Hispano-Moresque Lustre IVare

on No. 13 yet been identified. No. 9 displays a

wyvern ; while No. 14, a lion rampant holding in

his dexter paw a fleur-de-lys, probably represents

some Italian family, notwithstanding the shield

itself is not of Italian shape.

Among other examples not yet referred to, five

comprise representations of various birds, which,

not being charged upon shields, are to be regarded

as decorative rather than heraldic. Nos. 2 and 5,

the former adorned with a fine rendering of a raven,

are both early examples, dating from the first

quarter of the fifteenth century. Nos. 15 and 23

depict birds more nearly like pigeons than any

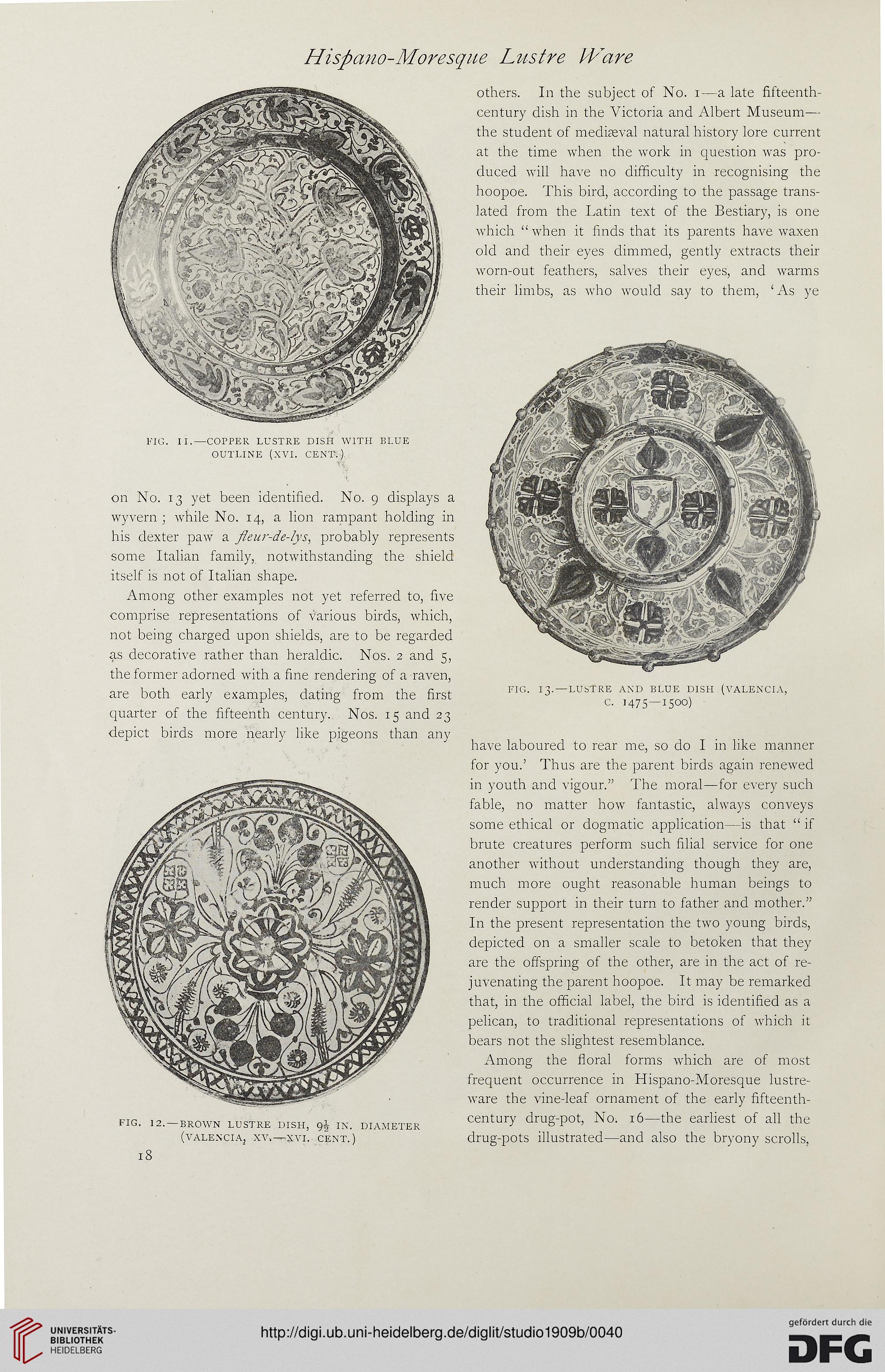

FIG. 12. —BROWN LUSTRE DISH, IN. DIAMETER

(VALENCIA, XV-.—-XVI. CENT.)

others. In the subject of No. i—a late fifteenth-

century dish in the Victoria and Albert Museum—

the student of mediaeval natural history lore current

at the time when the work in question was pro-

duced will have no difficulty in recognising the

hoopoe. This bird, according to the passage trans-

lated from the Latin text of the Bestiary, is one

which “when it finds that its parents have waxen

old and their eyes dimmed, gently extracts their

worn-out feathers, salves their eyes, and warms

their limbs, as who would say to them, ‘As ye

FIG. 13. —LUSTRE AND BLUE DISH (VALENCIA,

c. 1475—1500)

have laboured to rear me, so do I in like manner

for you.’ Thus are the parent birds again renewed

in youth and vigour.” The moral—for every such

fable, no matter how fantastic, always conveys

some ethical or dogmatic application—is that “ if

brute creatures perform such filial service for one

another without understanding though they are,

much more ought reasonable human beings to

render support in their turn to father and mother.”

In the present representation the two young birds,

depicted on a smaller scale to betoken that they

are the offspring of the other, are in the act of re-

juvenating the parent hoopoe. It may be remarked

that, in the official label, the bird is identified as a

pelican, to traditional representations of which it

bears not the slightest resemblance.

Among the floral forms which are of most

frequent occurrence in Hispano-Moresque lustre-

ware the vine-leaf ornament of the early fifteenth-

century drug-pot, No. 16—the earliest of all the

drug-pots illustrated—and also the bryony scrolls,

on No. 13 yet been identified. No. 9 displays a

wyvern ; while No. 14, a lion rampant holding in

his dexter paw a fleur-de-lys, probably represents

some Italian family, notwithstanding the shield

itself is not of Italian shape.

Among other examples not yet referred to, five

comprise representations of various birds, which,

not being charged upon shields, are to be regarded

as decorative rather than heraldic. Nos. 2 and 5,

the former adorned with a fine rendering of a raven,

are both early examples, dating from the first

quarter of the fifteenth century. Nos. 15 and 23

depict birds more nearly like pigeons than any

FIG. 12. —BROWN LUSTRE DISH, IN. DIAMETER

(VALENCIA, XV-.—-XVI. CENT.)

others. In the subject of No. i—a late fifteenth-

century dish in the Victoria and Albert Museum—

the student of mediaeval natural history lore current

at the time when the work in question was pro-

duced will have no difficulty in recognising the

hoopoe. This bird, according to the passage trans-

lated from the Latin text of the Bestiary, is one

which “when it finds that its parents have waxen

old and their eyes dimmed, gently extracts their

worn-out feathers, salves their eyes, and warms

their limbs, as who would say to them, ‘As ye

FIG. 13. —LUSTRE AND BLUE DISH (VALENCIA,

c. 1475—1500)

have laboured to rear me, so do I in like manner

for you.’ Thus are the parent birds again renewed

in youth and vigour.” The moral—for every such

fable, no matter how fantastic, always conveys

some ethical or dogmatic application—is that “ if

brute creatures perform such filial service for one

another without understanding though they are,

much more ought reasonable human beings to

render support in their turn to father and mother.”

In the present representation the two young birds,

depicted on a smaller scale to betoken that they

are the offspring of the other, are in the act of re-

juvenating the parent hoopoe. It may be remarked

that, in the official label, the bird is identified as a

pelican, to traditional representations of which it

bears not the slightest resemblance.

Among the floral forms which are of most

frequent occurrence in Hispano-Moresque lustre-

ware the vine-leaf ornament of the early fifteenth-

century drug-pot, No. 16—the earliest of all the

drug-pots illustrated—and also the bryony scrolls,