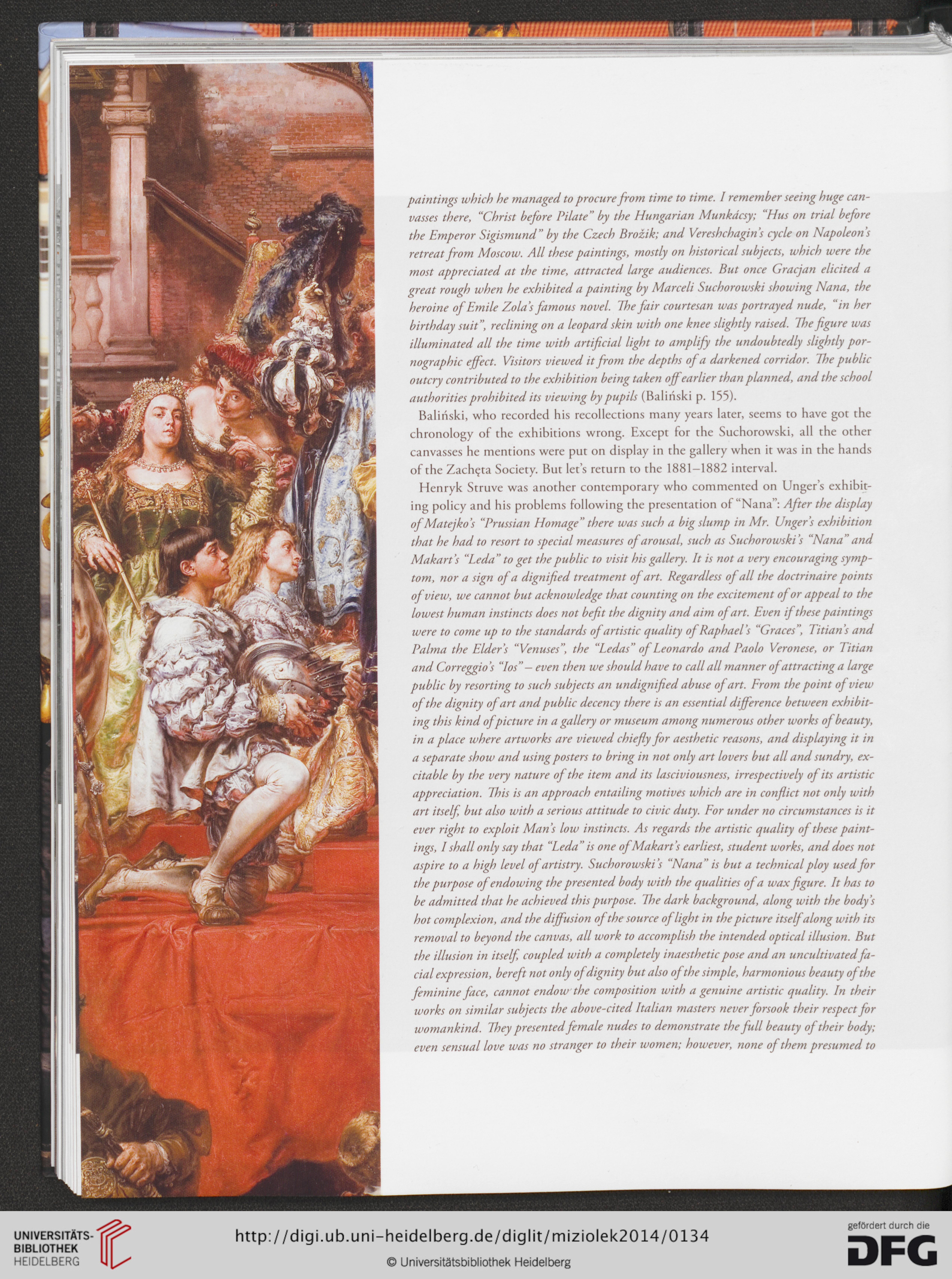

paintings which he managed to procurefrom time to time. I remember seeing huge can-

vasses there, “Christ before Pilate” by the Hungarian Munkdcsy; “Hus on trial before

the Emperor Sigismund” by the Czech Brozik; and Vereshchagin’s cycle on Napoleon’s

retreatfrom Moscow. All these paintings, mostly on historical subjects, which were the

most appreciated at the time, attracted large audiences. But once Gracjan elicited a

great rough when he exhibited a painting by Marceli Suchorowski showing Nana, the

heroine ofEmile Zola’s famous novel. The fair courtesan wasportrayed nude, “in her

birthday suit”, reclining on a leopard skin with one knee slightly raised. The figure was

illuminated all the time with artificial light to amplify the undoubtedly slightly por-

nographic ejfect. Visitors viewed it from the depths of a darkened corridor. The public

outcry contributed to the exhibition being taken ojf earlier than planned, and the school

authoritiesprohibited its viewing by pupils (Baliriski p. 155).

Baliriski, who recorded his recollections many years later, seems to have got the

chronology of the exhibitions wrong. Except for the Suchorowski, all the other

canvasses he mentions were put on display in the gallery when it was in the hands

of the Zach^ta Society. But let’s return to the 1881—1882 interval.

Henryk Struve was another contemporary who commented on Unger’s exhibit-

ing policy and his problems following the presentation of “Nana”: After the display

of Matejko’s “Prussian Homage” there was such a big slump in Mr. Unger’s exhibition

that he had to resort to special measures ofarousal, such as Suchorowski's “Nana”and

Makart’s “Leda” to get thepublic to visit his gallery. It is not a very encouraging symp-

tom, nor a sign ofa dignified treatment of art. Regardless ofall the doctrinaire points

ofview, we cannot but acknowledge that counting on the excitement of or appeal to the

lowest human instincts does not befit the dignity and aim ofart. Even ifthesepaintings

were to come up to the standards of artistic quality of Raphael's “Graces”, Titian’s and

Palma the Elder’s “Venuses”, the “Ledas” of Leonardo and Paolo Veronese, or Titian

and Correggio’s “Ios”— even then we should have to callall manner of attracting a large

public by resorting to such subjects an undignified abuse ofart. From the point of view

of the dignity ofart andpublic decency there is an essential dijference between exhibit-

ing this kind ofpicture in a gallery or museum among numerous other works ofbeauty,

in a place where artworks are viewed chiefly fior aesthetic reasons, and displaying it in

a separate show and usingposters to bring in not only art lovers but all and sundry, ex-

citable by the very nature ofthe item and its lasciviousness, irrespectively ofits artistic

appreciation. This is an approach entailing motives which are in conflict not only with

art itself, but also with a serious attitude to civic duty. For under no circumstances is it

ever right to exploit Man’s low instincts. As regards the artistic quality of these paint-

ings, Ishall only say that “Leda”is one ofMakart’s earliest, student works, anddoes not

aspire to a high level of artistry. Suchorowski’s “Nana” is but a technicalploy usedfor

the purpose of endowing the presented body with the qualities ofa waxfigure. It has to

be admitted that he achieved thispurpose. The dark background, along with the body’s

hot complexion, and the diffusion of the source oflight in thepicture itself along with its

removal to beyond the canvas, all work to accomplish the intended optical illusion. But

the illusion in itself, coupled with a completely inaestheticpose and an uncultivatedfa-

cial expression, bereft not only of dignity but also of the simple, harmonious beauty ofthe

feminine face, cannot endow the composition with a genuine artistic quality. In their

works on similar subjects the above-cited Italian masters never forsook their respect for

womankind. They presentedfemale nudes to demonstrate the full beauty oftheir body;

even sensual love was no stranger to their women; however, none ofthem presumed to

vasses there, “Christ before Pilate” by the Hungarian Munkdcsy; “Hus on trial before

the Emperor Sigismund” by the Czech Brozik; and Vereshchagin’s cycle on Napoleon’s

retreatfrom Moscow. All these paintings, mostly on historical subjects, which were the

most appreciated at the time, attracted large audiences. But once Gracjan elicited a

great rough when he exhibited a painting by Marceli Suchorowski showing Nana, the

heroine ofEmile Zola’s famous novel. The fair courtesan wasportrayed nude, “in her

birthday suit”, reclining on a leopard skin with one knee slightly raised. The figure was

illuminated all the time with artificial light to amplify the undoubtedly slightly por-

nographic ejfect. Visitors viewed it from the depths of a darkened corridor. The public

outcry contributed to the exhibition being taken ojf earlier than planned, and the school

authoritiesprohibited its viewing by pupils (Baliriski p. 155).

Baliriski, who recorded his recollections many years later, seems to have got the

chronology of the exhibitions wrong. Except for the Suchorowski, all the other

canvasses he mentions were put on display in the gallery when it was in the hands

of the Zach^ta Society. But let’s return to the 1881—1882 interval.

Henryk Struve was another contemporary who commented on Unger’s exhibit-

ing policy and his problems following the presentation of “Nana”: After the display

of Matejko’s “Prussian Homage” there was such a big slump in Mr. Unger’s exhibition

that he had to resort to special measures ofarousal, such as Suchorowski's “Nana”and

Makart’s “Leda” to get thepublic to visit his gallery. It is not a very encouraging symp-

tom, nor a sign ofa dignified treatment of art. Regardless ofall the doctrinaire points

ofview, we cannot but acknowledge that counting on the excitement of or appeal to the

lowest human instincts does not befit the dignity and aim ofart. Even ifthesepaintings

were to come up to the standards of artistic quality of Raphael's “Graces”, Titian’s and

Palma the Elder’s “Venuses”, the “Ledas” of Leonardo and Paolo Veronese, or Titian

and Correggio’s “Ios”— even then we should have to callall manner of attracting a large

public by resorting to such subjects an undignified abuse ofart. From the point of view

of the dignity ofart andpublic decency there is an essential dijference between exhibit-

ing this kind ofpicture in a gallery or museum among numerous other works ofbeauty,

in a place where artworks are viewed chiefly fior aesthetic reasons, and displaying it in

a separate show and usingposters to bring in not only art lovers but all and sundry, ex-

citable by the very nature ofthe item and its lasciviousness, irrespectively ofits artistic

appreciation. This is an approach entailing motives which are in conflict not only with

art itself, but also with a serious attitude to civic duty. For under no circumstances is it

ever right to exploit Man’s low instincts. As regards the artistic quality of these paint-

ings, Ishall only say that “Leda”is one ofMakart’s earliest, student works, anddoes not

aspire to a high level of artistry. Suchorowski’s “Nana” is but a technicalploy usedfor

the purpose of endowing the presented body with the qualities ofa waxfigure. It has to

be admitted that he achieved thispurpose. The dark background, along with the body’s

hot complexion, and the diffusion of the source oflight in thepicture itself along with its

removal to beyond the canvas, all work to accomplish the intended optical illusion. But

the illusion in itself, coupled with a completely inaestheticpose and an uncultivatedfa-

cial expression, bereft not only of dignity but also of the simple, harmonious beauty ofthe

feminine face, cannot endow the composition with a genuine artistic quality. In their

works on similar subjects the above-cited Italian masters never forsook their respect for

womankind. They presentedfemale nudes to demonstrate the full beauty oftheir body;

even sensual love was no stranger to their women; however, none ofthem presumed to