The Edmund Davis Collection

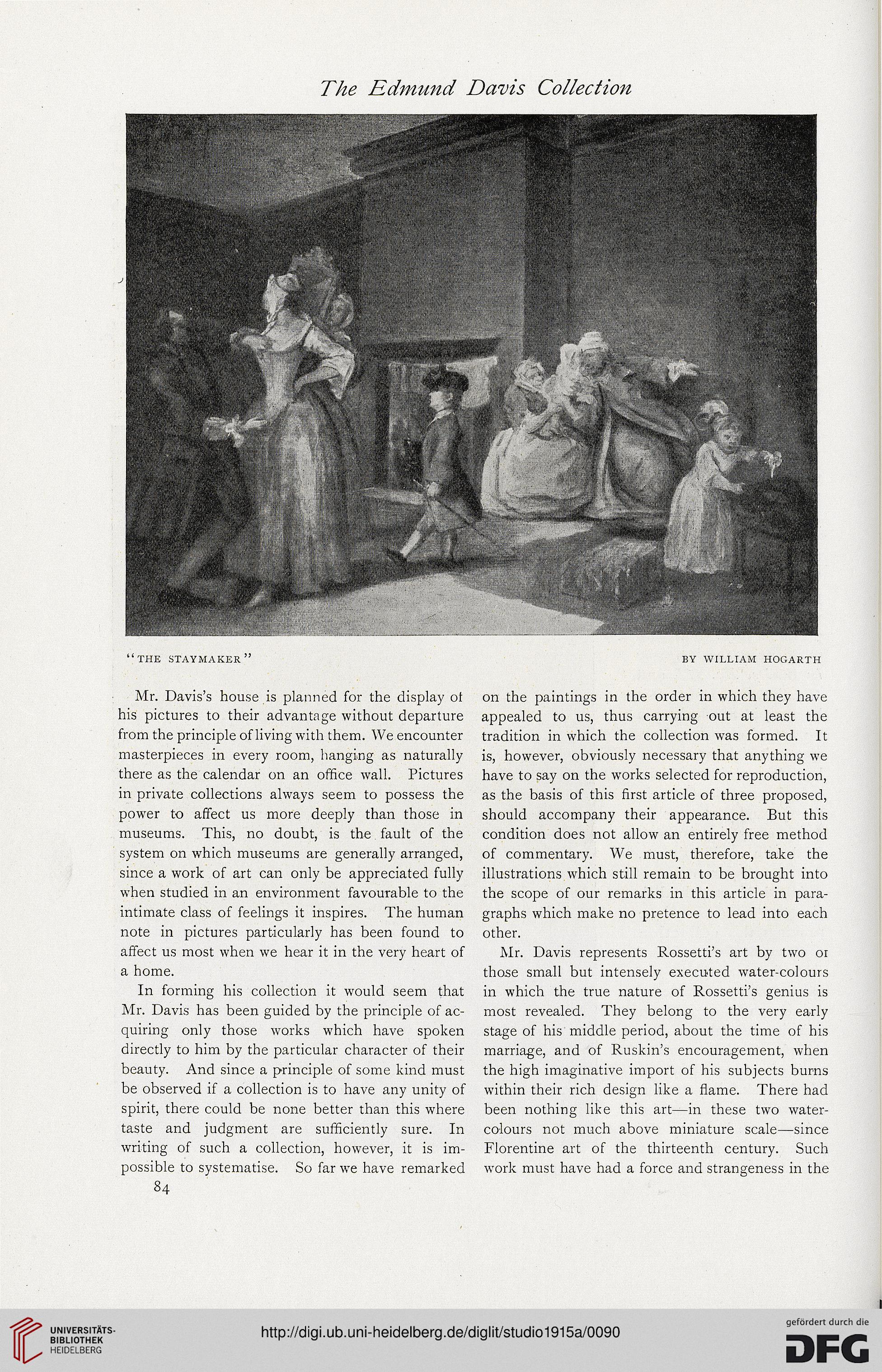

“THE STAYMAKER”

Mr. Davis’s house is planned for the display of

his pictures to their advantage without departure

from the principle of living with them. We encounter

masterpieces in every room, hanging as naturally

there as the calendar on an office wall. Pictures

in private collections always seem to possess the

power to affect us more deeply than those in

museums. This, no doubt, is the fault of the

system on which museums are generally arranged,

since a work of art can only be appreciated fully

when studied in an environment favourable to the

intimate class of feelings it inspires. The human

note in pictures particularly has been found to

affect us most when we hear it in the very heart of

a home.

In forming his collection it would seem that

Mr. Davis has been guided by the principle of ac-

quiring only those works which have spoken

directly to him by the particular character of their

beauty. And since a principle of some kind must

be observed if a collection is to have any unity of

spirit, there could be none better than this where

taste and judgment are sufficiently sure. In

writing of such a collection, however, it is im-

possible to systematise. So far we have remarked

84

BY WILLIAM HOGARTH

on the paintings in the order in which they have

appealed to us, thus carrying out at least the

tradition in which the collection was formed. It

is, however, obviously necessary that anything we

have to say on the works selected for reproduction,

as the basis of this first article of three proposed,

should accompany their appearance. But this

condition does not allow an entirely free method

of commentary. We must, therefore, take the

illustrations which still remain to be brought into

the scope of our remarks in this article in para-

graphs which make no pretence to lead into each

other.

Mr. Davis represents Rossetti’s art by two 01

those small but intensely executed water-colours

in which the true nature of Rossetti’s genius is

most revealed. They belong to the very early

stage of his middle period, about the time of his

marriage, and of Ruskin’s encouragement, when

the high imaginative import of his subjects burns

within their rich design like a flame. There had

been nothing like this art—in these two water-

colours not much above miniature scale—since

Florentine art of the thirteenth century. Such

work must have had a force and strangeness in the

“THE STAYMAKER”

Mr. Davis’s house is planned for the display of

his pictures to their advantage without departure

from the principle of living with them. We encounter

masterpieces in every room, hanging as naturally

there as the calendar on an office wall. Pictures

in private collections always seem to possess the

power to affect us more deeply than those in

museums. This, no doubt, is the fault of the

system on which museums are generally arranged,

since a work of art can only be appreciated fully

when studied in an environment favourable to the

intimate class of feelings it inspires. The human

note in pictures particularly has been found to

affect us most when we hear it in the very heart of

a home.

In forming his collection it would seem that

Mr. Davis has been guided by the principle of ac-

quiring only those works which have spoken

directly to him by the particular character of their

beauty. And since a principle of some kind must

be observed if a collection is to have any unity of

spirit, there could be none better than this where

taste and judgment are sufficiently sure. In

writing of such a collection, however, it is im-

possible to systematise. So far we have remarked

84

BY WILLIAM HOGARTH

on the paintings in the order in which they have

appealed to us, thus carrying out at least the

tradition in which the collection was formed. It

is, however, obviously necessary that anything we

have to say on the works selected for reproduction,

as the basis of this first article of three proposed,

should accompany their appearance. But this

condition does not allow an entirely free method

of commentary. We must, therefore, take the

illustrations which still remain to be brought into

the scope of our remarks in this article in para-

graphs which make no pretence to lead into each

other.

Mr. Davis represents Rossetti’s art by two 01

those small but intensely executed water-colours

in which the true nature of Rossetti’s genius is

most revealed. They belong to the very early

stage of his middle period, about the time of his

marriage, and of Ruskin’s encouragement, when

the high imaginative import of his subjects burns

within their rich design like a flame. There had

been nothing like this art—in these two water-

colours not much above miniature scale—since

Florentine art of the thirteenth century. Such

work must have had a force and strangeness in the