mceRriACionAL

think there can be too many roses, or that, as

roses, they matter. After all, we who look upon

his work and appraise it today are so very far

from being fin de siecle or from understanding the

impulses that moved the men of the nineties.

We do not feel the need for the perfume of deca-

dence to dissipate the mustiness of Victorianism.

But even were Conder alive today, he would still

be belittled because of the poetical quality of his

work. A poetic picture, as everyone knows, is a

little girl sitting in a field of flowers; or a sweet-

faced nun in a white habit, with hands folded in

prayer. The painting of fans of course is a mere

avocation; it has no purpose; it does not identify

the artist with this or that school of theorists.

And so, because his appropriate tag cannot be

found, he must go without the label of the artist.

In the last number of The Savoy, Arthur

Symonds—who had had to write most of it him-

self—wrote in his valedictory: "Comparatively

few people care for art at all, and most of these

care for it because they mistake it for something

else." Conder would probably have disagreed

with this. He found a great many people who

cared about art; people who scolded and encou-

raged him in his youth and admired and purchased

him in his maturity.

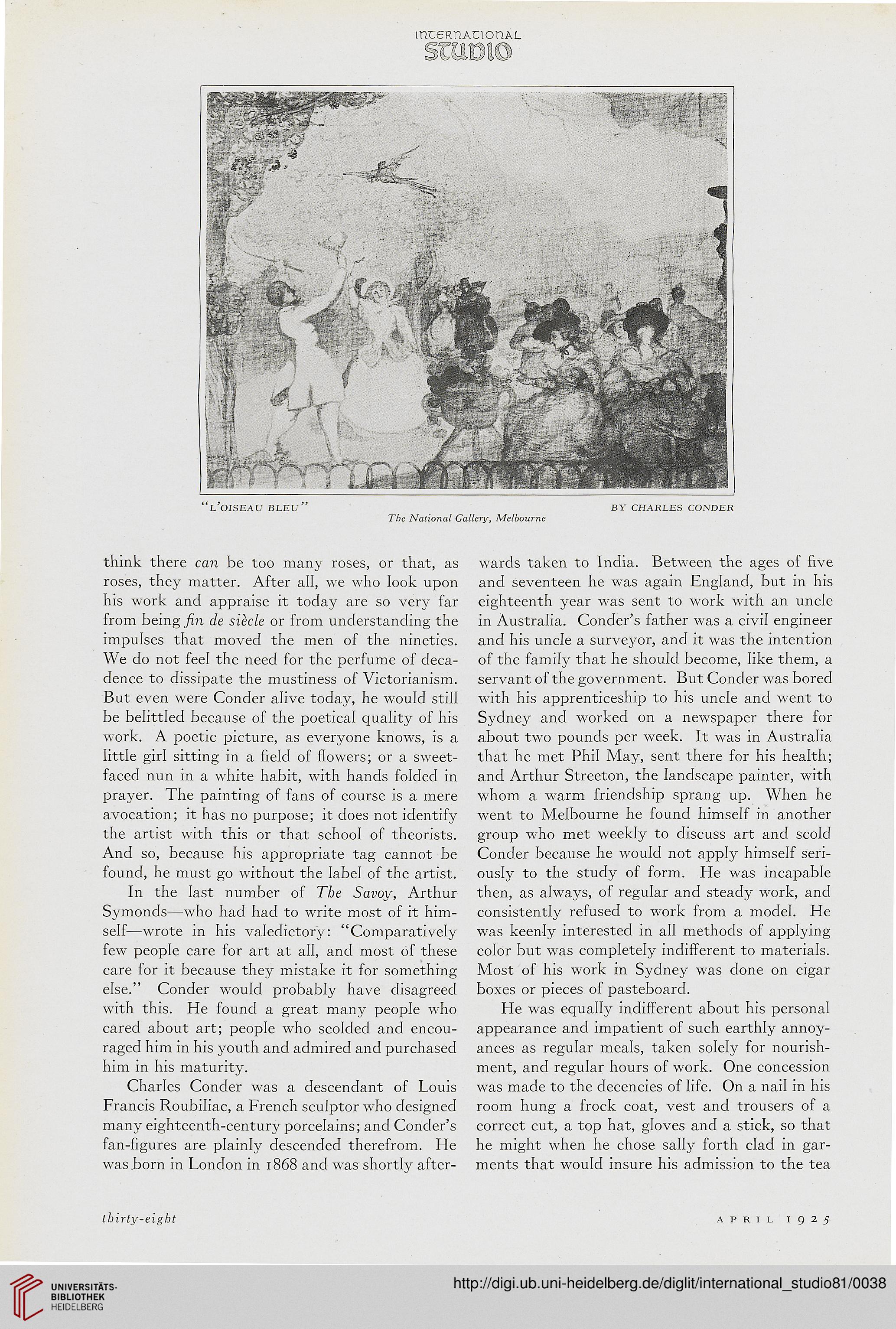

Charles Conder was a descendant of Louis

Francis Roubiliac, a French sculptor who designed

many eighteenth-century porcelains; and Conder's

fan-figures are plainly descended therefrom. He

was born in London in 1868 and was shortly after-

wards taken to India. Between the ages of five

and seventeen he was again England, but in his

eighteenth year was sent to work with an uncle

in Australia. Conder's father was a civil engineer

and his uncle a surveyor, and it was the intention

of the family that he should become, like them, a

servant of the government. But Conder was bored

with his apprenticeship to his uncle and went to

Sydney and worked on a newspaper there for

about two pounds per week. It was in Australia

that he met Phil May, sent there for his health;

and Arthur Streeton, the landscape painter, with

whom a warm friendship sprang up. When he

went to Melbourne he found himself in another

group who met weekly to discuss art and scold

Conder because he would not apply himself seri-

ously to the study of form. He was incapable

then, as always, of regular and steady work, and

consistently refused to work from a model. He

was keenly interested in all methods of applying

color but was completely indifferent to materials.

Most of his work in Sydney was done on cigar

boxes or pieces of pasteboard.

He was equally indifferent about his personal

appearance and impatient of such earthly annoy-

ances as regular meals, taken solely for nourish-

ment, and regular hours of work. One concession

was made to the decencies of life. On a nail in his

room hung a frock coat, vest and trousers of a

correct cut, a top hat, gloves and a stick, so that

he might when he chose sally forth clad in gar-

ments that would insure his admission to the tea

thirty-eight

APRIL I925

think there can be too many roses, or that, as

roses, they matter. After all, we who look upon

his work and appraise it today are so very far

from being fin de siecle or from understanding the

impulses that moved the men of the nineties.

We do not feel the need for the perfume of deca-

dence to dissipate the mustiness of Victorianism.

But even were Conder alive today, he would still

be belittled because of the poetical quality of his

work. A poetic picture, as everyone knows, is a

little girl sitting in a field of flowers; or a sweet-

faced nun in a white habit, with hands folded in

prayer. The painting of fans of course is a mere

avocation; it has no purpose; it does not identify

the artist with this or that school of theorists.

And so, because his appropriate tag cannot be

found, he must go without the label of the artist.

In the last number of The Savoy, Arthur

Symonds—who had had to write most of it him-

self—wrote in his valedictory: "Comparatively

few people care for art at all, and most of these

care for it because they mistake it for something

else." Conder would probably have disagreed

with this. He found a great many people who

cared about art; people who scolded and encou-

raged him in his youth and admired and purchased

him in his maturity.

Charles Conder was a descendant of Louis

Francis Roubiliac, a French sculptor who designed

many eighteenth-century porcelains; and Conder's

fan-figures are plainly descended therefrom. He

was born in London in 1868 and was shortly after-

wards taken to India. Between the ages of five

and seventeen he was again England, but in his

eighteenth year was sent to work with an uncle

in Australia. Conder's father was a civil engineer

and his uncle a surveyor, and it was the intention

of the family that he should become, like them, a

servant of the government. But Conder was bored

with his apprenticeship to his uncle and went to

Sydney and worked on a newspaper there for

about two pounds per week. It was in Australia

that he met Phil May, sent there for his health;

and Arthur Streeton, the landscape painter, with

whom a warm friendship sprang up. When he

went to Melbourne he found himself in another

group who met weekly to discuss art and scold

Conder because he would not apply himself seri-

ously to the study of form. He was incapable

then, as always, of regular and steady work, and

consistently refused to work from a model. He

was keenly interested in all methods of applying

color but was completely indifferent to materials.

Most of his work in Sydney was done on cigar

boxes or pieces of pasteboard.

He was equally indifferent about his personal

appearance and impatient of such earthly annoy-

ances as regular meals, taken solely for nourish-

ment, and regular hours of work. One concession

was made to the decencies of life. On a nail in his

room hung a frock coat, vest and trousers of a

correct cut, a top hat, gloves and a stick, so that

he might when he chose sally forth clad in gar-

ments that would insure his admission to the tea

thirty-eight

APRIL I925