ADVANTAGE OF TRADITION.

22 1

.showing different stages of growth. Among such, for the nude form are the

figures often called Apollo's, standing stiffly with the hands at the sides, or

with fore-arms raised ; for the draped, we have the seated figures of Miletos,

and the standing ones of Delos; and in relief, the most interesting series of

gravestones from Sparta.

This holding on to certain old types was, as we have seen, a peculiarity also

of Egyptian and Oriental sculpture; but the Greek, unlike his predecessors,

freely handled such types, and boldly made innovations and improvements

upon them. There can be little doubt, however, that this clinging to certain

given types in his formative stage had a most salutary effect in keeping him

within bounds, and in developing a well-disciplined school.

While the ancient sculptor's imagination was gradually unfolding, and his

hand was thus gaining in skill, he was, we must believe, greatly influenced by the

■_^***&mgm

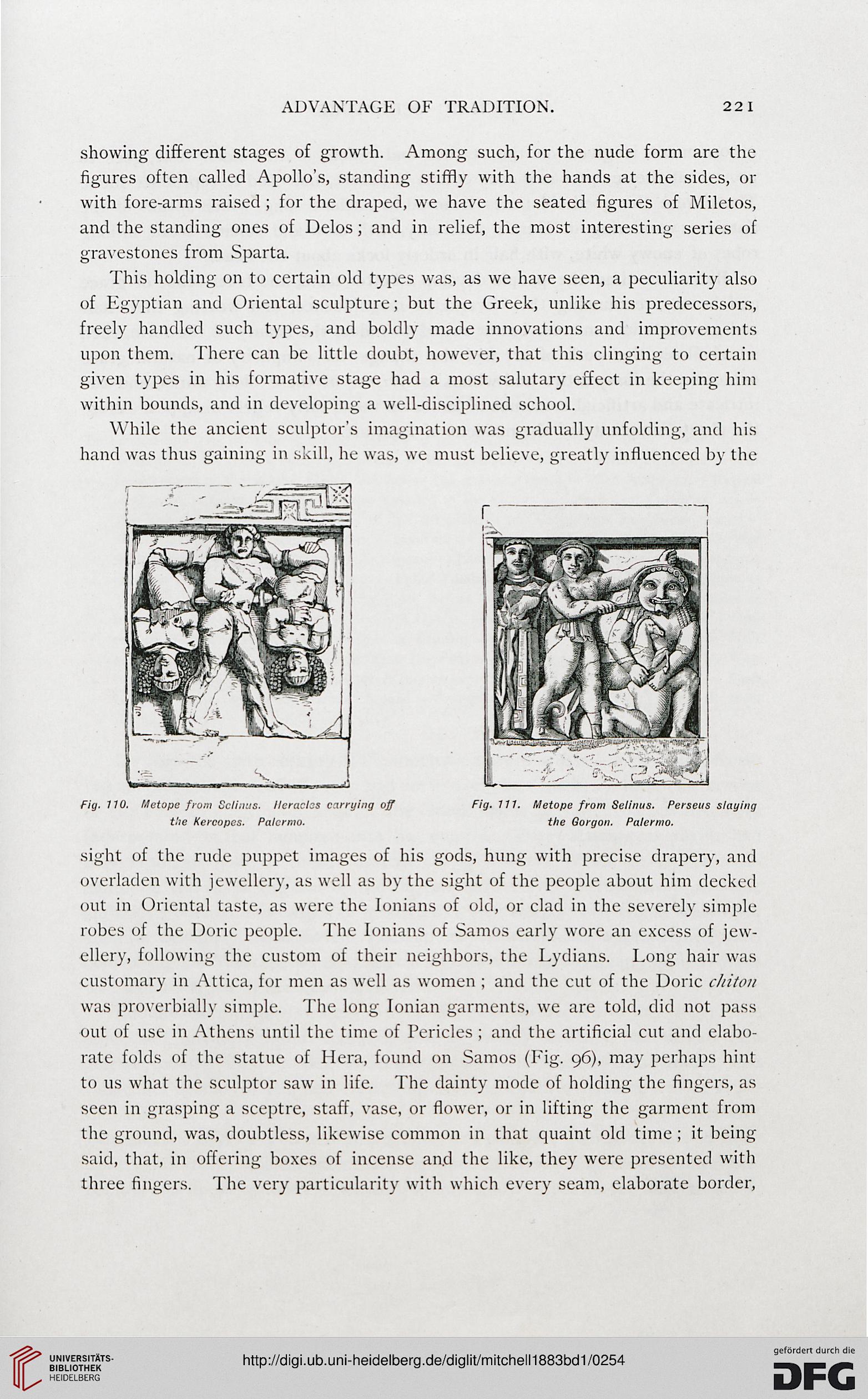

Fig. 110. Metope from Sclinus. Heracles carrying off

the Kercopes. Palermo.

Fig. 711. Metope from Selinus. Perseus slaying

the Gorgon. Palermo.

sight of the rude puppet images of his gods, hung with precise drapery, and

overladen with jeweller)', as well as by the sight of the people about him decked

out in Oriental taste, as were the Ionians of old, or clad in the severely simple

robes of the Doric people. The Ionians of Samos early wore an excess of jew-

ellery, following the custom of their neighbors, the Lydians. Long hair was

customary in Attica, for men as well as women ; and the cut of the Doric chiton

was proverbially simple. The long Ionian garments, we are told, did not pass

out of use in Athens until the time of Pericles ; and the artificial cut and elabo-

rate folds of the statue of Hera, found on Samos (Fig. 96), may perhaps hint

to us what the sculptor saw in life. The dainty mode of holding the fingers, as

seen in grasping a sceptre, staff, vase, or flower, or in lifting the garment from

the ground, was, doubtless, likewise common in that quaint old time ; it being

said, that, in offering boxes of incense and the like, they were presented with

three fingers. The very particularity with which every seam, elaborate border,

22 1

.showing different stages of growth. Among such, for the nude form are the

figures often called Apollo's, standing stiffly with the hands at the sides, or

with fore-arms raised ; for the draped, we have the seated figures of Miletos,

and the standing ones of Delos; and in relief, the most interesting series of

gravestones from Sparta.

This holding on to certain old types was, as we have seen, a peculiarity also

of Egyptian and Oriental sculpture; but the Greek, unlike his predecessors,

freely handled such types, and boldly made innovations and improvements

upon them. There can be little doubt, however, that this clinging to certain

given types in his formative stage had a most salutary effect in keeping him

within bounds, and in developing a well-disciplined school.

While the ancient sculptor's imagination was gradually unfolding, and his

hand was thus gaining in skill, he was, we must believe, greatly influenced by the

■_^***&mgm

Fig. 110. Metope from Sclinus. Heracles carrying off

the Kercopes. Palermo.

Fig. 711. Metope from Selinus. Perseus slaying

the Gorgon. Palermo.

sight of the rude puppet images of his gods, hung with precise drapery, and

overladen with jeweller)', as well as by the sight of the people about him decked

out in Oriental taste, as were the Ionians of old, or clad in the severely simple

robes of the Doric people. The Ionians of Samos early wore an excess of jew-

ellery, following the custom of their neighbors, the Lydians. Long hair was

customary in Attica, for men as well as women ; and the cut of the Doric chiton

was proverbially simple. The long Ionian garments, we are told, did not pass

out of use in Athens until the time of Pericles ; and the artificial cut and elabo-

rate folds of the statue of Hera, found on Samos (Fig. 96), may perhaps hint

to us what the sculptor saw in life. The dainty mode of holding the fingers, as

seen in grasping a sceptre, staff, vase, or flower, or in lifting the garment from

the ground, was, doubtless, likewise common in that quaint old time ; it being

said, that, in offering boxes of incense and the like, they were presented with

three fingers. The very particularity with which every seam, elaborate border,