, even while the work is under

HOLLOW HILL FARM, CONVENT, N. J.

DESIGNED BY H. T. LINDEBERG (ALBRO & LINDEBERG)

than the other. Why? A complete knowledge

of the entire art and architecture of the Renais-

sance in Italy may not help you to determine,

because it will have been partly history, partly

form, and mostly some one’s personal opinion.

Any competent consideration of a work of

architecture should be based on a full appreciation

and understanding of the nature and value of

imagination, technique, feeling and, above all, of

thinking in architecture. The critic is then en-

abled to see as the architect has seen, or to see

where the architect has been blind—and perhaps

discover, as well, why many buildings which

construction. Most architects feel that they

have blundered in some way if they feel called

upon to make changes after the work is com-

menced, and in this they are wrong, and should

feel more disturbed if the work progressed to a

close without their having been able to think of

any one detail which might better be changed.

They should feel in this instance that their sense

of invention had become impaired.

The schools are a good deal at fault in this,

because there is too much tendency to “study”

on paper and practically no tendency at all to

think. It is difficult, of course, for a student to

LXXIV

which to determine what you think about the

architecture of St. Thomas’ Church, on Fifth

Avenue, is to store your mind with what Ruskin

thought about Giotto’s Tower in Florence.

Given some knowledge of style, and of historic

precedents and the like, and a certain amount of

discrimination, good taste and perception—what

of the more intangible qualities that form very

vital factors in architecture? Here is an Italian

villa, Americanized. Here is another. Both

appear to be well done, but one seems to be better

could never be academically labelled “good” or

“poor,” are, in fact, good, and for reasons of which

no cognizance is taken in academic criticism.

It is very important to distinguish between

architectural thought and architectural thinking.

The first is often apparent in American buildings,

the second is very rarely seen. The difference

lies in this, that thought is too final, too un-

compromising, and must result in architecture

which is cold, no matter how perfect it is. Think-

ing is never final, even while the work is under

HOLLOW HILL FARM, CONVENT, N. J.

DESIGNED BY H. T. LINDEBERG (ALBRO & LINDEBERG)

than the other. Why? A complete knowledge

of the entire art and architecture of the Renais-

sance in Italy may not help you to determine,

because it will have been partly history, partly

form, and mostly some one’s personal opinion.

Any competent consideration of a work of

architecture should be based on a full appreciation

and understanding of the nature and value of

imagination, technique, feeling and, above all, of

thinking in architecture. The critic is then en-

abled to see as the architect has seen, or to see

where the architect has been blind—and perhaps

discover, as well, why many buildings which

construction. Most architects feel that they

have blundered in some way if they feel called

upon to make changes after the work is com-

menced, and in this they are wrong, and should

feel more disturbed if the work progressed to a

close without their having been able to think of

any one detail which might better be changed.

They should feel in this instance that their sense

of invention had become impaired.

The schools are a good deal at fault in this,

because there is too much tendency to “study”

on paper and practically no tendency at all to

think. It is difficult, of course, for a student to

LXXIV