lnceRnAcionAL

of an inspired imagination are always worthy of

respect and study.

The Maya had considerable but by no means

complete mastery of the technical difficulties of

representing objects of three dimensions upon a

surface with only two. High and low relief show

something of a transition in this process. In

foreshortening, they greatly excelled the Egyp-

tians in that they were sufficiently skilled to

draw the body in pure profile, as well as repre-

senting the legs and feet in a variety of sitting

and reclining positions. The real difficulty in the

development of perspective was that the artist's

previous knowledge of the subject interfered

with his visual impressions. He knew that a

man possessed two arms and so felt constrained

to always draw two arms in full view. The Maya

artists achieved a sort of compromise between

appearance and reality. When they could not

find a way to correct a drawing, they at least

succeeded by graceful and pleasing treatment in

distracting attention from any errors in delinea-

tion.

The principal methods employed by the

Maya in the graphic and plastic arts differed

little from those of better known lands. Carving

in wood and stone and modeling in clay and

stucco were widely practiced. At the time from

which the remains of their art date they were

living, like the Mexicans, in an age of stone. The

elaborate monuments and temple decorations

were cut and carved with stone implements.

These people might have accomplished greater

wonders if they had had fine grained marble

instead of coarse, uneven limestone and iron or

bronze chisels instead of unwieldy stone knives.

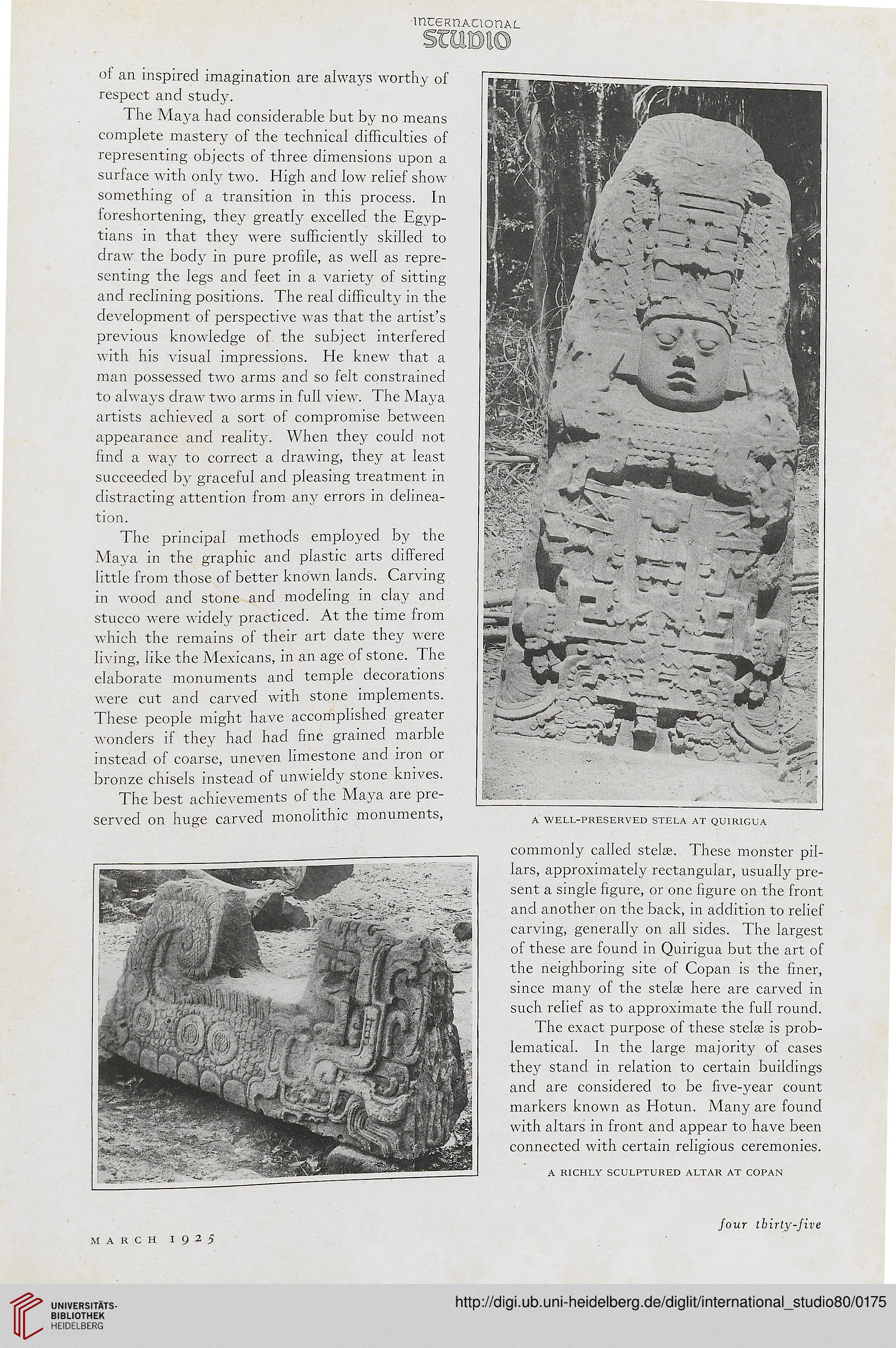

The best achievements of the Maya are pre-

served on huge carved monolithic monuments, A WELL.PRESERVED SXELA AT QUIRICUA

commonly called stelae. These monster pil-

lars, approximately rectangular, usually pre-

sent a single figure, or one figure on the front

and another on the back, in addition to relief

carving, generally on all sides. The largest

of these are found in Quirigua but the art of

the neighboring site of Copan is the finer,

since many of the stelse here are carved in

such relief as to approximate the full round.

The exact purpose of these stela? is prob-

lematical. In the large majority of cases

they stand in relation to certain buildings

and are considered to be five-year count

markers known as Hotun. Many are found

with altars in front and appear to have been

connected with certain religious ceremonies.

A RICHLY SCULPTURED ALTAR AT COPAN

MARCH I925

Jour thirty-Jive

of an inspired imagination are always worthy of

respect and study.

The Maya had considerable but by no means

complete mastery of the technical difficulties of

representing objects of three dimensions upon a

surface with only two. High and low relief show

something of a transition in this process. In

foreshortening, they greatly excelled the Egyp-

tians in that they were sufficiently skilled to

draw the body in pure profile, as well as repre-

senting the legs and feet in a variety of sitting

and reclining positions. The real difficulty in the

development of perspective was that the artist's

previous knowledge of the subject interfered

with his visual impressions. He knew that a

man possessed two arms and so felt constrained

to always draw two arms in full view. The Maya

artists achieved a sort of compromise between

appearance and reality. When they could not

find a way to correct a drawing, they at least

succeeded by graceful and pleasing treatment in

distracting attention from any errors in delinea-

tion.

The principal methods employed by the

Maya in the graphic and plastic arts differed

little from those of better known lands. Carving

in wood and stone and modeling in clay and

stucco were widely practiced. At the time from

which the remains of their art date they were

living, like the Mexicans, in an age of stone. The

elaborate monuments and temple decorations

were cut and carved with stone implements.

These people might have accomplished greater

wonders if they had had fine grained marble

instead of coarse, uneven limestone and iron or

bronze chisels instead of unwieldy stone knives.

The best achievements of the Maya are pre-

served on huge carved monolithic monuments, A WELL.PRESERVED SXELA AT QUIRICUA

commonly called stelae. These monster pil-

lars, approximately rectangular, usually pre-

sent a single figure, or one figure on the front

and another on the back, in addition to relief

carving, generally on all sides. The largest

of these are found in Quirigua but the art of

the neighboring site of Copan is the finer,

since many of the stelse here are carved in

such relief as to approximate the full round.

The exact purpose of these stela? is prob-

lematical. In the large majority of cases

they stand in relation to certain buildings

and are considered to be five-year count

markers known as Hotun. Many are found

with altars in front and appear to have been

connected with certain religious ceremonies.

A RICHLY SCULPTURED ALTAR AT COPAN

MARCH I925

Jour thirty-Jive