Modern Interior Painting

In the old Dutch interior paintings, in their still

life paintings—for these two go together—we feel

the pleasure which the painters took in each little

incident they painted. How they loved to make

everything so very real though all on a doll’s house

scale. They were like children with a doll’s house.

It has significance, perhaps, that the present return

to all this interior incident began in Mr. William

Rothenstein’s The Doll's House. Mr. Rothenstein

had to go on to other things, for a true artist

scarcely directs himself. Perhaps Mr. Orpen has

expressed himself best in interior painting, because

of his pleasure in glasses and picture frames, in

papers and trays, in sunny spaces of wall and

bright things shining from the shadows, in the

curiously pale and rainbow gleams of old porce-

lain—and above all, because his art is so evidently

the expression of his pleasure in these things, his

and their owner’s—for he paints the portraits of

collectors, I believe, for the sake of their collections.

He has shown this pleasure in art which is also

expressive of the purest pleasures of painting itself.

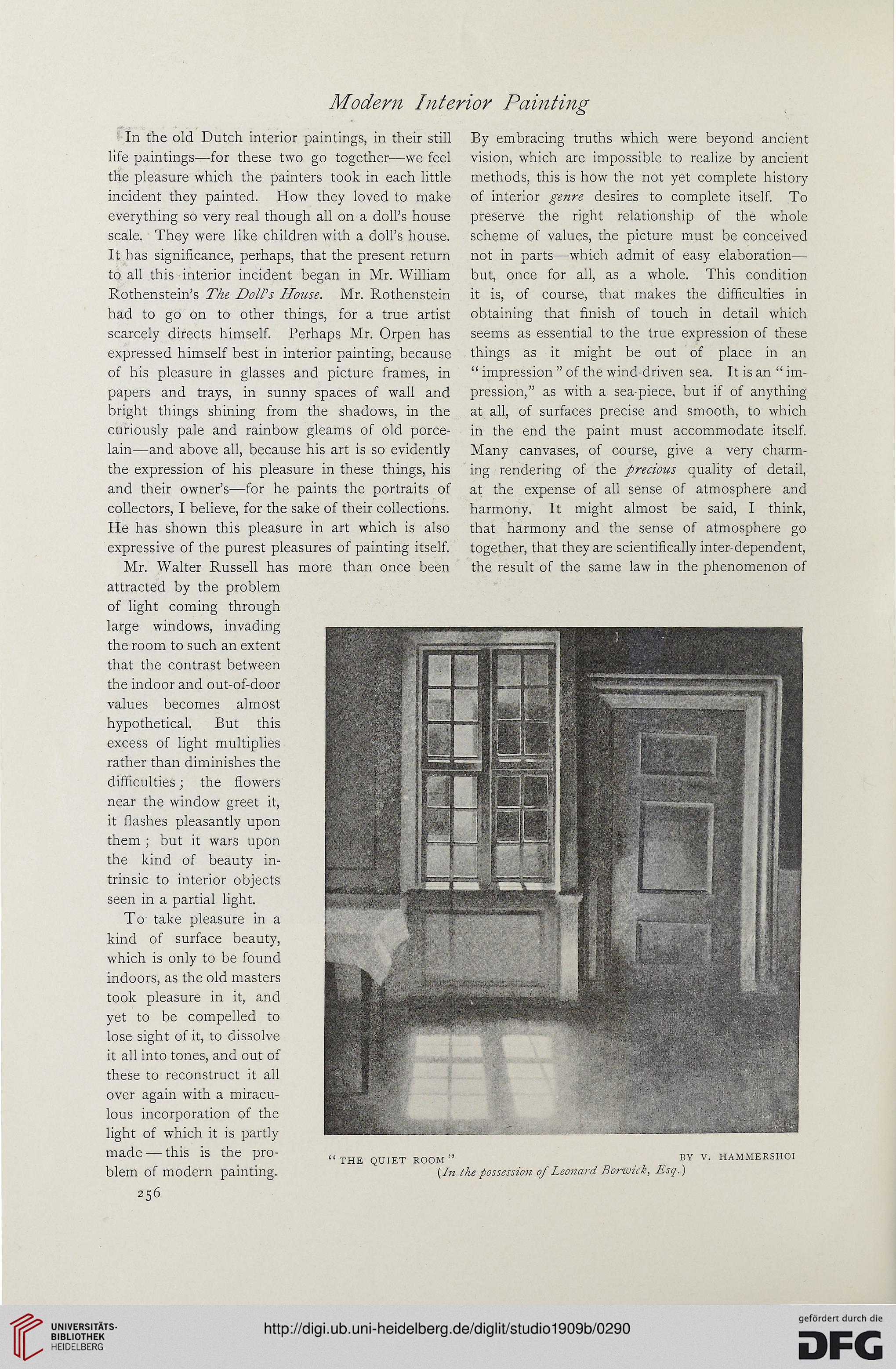

Mr. Walter Russell has more than once been

attracted by the problem

of light coming through

large windows, invading

the room to such an extent

that the contrast between

the indoor and out-of-door

values becomes almost

hypothetical. But this

excess of light multiplies

rather than diminishes the

difficulties; the flowers

near the window greet it,

it flashes pleasantly upon

them ; but it wars upon

the kind of beauty in-

trinsic to interior objects

seen in a partial light.

To take pleasure in a

kind of surface beauty,

which is only to be found

indoors, as the old masters

took pleasure in it, and

yet to be compelled to

lose sight of it, to dissolve

it all into tones, and out of

these to reconstruct it all

over again with a miracu-

lous incorporation of the

light of which it is partly

made — this is the pro-

blem of modern painting.

256

By embracing truths which were beyond ancient

vision, which are impossible to realize by ancient

methods, this is how the not yet complete history

of interior genre desires to complete itself. To

preserve the right relationship of the whole

scheme of values, the picture must be conceived

not in parts—which admit of easy elaboration—

but, once for all, as a whole. This condition

it is, of course, that makes the difficulties in

obtaining that finish of touch in detail which

seems as essential to the true expression of these

things as it might be out of place in an

“ impression ” of the wind-driven sea. It is an “ im-

pression,” as with a sea-piece, but if of anything

at all, of surfaces precise and smooth, to which

in the end the paint must accommodate itself.

Many canvases, of course, give a very charm-

ing rendering of the precious quality of detail,

at the expense of all sense of atmosphere and

harmony. It might almost be said, I think,

that harmony and the sense of atmosphere go

together, that they are scientifically inter-dependent,

the result of the same law in the phenomenon of

In the old Dutch interior paintings, in their still

life paintings—for these two go together—we feel

the pleasure which the painters took in each little

incident they painted. How they loved to make

everything so very real though all on a doll’s house

scale. They were like children with a doll’s house.

It has significance, perhaps, that the present return

to all this interior incident began in Mr. William

Rothenstein’s The Doll's House. Mr. Rothenstein

had to go on to other things, for a true artist

scarcely directs himself. Perhaps Mr. Orpen has

expressed himself best in interior painting, because

of his pleasure in glasses and picture frames, in

papers and trays, in sunny spaces of wall and

bright things shining from the shadows, in the

curiously pale and rainbow gleams of old porce-

lain—and above all, because his art is so evidently

the expression of his pleasure in these things, his

and their owner’s—for he paints the portraits of

collectors, I believe, for the sake of their collections.

He has shown this pleasure in art which is also

expressive of the purest pleasures of painting itself.

Mr. Walter Russell has more than once been

attracted by the problem

of light coming through

large windows, invading

the room to such an extent

that the contrast between

the indoor and out-of-door

values becomes almost

hypothetical. But this

excess of light multiplies

rather than diminishes the

difficulties; the flowers

near the window greet it,

it flashes pleasantly upon

them ; but it wars upon

the kind of beauty in-

trinsic to interior objects

seen in a partial light.

To take pleasure in a

kind of surface beauty,

which is only to be found

indoors, as the old masters

took pleasure in it, and

yet to be compelled to

lose sight of it, to dissolve

it all into tones, and out of

these to reconstruct it all

over again with a miracu-

lous incorporation of the

light of which it is partly

made — this is the pro-

blem of modern painting.

256

By embracing truths which were beyond ancient

vision, which are impossible to realize by ancient

methods, this is how the not yet complete history

of interior genre desires to complete itself. To

preserve the right relationship of the whole

scheme of values, the picture must be conceived

not in parts—which admit of easy elaboration—

but, once for all, as a whole. This condition

it is, of course, that makes the difficulties in

obtaining that finish of touch in detail which

seems as essential to the true expression of these

things as it might be out of place in an

“ impression ” of the wind-driven sea. It is an “ im-

pression,” as with a sea-piece, but if of anything

at all, of surfaces precise and smooth, to which

in the end the paint must accommodate itself.

Many canvases, of course, give a very charm-

ing rendering of the precious quality of detail,

at the expense of all sense of atmosphere and

harmony. It might almost be said, I think,

that harmony and the sense of atmosphere go

together, that they are scientifically inter-dependent,

the result of the same law in the phenomenon of