The Paintings of Leonard Campbell Taylor

An unusual amount of “ high finish ” (for which

dreadful expression, reeking of french-polish, we

apologise) first drew the critics’and thepublic’s atten-

tion to the work of Leonard CampbellTaylor. Pains-

taking finish of such quality one hardly expected

to find in a fin de sidle exhibition. The fact is

Campbell Taylor’s “ finish” is a personal achieve-

ment, worth closer study and analysis ; but before

■we proceed to discuss it from a point of view more

likely to interest the readers of this article (if there

be any such : the writer himself generally prefers to

study the excellent reproductions in The Studio

and to make up his own explanatory text) it is

worth while inquiring why “ highly finished stuff,”

as painters sometimes call such work, generally

appeals to the lay mind much more than “ slick”

painting. Mr. Taylor admits, for instance, that it

is the highly finished work which the

public demand of him. This is

natural: to an eye not trained to

see beyond subject-matter the high

finish of a picture bears all the signs

of patient labour. Time is, as every-

body knows, money; consequently

a work upon which much time has

been spent (thought rarely being a

marketable item) must necessarily,

thinks the man of commerce, be

worth much money. Nevertheless,

the man of commerce is not so

wrong as some would like him to

be. From time immemorial artists

have considered “finishing” the

most difficult part of their trade,

and Manet’s method of visualising

has probably been the cause of

more bad painting than Van

Eyck’s.

The informed eye admires in

Campbell Taylor’s work not so

much the finish as its discreetness.

Where the layman’s mind sees a

polished mahogany table with a

Chinese vase and flowers the ex-

perienced eye distinguishes a con-

cert of colour, admires both melody

and accompaniment, traces with

Appreciation the rise and fall of

light, the little episodes of local

colour, the quiet, unifying passages

of shade, and the symphony of the

tout ensemble. There is no attempt

to deceive the eye. The artist

knows that this means, not a minute

4

representation of isolated facts, but a discreet

selection and arrangement of such facts as the

painter deems both presentable and representable.

In other words, instead of painting all his eyes can

see, he endeavours rather to suppress what he

knows would destroy the unity of his picture. In

his picture Reminiscences he has a convex mirror in

the approved Van Eyck manner with minute

representation of the objects it reflects, and yet

the picture suppresses many facts which the eye of

the artist saw but did not require. In this way

the interest is concentrated on the most important

part of the painting—the heads of the two old

people. All serious modern artists work on these

well-known principles laid down for them by such

great painters as Fantin-Latour, Manet, Chardin,

and Vermeer. The latitude of selection accounts

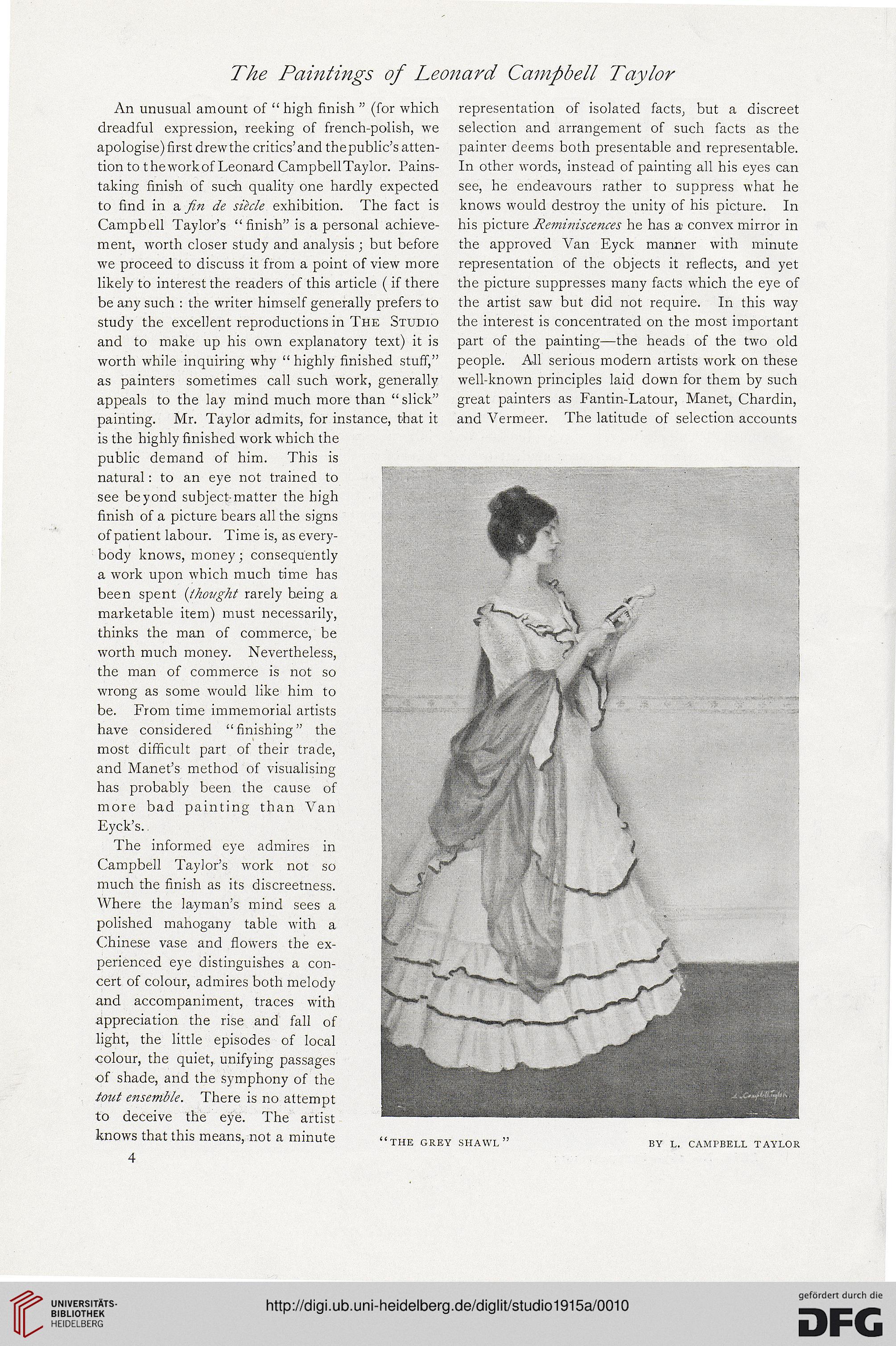

“the grey shawl”

BY L. CAMPBELL TAYLOR

An unusual amount of “ high finish ” (for which

dreadful expression, reeking of french-polish, we

apologise) first drew the critics’and thepublic’s atten-

tion to the work of Leonard CampbellTaylor. Pains-

taking finish of such quality one hardly expected

to find in a fin de sidle exhibition. The fact is

Campbell Taylor’s “ finish” is a personal achieve-

ment, worth closer study and analysis ; but before

■we proceed to discuss it from a point of view more

likely to interest the readers of this article (if there

be any such : the writer himself generally prefers to

study the excellent reproductions in The Studio

and to make up his own explanatory text) it is

worth while inquiring why “ highly finished stuff,”

as painters sometimes call such work, generally

appeals to the lay mind much more than “ slick”

painting. Mr. Taylor admits, for instance, that it

is the highly finished work which the

public demand of him. This is

natural: to an eye not trained to

see beyond subject-matter the high

finish of a picture bears all the signs

of patient labour. Time is, as every-

body knows, money; consequently

a work upon which much time has

been spent (thought rarely being a

marketable item) must necessarily,

thinks the man of commerce, be

worth much money. Nevertheless,

the man of commerce is not so

wrong as some would like him to

be. From time immemorial artists

have considered “finishing” the

most difficult part of their trade,

and Manet’s method of visualising

has probably been the cause of

more bad painting than Van

Eyck’s.

The informed eye admires in

Campbell Taylor’s work not so

much the finish as its discreetness.

Where the layman’s mind sees a

polished mahogany table with a

Chinese vase and flowers the ex-

perienced eye distinguishes a con-

cert of colour, admires both melody

and accompaniment, traces with

Appreciation the rise and fall of

light, the little episodes of local

colour, the quiet, unifying passages

of shade, and the symphony of the

tout ensemble. There is no attempt

to deceive the eye. The artist

knows that this means, not a minute

4

representation of isolated facts, but a discreet

selection and arrangement of such facts as the

painter deems both presentable and representable.

In other words, instead of painting all his eyes can

see, he endeavours rather to suppress what he

knows would destroy the unity of his picture. In

his picture Reminiscences he has a convex mirror in

the approved Van Eyck manner with minute

representation of the objects it reflects, and yet

the picture suppresses many facts which the eye of

the artist saw but did not require. In this way

the interest is concentrated on the most important

part of the painting—the heads of the two old

people. All serious modern artists work on these

well-known principles laid down for them by such

great painters as Fantin-Latour, Manet, Chardin,

and Vermeer. The latitude of selection accounts

“the grey shawl”

BY L. CAMPBELL TAYLOR