Wood-blocks

cuted for Proverbs Exemplified by John Trusler

of Bath, England, and for proverbs by the same

author, Hanard, Bath, in 1790. It was also used

on a pack of cards and is exceedingly rare.)

In 1471, when Albert Diirer appears, wood en-

graving suddenly rises to perfection without going

beyond its primitive condition of simplicity.

Traced with breadth and decision, the drawings

of Diirer teach us the concise, vigorous manner

demanded by this kind of art. He did works

of extraordinary, often colossal, size, that could

be rarely used, being suitable only for the orna-

mentation of the partitions of a vestibule, or the

walls of a gallery or

palace. Wood-engrav¬

ing seems above all

suitable for the illus¬

tration of books, and

the next great man in

the history of wood-

engraving, Hans Hol¬

bein, born in 1497,

gave admirable models

to it, models that have

not been surpassed.

On frames smaller than

the palm of the hand,

often but an inch

square, were introduced

whole pictures. Within

the microscopic dimen¬

sions of a letter, Hol¬

bein has represented

the drama of Death,

twenty-four times repeated. The narrowing of

the field seemed to only spur on the artist, such

life and expression does he display.

Geoffroi Tory imported the Italian style of the

Renaissance into our wood-engraving, in which,

up to that time, had appeared only a Gothic

archaism or the Gallic spirit, with its familiar

turn, its ironical naivete, its malice. French and

Italian artists of the first rank have not disdained

to write upon wood the inventions that put in

relief their knowledge and that of others. As

Titian painted with great pen-strokes the mas-

ter-pieces Bokdrini was to cut, as Jean de Calcar

drew at Venice the magnificent plates for the

“Anatomy” of the celebrated Vesali, so Jean

Goujou illustrated the translation of Vitruvius

by Jean Martin.

From about 1530 the art of wood-engraving in

the usual manner began to make considerable

progress in Italy, and many of the cuts executed

in that country between 1540 and 1580 may vie

with the best wood-engravings of the same period

executed in Germany. The engravers began to

execute their subjects in a more delicate and

elaborate manner—the texture of different sub-

stances is indicated more correctly; the foliage of

trees is more natural; and the fur and feathers of

animals are discriminated with considerable

ability.

Wood-engraving in Germany at the close of the

sixteenth century appears to have greatly de-

clined; the old race of

artists who furnished

designs for the wood-

engraver had become

extinct and their places

were not supplied by

others. The more ex-

pensive works were

now illustrated with

copper plates.

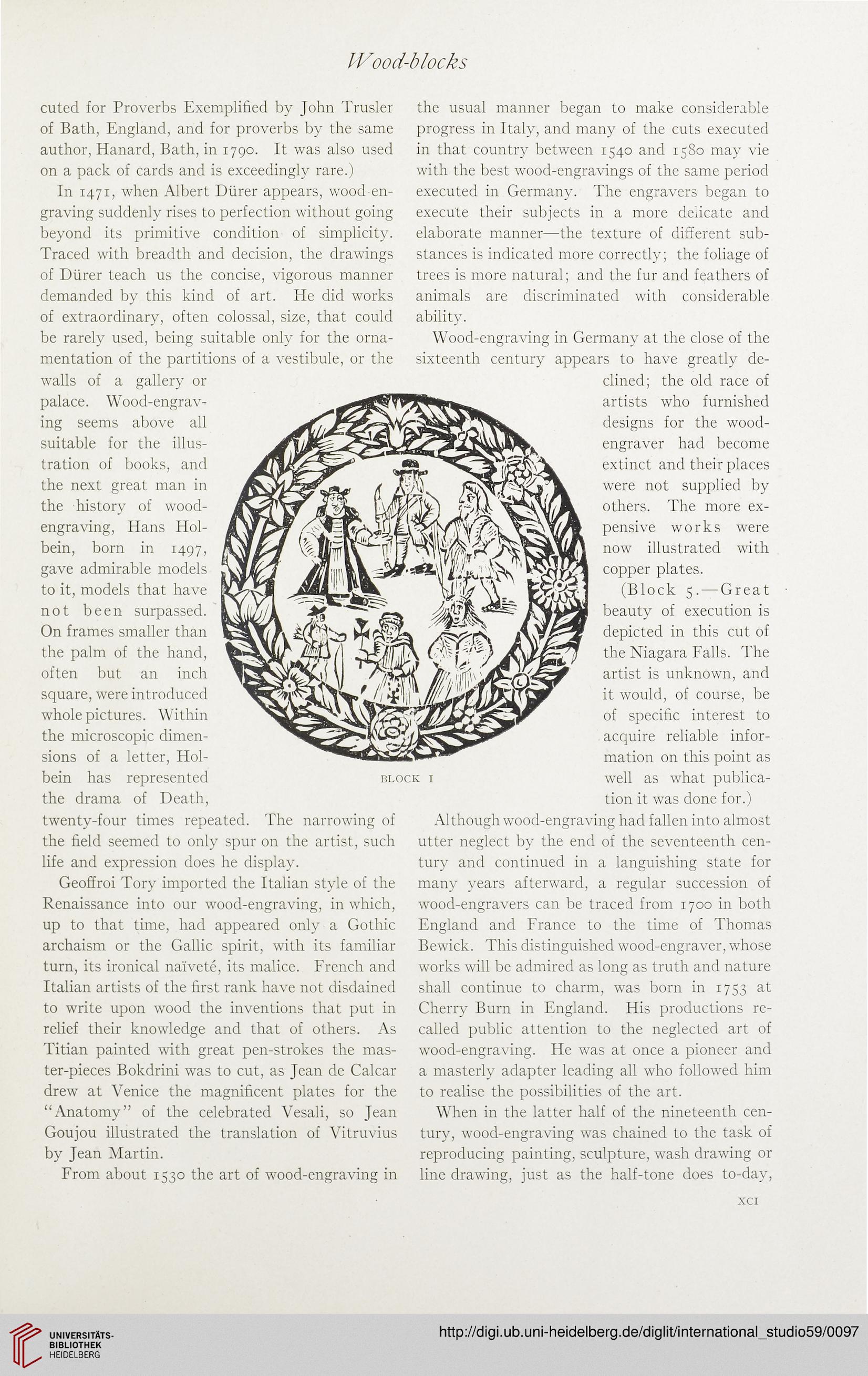

(Block 5.—Great

beauty of execution is

depicted in this cut of

the Niagara Falls. The

artist is unknown, and

it would, of course, be

of specific interest to

acquire reliable infor-

mation on this point as

well as what publica-

tion it was done for.)

Although wood-engraving had fallen into almost

utter neglect by the end of the seventeenth cen-

tury and continued in a languishing state for

many years afterward, a regular succession of

wood-engravers can be traced from 1700 in both

England and France to the time of Thomas

Bewick. This distinguished wood-engraver, whose

works will be admired as long as truth and nature

shall continue to charm, was born in 1753 at

Cherry Burn in England. His productions re-

called public attention to the neglected art of

wood-engraving. He was at once a pioneer and

a masterly adapter leading all who followed him

to realise the possibilities of the art.

When in the latter half of the nineteenth cen-

tury, wood-engraving was chained to the task of

reproducing painting, sculpture, wash drawing or

line drawing, just as the half-tone does to-day,

block 1

xci

cuted for Proverbs Exemplified by John Trusler

of Bath, England, and for proverbs by the same

author, Hanard, Bath, in 1790. It was also used

on a pack of cards and is exceedingly rare.)

In 1471, when Albert Diirer appears, wood en-

graving suddenly rises to perfection without going

beyond its primitive condition of simplicity.

Traced with breadth and decision, the drawings

of Diirer teach us the concise, vigorous manner

demanded by this kind of art. He did works

of extraordinary, often colossal, size, that could

be rarely used, being suitable only for the orna-

mentation of the partitions of a vestibule, or the

walls of a gallery or

palace. Wood-engrav¬

ing seems above all

suitable for the illus¬

tration of books, and

the next great man in

the history of wood-

engraving, Hans Hol¬

bein, born in 1497,

gave admirable models

to it, models that have

not been surpassed.

On frames smaller than

the palm of the hand,

often but an inch

square, were introduced

whole pictures. Within

the microscopic dimen¬

sions of a letter, Hol¬

bein has represented

the drama of Death,

twenty-four times repeated. The narrowing of

the field seemed to only spur on the artist, such

life and expression does he display.

Geoffroi Tory imported the Italian style of the

Renaissance into our wood-engraving, in which,

up to that time, had appeared only a Gothic

archaism or the Gallic spirit, with its familiar

turn, its ironical naivete, its malice. French and

Italian artists of the first rank have not disdained

to write upon wood the inventions that put in

relief their knowledge and that of others. As

Titian painted with great pen-strokes the mas-

ter-pieces Bokdrini was to cut, as Jean de Calcar

drew at Venice the magnificent plates for the

“Anatomy” of the celebrated Vesali, so Jean

Goujou illustrated the translation of Vitruvius

by Jean Martin.

From about 1530 the art of wood-engraving in

the usual manner began to make considerable

progress in Italy, and many of the cuts executed

in that country between 1540 and 1580 may vie

with the best wood-engravings of the same period

executed in Germany. The engravers began to

execute their subjects in a more delicate and

elaborate manner—the texture of different sub-

stances is indicated more correctly; the foliage of

trees is more natural; and the fur and feathers of

animals are discriminated with considerable

ability.

Wood-engraving in Germany at the close of the

sixteenth century appears to have greatly de-

clined; the old race of

artists who furnished

designs for the wood-

engraver had become

extinct and their places

were not supplied by

others. The more ex-

pensive works were

now illustrated with

copper plates.

(Block 5.—Great

beauty of execution is

depicted in this cut of

the Niagara Falls. The

artist is unknown, and

it would, of course, be

of specific interest to

acquire reliable infor-

mation on this point as

well as what publica-

tion it was done for.)

Although wood-engraving had fallen into almost

utter neglect by the end of the seventeenth cen-

tury and continued in a languishing state for

many years afterward, a regular succession of

wood-engravers can be traced from 1700 in both

England and France to the time of Thomas

Bewick. This distinguished wood-engraver, whose

works will be admired as long as truth and nature

shall continue to charm, was born in 1753 at

Cherry Burn in England. His productions re-

called public attention to the neglected art of

wood-engraving. He was at once a pioneer and

a masterly adapter leading all who followed him

to realise the possibilities of the art.

When in the latter half of the nineteenth cen-

tury, wood-engraving was chained to the task of

reproducing painting, sculpture, wash drawing or

line drawing, just as the half-tone does to-day,

block 1

xci