i8o

PLASTIC VASES

Acheloos-heads: debased, but apparently early, versions of a regular Ionian type; see

Maximova p. 163, and add one in Oxford (C.V.A. fasc. ii).

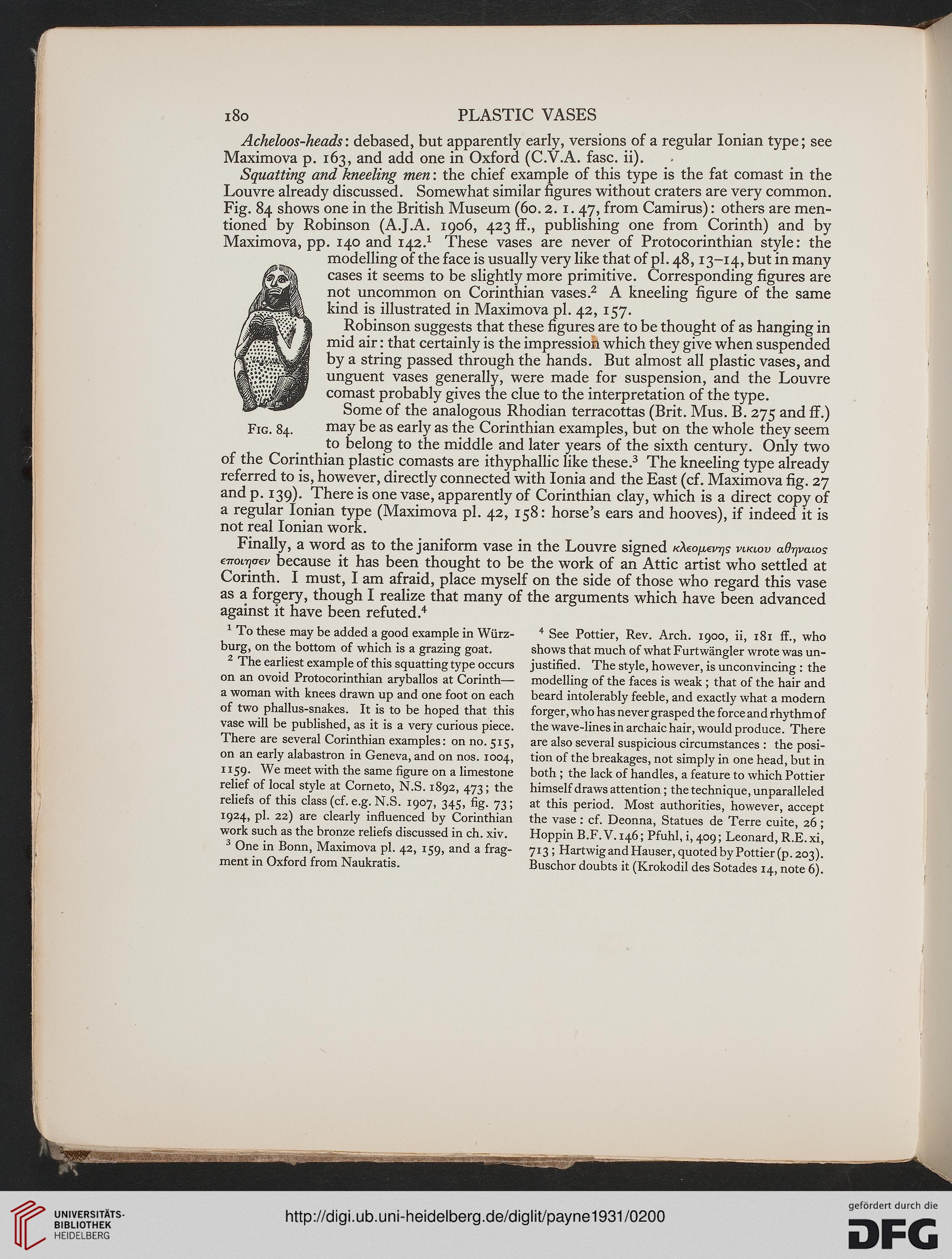

Squatting and kneeling men: the chief example of this type is the fat comast in the

Louvre already discussed. Somewhat similar figures without craters are very common.

Fig. 84 shows one in the British Museum (60.2. 1. 47, from Camirus): others are men-

tioned by Robinson (A.J.A. 1906, 423 ff., publishing one from Corinth) and by

Maximova, pp. 140 and 142.1 These vases are never of Protocorinthian style: the

modelling of the face is usually very like that of pi. 48,13-14, but in many

cases it seems to be slightly more primitive. Corresponding figures are

not uncommon on Corinthian vases.2 A kneeling figure of the same

kind is illustrated in Maximova pi. 42, 157.

Robinson suggests that these figures are to be thought of as hanging in

mid air: that certainly is the impression which they give when suspended

by a string passed through the hands. But almost all plastic vases, and

unguent vases generally, were made for suspension, and the Louvre

comast probably gives the clue to the interpretation of the type.

Some of the analogous Rhodian terracottas (Brit. Mus. B. 275 and ff.)

may be as early as the Corinthian examples, but on the whole they seem

to belong to the middle and later years of the sixth century. Only two

of the Corinthian plastic comasts are ithyphallic like these.3 The kneeling type already

referred to is, however, directly connected with Ionia and the East (cf. Maximova fig. 27

and p. 139). There is one vase, apparently of Corinthian clay, which is a direct copy of

a regular Ionian type (Maximova pi. 42, 158: horse's ears and hooves), if indeed it is

not real Ionian work.

Finally, a word as to the janiform vase in the Louvre signed /cAeo/nev^? vlklov aOrjvaios

eTTOL-qaev because it has been thought to be the work of an Attic artist who settled at

Corinth. I must, I am afraid, place myself on the side of those who regard this vase

as a forgery, though I realize that many of the arguments which have been advanced

against it have been refuted.4

Fig. 84.

1 To these may be added a good example in Wiirz-

burg, on the bottom of which is a grazing goat.

2 The earliest example of this squatting type occurs

on an ovoid Protocorinthian aryballos at Corinth—

a woman with knees drawn up and one foot on each

of two phallus-snakes. It is to be hoped that this

vase will be published, as it is a very curious piece.

There are several Corinthian examples: on no. 515,

on an early alabastron in Geneva, and on nos. 1004,

1159. We meet with the same figure on a limestone

relief of local style at Corneto, N.S. 1892, 473; the

reliefs of this class (cf. e.g. N.S. 1907, 345, fig. 73;

1924, pi. 22) are clearly influenced by Corinthian

work such as the bronze reliefs discussed in ch. xiv.

3 One in Bonn, Maximova pi. 42, 159, and a frag-

ment in Oxford from Naukratis.

4 See Pottier, Rev. Arch. 1900, ii, 181 ff., who

shows that much of what Furtwangler wrote was un-

justified. The style, however, is unconvincing : the

modelling of the faces is weak ; that of the hair and

beard intolerably feeble, and exactly what a modern

forger, who has never grasped the force and rhythm of

the wave-lines in archaic hair, would produce. There

are also several suspicious circumstances : the posi-

tion of the breakages, not simply in one head, but in

both ; the lack of handles, a feature to which Pottier

himself draws attention; the technique, unparalleled

at this period. Most authorities, however, accept

the vase : cf. Deonna, Statues de Terre cuite, 26;

Hoppin B.F.V.146; Pfuhl, i, 409; Leonard, R.E.xi,

713 ; HartwigandHauser, quoted by Pottier (p. 203).

Buschor doubts it (Krokodil des Sotades 14, note 6).

PLASTIC VASES

Acheloos-heads: debased, but apparently early, versions of a regular Ionian type; see

Maximova p. 163, and add one in Oxford (C.V.A. fasc. ii).

Squatting and kneeling men: the chief example of this type is the fat comast in the

Louvre already discussed. Somewhat similar figures without craters are very common.

Fig. 84 shows one in the British Museum (60.2. 1. 47, from Camirus): others are men-

tioned by Robinson (A.J.A. 1906, 423 ff., publishing one from Corinth) and by

Maximova, pp. 140 and 142.1 These vases are never of Protocorinthian style: the

modelling of the face is usually very like that of pi. 48,13-14, but in many

cases it seems to be slightly more primitive. Corresponding figures are

not uncommon on Corinthian vases.2 A kneeling figure of the same

kind is illustrated in Maximova pi. 42, 157.

Robinson suggests that these figures are to be thought of as hanging in

mid air: that certainly is the impression which they give when suspended

by a string passed through the hands. But almost all plastic vases, and

unguent vases generally, were made for suspension, and the Louvre

comast probably gives the clue to the interpretation of the type.

Some of the analogous Rhodian terracottas (Brit. Mus. B. 275 and ff.)

may be as early as the Corinthian examples, but on the whole they seem

to belong to the middle and later years of the sixth century. Only two

of the Corinthian plastic comasts are ithyphallic like these.3 The kneeling type already

referred to is, however, directly connected with Ionia and the East (cf. Maximova fig. 27

and p. 139). There is one vase, apparently of Corinthian clay, which is a direct copy of

a regular Ionian type (Maximova pi. 42, 158: horse's ears and hooves), if indeed it is

not real Ionian work.

Finally, a word as to the janiform vase in the Louvre signed /cAeo/nev^? vlklov aOrjvaios

eTTOL-qaev because it has been thought to be the work of an Attic artist who settled at

Corinth. I must, I am afraid, place myself on the side of those who regard this vase

as a forgery, though I realize that many of the arguments which have been advanced

against it have been refuted.4

Fig. 84.

1 To these may be added a good example in Wiirz-

burg, on the bottom of which is a grazing goat.

2 The earliest example of this squatting type occurs

on an ovoid Protocorinthian aryballos at Corinth—

a woman with knees drawn up and one foot on each

of two phallus-snakes. It is to be hoped that this

vase will be published, as it is a very curious piece.

There are several Corinthian examples: on no. 515,

on an early alabastron in Geneva, and on nos. 1004,

1159. We meet with the same figure on a limestone

relief of local style at Corneto, N.S. 1892, 473; the

reliefs of this class (cf. e.g. N.S. 1907, 345, fig. 73;

1924, pi. 22) are clearly influenced by Corinthian

work such as the bronze reliefs discussed in ch. xiv.

3 One in Bonn, Maximova pi. 42, 159, and a frag-

ment in Oxford from Naukratis.

4 See Pottier, Rev. Arch. 1900, ii, 181 ff., who

shows that much of what Furtwangler wrote was un-

justified. The style, however, is unconvincing : the

modelling of the faces is weak ; that of the hair and

beard intolerably feeble, and exactly what a modern

forger, who has never grasped the force and rhythm of

the wave-lines in archaic hair, would produce. There

are also several suspicious circumstances : the posi-

tion of the breakages, not simply in one head, but in

both ; the lack of handles, a feature to which Pottier

himself draws attention; the technique, unparalleled

at this period. Most authorities, however, accept

the vase : cf. Deonna, Statues de Terre cuite, 26;

Hoppin B.F.V.146; Pfuhl, i, 409; Leonard, R.E.xi,

713 ; HartwigandHauser, quoted by Pottier (p. 203).

Buschor doubts it (Krokodil des Sotades 14, note 6).