6

PREFACE.

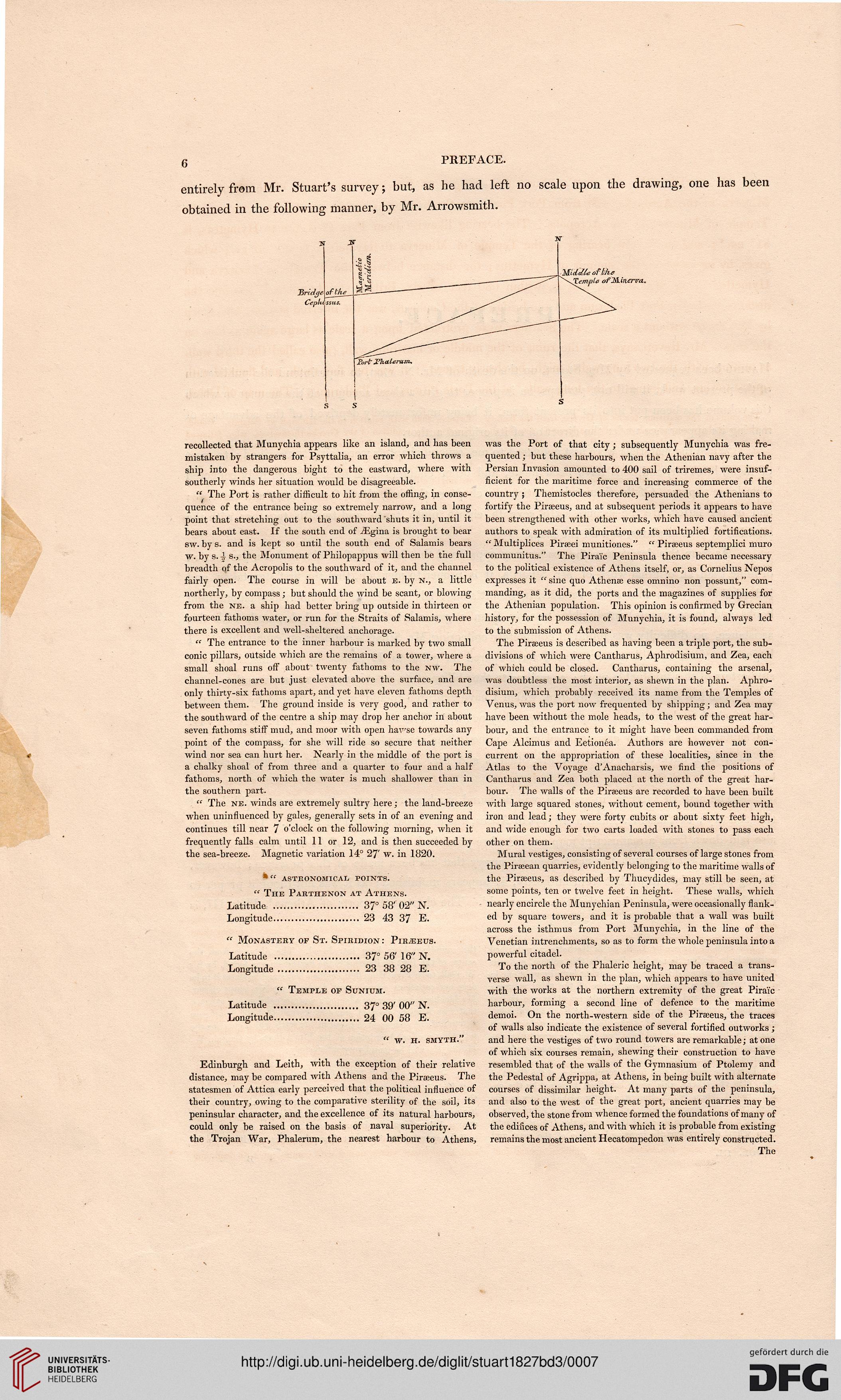

entirely from Mr. Stuart's survey; but, as he had left no scale upon the drawing, one has been

obtained in the following manner, by Mr. Arrowsmith.

AT

Middle of the

Tem/ile of Minerva.

recollected that Munychia appears like an island, and has been

mistaken by strangers for Psyttalia, an error which throws a

ship into the dangerous bight to the eastward, where with

southerly winds her situation would be disagreeable.

" The Port is rather difficult to hit from the offing, in conse-

quence of the entrance being so extremely narrow, and a long

point that stretching out to the southward "shuts it in, until it

bears about east. If the south end of iEgina is brought to bear

sw. by s. and is kept so until the south end of Salamis bears

w. by s. 4 s., the Monument of Philopappus will then be the full

breadth of the Acropolis to the southward of it, and the channel

fairly open. The course in will be about B. by n., a little

northerly, by compass; but should the wind be scant, or blowing

from the ne. a ship had better bring up outside in thirteen or

fourteen fathoms water, or run for the Straits of Salamis, where

there is excellent and well-sheltered anchorage.

" The entrance to the inner harbour is marked by two small

conic pillars, outside which are the remains of a tower, where a

small shoal runs off about twenty fathoms to the nw. The

channel-cones are but just elevated above the surface, and are

only thirty-six fathoms apart, and yet have eleven fathoms depth

between them. The ground inside is very good, and rather to

the southward of the centre a ship may drop her anchor in about

seven fathoms stiff mud, and moor witli open havse towards any

point of the compass, for she will ride so secure that neither

wind nor sea can hurt her. Nearly in the middle of the port is

a chalky shoal of from three and a quarter to four and a half

fathoms, north of which the water is much shallower than in

the southern part.

" The ne. winds are extremely sultry here; the land-breeze

when uninfluenced by gales, generally sets in of an evening and

continues till near 7 o'clock on the following morning, when it

frequently falls calm until 11 or 12, and is then succeeded by

the sea-breeze. Magnetic variation 14° 27' w. in 1820.

*" astronomical points.

" The Parthenon at Athens.

Latitude ........................ 37° 58'02" N.

Longitude........................ 23 43 37 E.

" Monastery op St. Spiridion : Piraeus.

Latitude ........................ 37° 56'16" N.

Longitude ....................... 23 38 28 E.

*' Temple of Sunium.

Latitude ........................ 37° 39'00" N.

Longitude........................ 24 00 58 E.

" W. H. SMYTH."

Edinburgh and Leith, with the exception of their relative

distance, may be compared with Athens and the Piraeus. The

statesmen of Attica early perceived that the political influence of

their country, owing to the comparative sterility of the soil, its

peninsular character, and the excellence of its natural harbours,

could only be raised on the basis of naval superiority. At

the Trojan War, Phalerum, the nearest harbour to Athens,

was the Port of that city; subsequently Munychia was fre-

quented ; but these harbours, when the Athenian navy after the

Persian Invasion amounted to 400 sail of triremes, were insuf-

ficient for the maritime force and increasing commerce of the

country ; Themistocles therefore, persuaded the Athenians to

fortify the Piraeus, and at subsequent periods it appears to have

been strengthened with other works, which have caused ancient

authors to speak with admiration of its multiplied fortifications.

" Multiplices Piraeei munitiones." " Piraeus septemplici muro

communitus." The PiraYc Peninsula thence became necessary

to the political existence of Athens itself, or, as Cornelius Nepos

expresses it " sine quo Athense esse omnino non possunt," com-

manding, as it did, the ports and the magazines of supplies for

the Athenian population. This opinion is confirmed by Grecian

history, for the possession of Munychia, it is found, always led

to the submission of Athens.

The Piraeus is described as having been a triple port, the sub-

divisions of which were Cantharus, Aphrodisium, and Zea, each

of which could be closed. Cantharus, containing the arsenal,

was doubtless the most interior, as shewn in the plan. Aphro-

disium, which probably received its name from the Temples of

Venus, was the port now frequented by shipping; and Zea may

have been without the mole heads, to the west of the great har-

bour, and the entrance to it might have been commanded from

Cape Alcimus and I^etionea. Authors are however not con-

current on the appropriation of these localities, since in the

Atlas to the Voyage d'Anacharsis, we find the positions of

Cantharus and Zea both placed at the north of the great har-

bour. The walls of the Piraeus arc recorded to have been built

with large squared stones, without cement, bound together with

iron and lead; they were forty cubits or about sixty feet high,

and wide enough for two carts loaded with stones to pass each

other on them.

Mural vestiges, consisting of several courses of large stones from

the Piraeean quarries, evidently belonging to the maritime walls of

the Piraeus, as described by Thucydides, may still be seen, at

some points, ten or twelve feet in height. These walls, which

nearly encircle the Munychian Peninsula, were occasionally flank-

ed by square towers, and it is probable that a wall was built

across the isthmus from Port Munychia, in the line of the

Venetian intrenchments, so as to form the whole peninsula into a

powerful citadel.

To the north of the Phaleric height, may be traced a trans-

verse wall, as shewn in the plan, which appears to have united

with the works at the northern extremity of the great Pirai'c

harbour, forming a second line of defence to the maritime

demoi. On the north-western side of the Piraeus, the traces

of walls also indicate the existence of several fortified outworks;

and here the vestiges of two round towers are remarkable: at one

of which six courses remain, shewing their construction to have

resembled that of the walls of the Gymnasium of Ptolemy and

the Pedestal of Agrippa, at Athens, in being built with alternate

courses of dissimilar height. At many parts of the peninsula,

and also to the west of the great port, ancient quarries may be

observed, the stone from whence formed the foundations of many of

the edifices of Athens, and with which it is probable from existing

remains the most ancient Hecatompedon was entirely constructed.

The

PREFACE.

entirely from Mr. Stuart's survey; but, as he had left no scale upon the drawing, one has been

obtained in the following manner, by Mr. Arrowsmith.

AT

Middle of the

Tem/ile of Minerva.

recollected that Munychia appears like an island, and has been

mistaken by strangers for Psyttalia, an error which throws a

ship into the dangerous bight to the eastward, where with

southerly winds her situation would be disagreeable.

" The Port is rather difficult to hit from the offing, in conse-

quence of the entrance being so extremely narrow, and a long

point that stretching out to the southward "shuts it in, until it

bears about east. If the south end of iEgina is brought to bear

sw. by s. and is kept so until the south end of Salamis bears

w. by s. 4 s., the Monument of Philopappus will then be the full

breadth of the Acropolis to the southward of it, and the channel

fairly open. The course in will be about B. by n., a little

northerly, by compass; but should the wind be scant, or blowing

from the ne. a ship had better bring up outside in thirteen or

fourteen fathoms water, or run for the Straits of Salamis, where

there is excellent and well-sheltered anchorage.

" The entrance to the inner harbour is marked by two small

conic pillars, outside which are the remains of a tower, where a

small shoal runs off about twenty fathoms to the nw. The

channel-cones are but just elevated above the surface, and are

only thirty-six fathoms apart, and yet have eleven fathoms depth

between them. The ground inside is very good, and rather to

the southward of the centre a ship may drop her anchor in about

seven fathoms stiff mud, and moor witli open havse towards any

point of the compass, for she will ride so secure that neither

wind nor sea can hurt her. Nearly in the middle of the port is

a chalky shoal of from three and a quarter to four and a half

fathoms, north of which the water is much shallower than in

the southern part.

" The ne. winds are extremely sultry here; the land-breeze

when uninfluenced by gales, generally sets in of an evening and

continues till near 7 o'clock on the following morning, when it

frequently falls calm until 11 or 12, and is then succeeded by

the sea-breeze. Magnetic variation 14° 27' w. in 1820.

*" astronomical points.

" The Parthenon at Athens.

Latitude ........................ 37° 58'02" N.

Longitude........................ 23 43 37 E.

" Monastery op St. Spiridion : Piraeus.

Latitude ........................ 37° 56'16" N.

Longitude ....................... 23 38 28 E.

*' Temple of Sunium.

Latitude ........................ 37° 39'00" N.

Longitude........................ 24 00 58 E.

" W. H. SMYTH."

Edinburgh and Leith, with the exception of their relative

distance, may be compared with Athens and the Piraeus. The

statesmen of Attica early perceived that the political influence of

their country, owing to the comparative sterility of the soil, its

peninsular character, and the excellence of its natural harbours,

could only be raised on the basis of naval superiority. At

the Trojan War, Phalerum, the nearest harbour to Athens,

was the Port of that city; subsequently Munychia was fre-

quented ; but these harbours, when the Athenian navy after the

Persian Invasion amounted to 400 sail of triremes, were insuf-

ficient for the maritime force and increasing commerce of the

country ; Themistocles therefore, persuaded the Athenians to

fortify the Piraeus, and at subsequent periods it appears to have

been strengthened with other works, which have caused ancient

authors to speak with admiration of its multiplied fortifications.

" Multiplices Piraeei munitiones." " Piraeus septemplici muro

communitus." The PiraYc Peninsula thence became necessary

to the political existence of Athens itself, or, as Cornelius Nepos

expresses it " sine quo Athense esse omnino non possunt," com-

manding, as it did, the ports and the magazines of supplies for

the Athenian population. This opinion is confirmed by Grecian

history, for the possession of Munychia, it is found, always led

to the submission of Athens.

The Piraeus is described as having been a triple port, the sub-

divisions of which were Cantharus, Aphrodisium, and Zea, each

of which could be closed. Cantharus, containing the arsenal,

was doubtless the most interior, as shewn in the plan. Aphro-

disium, which probably received its name from the Temples of

Venus, was the port now frequented by shipping; and Zea may

have been without the mole heads, to the west of the great har-

bour, and the entrance to it might have been commanded from

Cape Alcimus and I^etionea. Authors are however not con-

current on the appropriation of these localities, since in the

Atlas to the Voyage d'Anacharsis, we find the positions of

Cantharus and Zea both placed at the north of the great har-

bour. The walls of the Piraeus arc recorded to have been built

with large squared stones, without cement, bound together with

iron and lead; they were forty cubits or about sixty feet high,

and wide enough for two carts loaded with stones to pass each

other on them.

Mural vestiges, consisting of several courses of large stones from

the Piraeean quarries, evidently belonging to the maritime walls of

the Piraeus, as described by Thucydides, may still be seen, at

some points, ten or twelve feet in height. These walls, which

nearly encircle the Munychian Peninsula, were occasionally flank-

ed by square towers, and it is probable that a wall was built

across the isthmus from Port Munychia, in the line of the

Venetian intrenchments, so as to form the whole peninsula into a

powerful citadel.

To the north of the Phaleric height, may be traced a trans-

verse wall, as shewn in the plan, which appears to have united

with the works at the northern extremity of the great Pirai'c

harbour, forming a second line of defence to the maritime

demoi. On the north-western side of the Piraeus, the traces

of walls also indicate the existence of several fortified outworks;

and here the vestiges of two round towers are remarkable: at one

of which six courses remain, shewing their construction to have

resembled that of the walls of the Gymnasium of Ptolemy and

the Pedestal of Agrippa, at Athens, in being built with alternate

courses of dissimilar height. At many parts of the peninsula,

and also to the west of the great port, ancient quarries may be

observed, the stone from whence formed the foundations of many of

the edifices of Athens, and with which it is probable from existing

remains the most ancient Hecatompedon was entirely constructed.

The