Thought and Thinking in Architecture

feeling. Architectural knowledge of form in this

country, thanks to the niceties of McKim, Mead

& White, is in a flourishing condition—perhaps

we know too much about form. Architectural

feeling, however, is rare, and stamps the works

of those architects who have quietly come to be

known as the really significant architects of this

country.

The virility and real worth of Bertram G.

Goodhue’s work lies not in the fact that he knows

the Gothic style (which might be reckoned

relatively unimportant), but in the fact that he

feels the Gothic style which is vastly important,

and which makes his work that of an architect,

in the fullest strength of the designation—not an

archaeologist or a mere scholar. It is so with the

Italian Renaissance in the hands of Charles A.

Platt. His feeling for the style, not the accuracy

of his knowledge of its forms, makes his work

remarkable. Both Mr. Goodhue and Mr. Platt,

however, might be called stylists, and to some

degree might be called conservatives. And

American architecture should be as thankful for

their conservatism as it is for the conservatism

of McKim, Mead & White.

It is not so difficult, therefore, to determine

wherein lies a large part of the merit of their

work. It is more difficult to determine wherein

lies the peculiar excellence of the work of Harrie

T. Lincleberg (late designer of the firm of Albro

& Lindeberg), for he is neither a stylist nor a

conservative, although his work bears a distinct

stamp of style and to the extent that it is re-

markably well-mannered, might also be called

conservative.

There is also to be discerned in it a nice know-

ledge of form, without form having jealously

been made an idol, a great deal of feeling without

too much “temperament,” manner without

mannerism, originality without anarchy and,

above all, a sort of fresh spontaneity which has

resulted from architectural thinking and archi-

tectural imagination.

I have been asked, “In what style does Mr

Lindeberg work?” Need he work in any style?

There happen to be a good many people whose

vision is limited by Style (with a capital “S”)—

architects, critics, and laymen. This is un-

fortunate, most with the architect, who is

producing; next with the critic, who is explain-

ing; least with the layman, much as it limits his

capability of vision.

Now the great architectural axiom, with regard

to style, is that it should be the means, and not

the end of the architect’s endeavour. It is the

same with form. Architectural forms are the

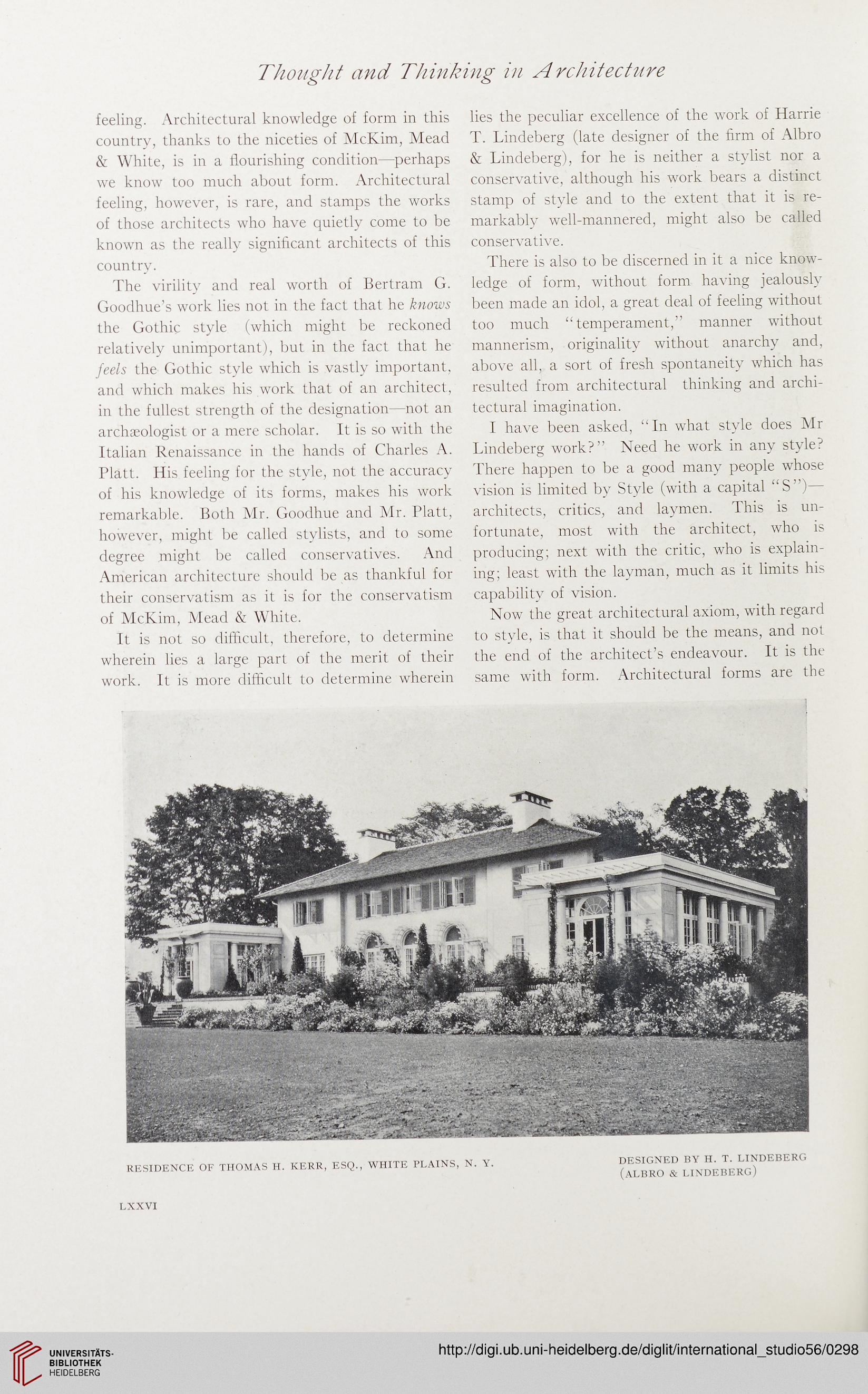

RESIDENCE OF THOMAS H. KERR, ESQ., WHITE PLAINS, N. Y.

DESIGNED BY H. T. LINDEBERG

(ALBRO & LINDEBERG)

LXXVI

feeling. Architectural knowledge of form in this

country, thanks to the niceties of McKim, Mead

& White, is in a flourishing condition—perhaps

we know too much about form. Architectural

feeling, however, is rare, and stamps the works

of those architects who have quietly come to be

known as the really significant architects of this

country.

The virility and real worth of Bertram G.

Goodhue’s work lies not in the fact that he knows

the Gothic style (which might be reckoned

relatively unimportant), but in the fact that he

feels the Gothic style which is vastly important,

and which makes his work that of an architect,

in the fullest strength of the designation—not an

archaeologist or a mere scholar. It is so with the

Italian Renaissance in the hands of Charles A.

Platt. His feeling for the style, not the accuracy

of his knowledge of its forms, makes his work

remarkable. Both Mr. Goodhue and Mr. Platt,

however, might be called stylists, and to some

degree might be called conservatives. And

American architecture should be as thankful for

their conservatism as it is for the conservatism

of McKim, Mead & White.

It is not so difficult, therefore, to determine

wherein lies a large part of the merit of their

work. It is more difficult to determine wherein

lies the peculiar excellence of the work of Harrie

T. Lincleberg (late designer of the firm of Albro

& Lindeberg), for he is neither a stylist nor a

conservative, although his work bears a distinct

stamp of style and to the extent that it is re-

markably well-mannered, might also be called

conservative.

There is also to be discerned in it a nice know-

ledge of form, without form having jealously

been made an idol, a great deal of feeling without

too much “temperament,” manner without

mannerism, originality without anarchy and,

above all, a sort of fresh spontaneity which has

resulted from architectural thinking and archi-

tectural imagination.

I have been asked, “In what style does Mr

Lindeberg work?” Need he work in any style?

There happen to be a good many people whose

vision is limited by Style (with a capital “S”)—

architects, critics, and laymen. This is un-

fortunate, most with the architect, who is

producing; next with the critic, who is explain-

ing; least with the layman, much as it limits his

capability of vision.

Now the great architectural axiom, with regard

to style, is that it should be the means, and not

the end of the architect’s endeavour. It is the

same with form. Architectural forms are the

RESIDENCE OF THOMAS H. KERR, ESQ., WHITE PLAINS, N. Y.

DESIGNED BY H. T. LINDEBERG

(ALBRO & LINDEBERG)

LXXVI