The Edmund Davis Collection

an excursion in “ still-life.” Reynolds’s mind was

almost as typically eighteenth century in type as

the writer Gibbon’s. He had the power to sug-

gest, by his handling of the accessories we have

described, the historical perspectives in which his

sitters should be viewed.

Of peculiar beauty are the two Gainsboroughs

in this collection. The charm of a Gainsborough

portrait seems to reside so far within and near the

soul of the sitter that it appears to underlie rather

than to animate gesture and expression. Towards

this order of attainment the art of portraiture has

ever striven ; to this end it has often passed with

a fierce rapidity over the points of costume that

fascinated early painters.

It would seem at times

almost to desire to pass

behind the face itself and

the surface of expression,

to the very “ sea and sky-

line of the soul.”

If the Piano picture in

the Davis Collection seems

to us by far the most im-

portant of the three fine

examples of Whistler’s oil

paintings there — the two

others being the Symphony

in White, No. Ill, and

Old Battersea Bridge—it is

because it foreshadows a

power of emotional re-

sponse which he was to

lose for a time in the

manufacture of effects in

the Japanese manner in

which everything is sacri-

ficed, with a milliner’s zeal,

to “ an arrangement.”

Alfred Stevens, the Bel-

gian petit mailre, of whose

Paintings this collection

contains five examples of

single-figure subjects, was

Particularly susceptible to

the charm of surfaces in

quiet interior lighting. But

the pleasant beauty of his

art is of external character.

He does not divine the soul

°f a room much lived in.

His pictures have not the

power to suggest, as

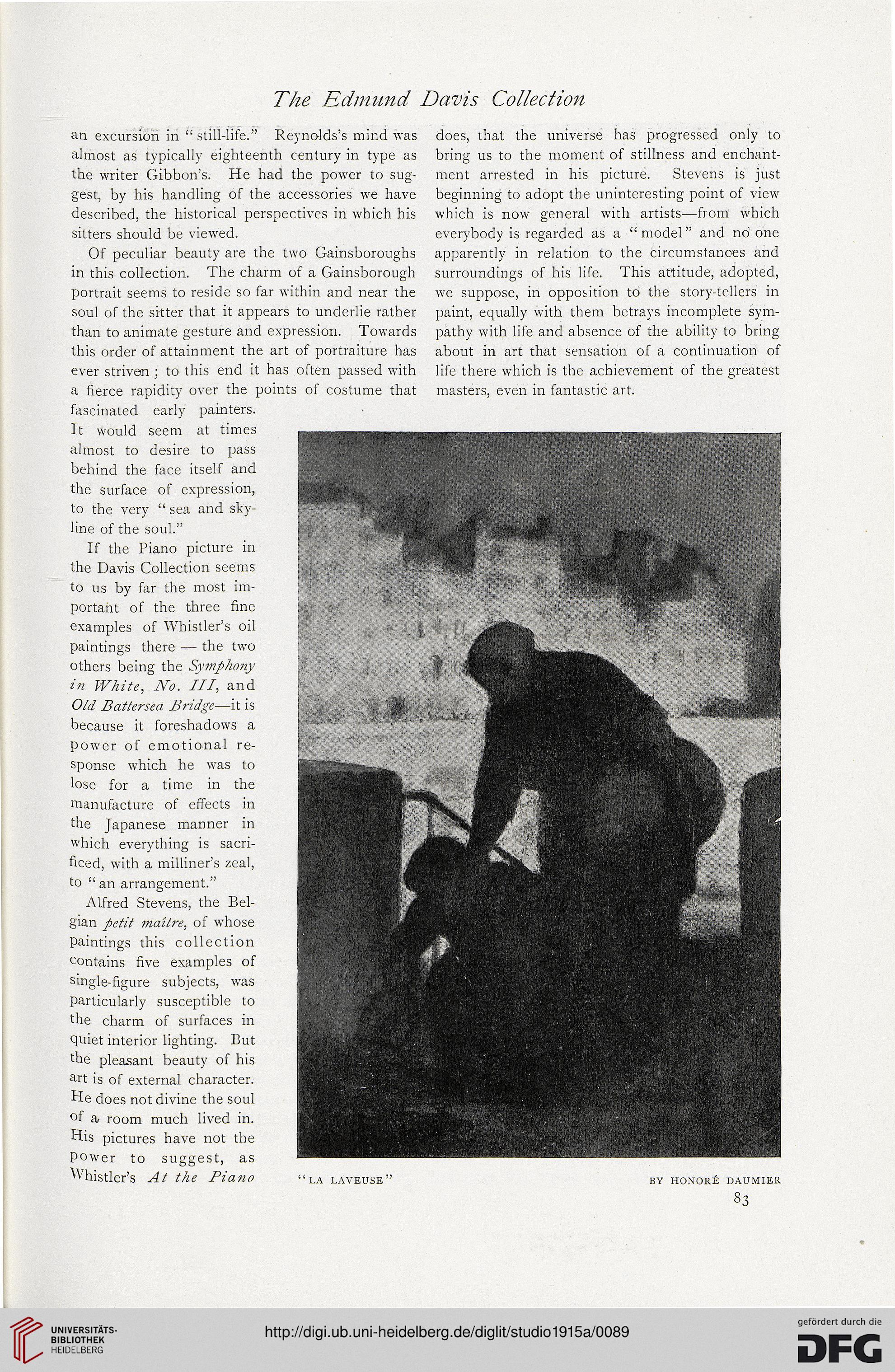

Whistler’s At the Piano “la laveuse”

does, that the universe has progressed only to

bring us to the moment of stillness and enchant-

ment arrested in his picture. Stevens is just

beginning to adopt the uninteresting point of view

which is now general with artists—from w'hich

everybody is regarded as a “model” and no one

apparently in relation to the circumstances and

surroundings of his life. This attitude, adopted,

we suppose, in opposition to the story-tellers in

paint, equally with them betrays incomplete sym-

pathy with life and absence of the ability to bring

about in art that sensation of a continuation of

life there which is the achievement of the greatest

masters, even in fantastic art.

BY HONORS DAUMIER

83

an excursion in “ still-life.” Reynolds’s mind was

almost as typically eighteenth century in type as

the writer Gibbon’s. He had the power to sug-

gest, by his handling of the accessories we have

described, the historical perspectives in which his

sitters should be viewed.

Of peculiar beauty are the two Gainsboroughs

in this collection. The charm of a Gainsborough

portrait seems to reside so far within and near the

soul of the sitter that it appears to underlie rather

than to animate gesture and expression. Towards

this order of attainment the art of portraiture has

ever striven ; to this end it has often passed with

a fierce rapidity over the points of costume that

fascinated early painters.

It would seem at times

almost to desire to pass

behind the face itself and

the surface of expression,

to the very “ sea and sky-

line of the soul.”

If the Piano picture in

the Davis Collection seems

to us by far the most im-

portant of the three fine

examples of Whistler’s oil

paintings there — the two

others being the Symphony

in White, No. Ill, and

Old Battersea Bridge—it is

because it foreshadows a

power of emotional re-

sponse which he was to

lose for a time in the

manufacture of effects in

the Japanese manner in

which everything is sacri-

ficed, with a milliner’s zeal,

to “ an arrangement.”

Alfred Stevens, the Bel-

gian petit mailre, of whose

Paintings this collection

contains five examples of

single-figure subjects, was

Particularly susceptible to

the charm of surfaces in

quiet interior lighting. But

the pleasant beauty of his

art is of external character.

He does not divine the soul

°f a room much lived in.

His pictures have not the

power to suggest, as

Whistler’s At the Piano “la laveuse”

does, that the universe has progressed only to

bring us to the moment of stillness and enchant-

ment arrested in his picture. Stevens is just

beginning to adopt the uninteresting point of view

which is now general with artists—from w'hich

everybody is regarded as a “model” and no one

apparently in relation to the circumstances and

surroundings of his life. This attitude, adopted,

we suppose, in opposition to the story-tellers in

paint, equally with them betrays incomplete sym-

pathy with life and absence of the ability to bring

about in art that sensation of a continuation of

life there which is the achievement of the greatest

masters, even in fantastic art.

BY HONORS DAUMIER

83