The Edmund Davis Collection—II

It is seldom enough that a modern picture secures

this transcendental result, but in that direction lies

the secret of the enchantment of costume as de-

picted in ancient art.

From the point of view of strict criticism of

painting it may seem, at first, somewhat absurd to

suggest that just a little additional glamour, valuable

to the picture itself, may lie with the difference

between the use of the fanciful title Les Mar?tiitons

and its plebeian translation. The more fanciful

sounding French is in agreement with the qualities

of the picture, for there is relationship between the

imagery that words evoke and forms made tangible

in painting. Indeed a poem and a picture may be

related in a sense in which two paintings are not,

and to overlook relationships of this abstract kind

between the arts is to lose the key to everything

temperamental; in criticism it is to knock at closed

doors, and come away only with a'report on the

varnish.

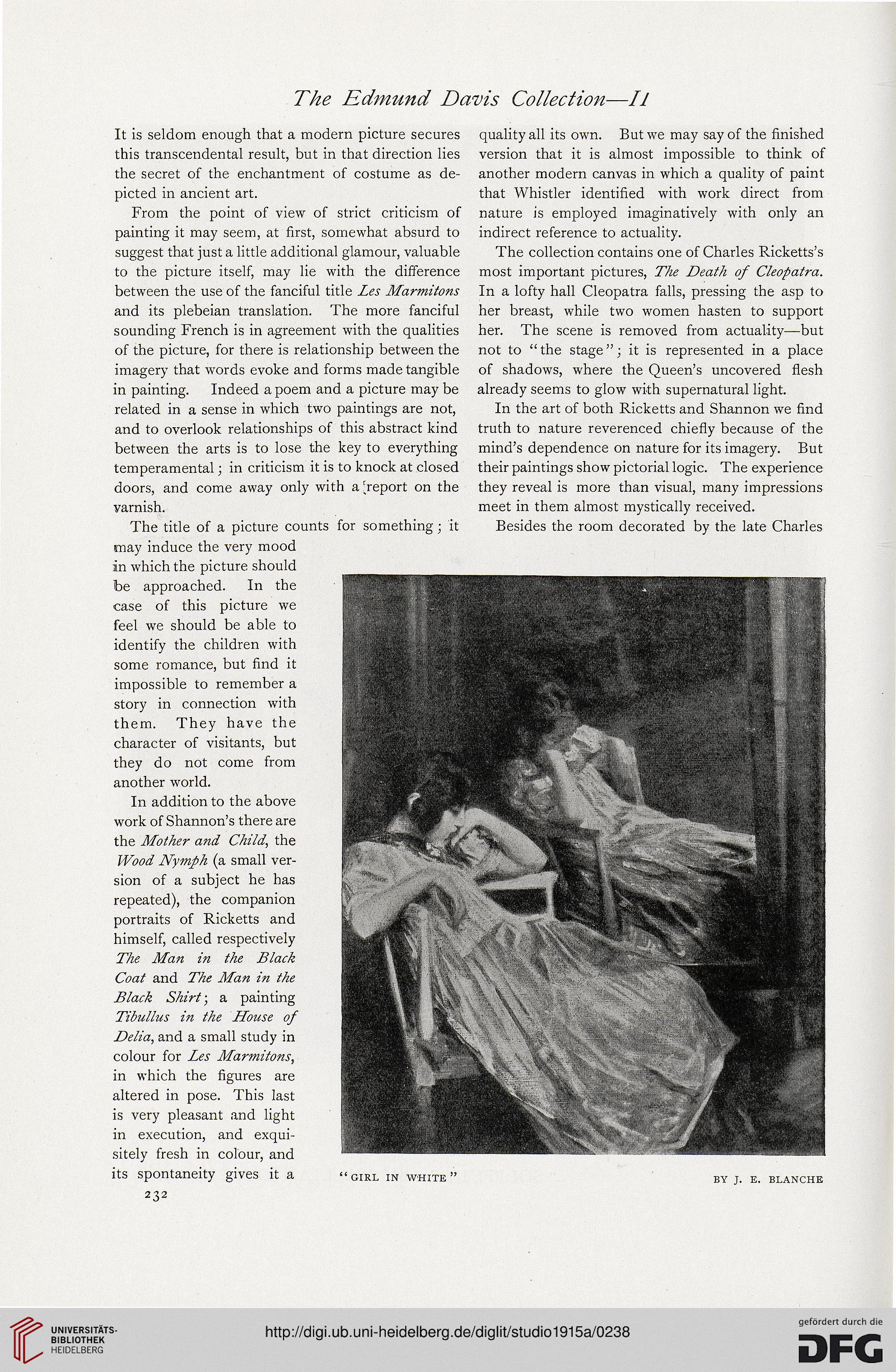

The title of a picture counts for something; it

may induce the very mood

in which the picture should

be approached. In the

case of this picture we

feel we should be able to

identify the children with

some romance, but find it

impossible to remember a

story in connection with

them. They have the

character of visitants, but

they do not come from

another world.

In addition to the above

work of Shannon’s there are

the Mother and Child, the

Wood Nymph (a small ver-

sion of a subject he has

repeated), the companion

portraits of Ricketts and

himself, called respectively

The Man in the Black

Coat and The Man in the

Black Shirt; a painting

Tibullus in the House of

Delia, and a small study in

colour for Les Marmitons,

in which the figures are

altered in pose. This last

is very pleasant and light

in execution, and exqui-

sitely fresh in colour, and

its spontaneity gives it a “girl in white”

232

quality all its own. But we may say of the finished

version that it is almost impossible to think of

another modem canvas in which a quality of paint

that Whistler identified with work direct from

nature is employed imaginatively with only an

indirect reference to actuality.

The collection contains one of Charles Ricketts’s

most important pictures, The Death of Cleopatra.

In a lofty hall Cleopatra falls, pressing the asp to

her breast, while two women hasten to support

her. The scene is removed from actuality—but

not to “ the stage ”; it is represented in a place

of shadows, where the Queen’s uncovered flesh

already seems to glow with supernatural light.

In the art of both Ricketts and Shannon we find

truth to nature reverenced chiefly because of the

mind’s dependence on nature for its imagery. But

their paintings show pictorial logic. The experience

they reveal is more than visual, many impressions

meet in them almost mystically received.

Besides the room decorated by the late Charles

BY J. E. BLANCHE

It is seldom enough that a modern picture secures

this transcendental result, but in that direction lies

the secret of the enchantment of costume as de-

picted in ancient art.

From the point of view of strict criticism of

painting it may seem, at first, somewhat absurd to

suggest that just a little additional glamour, valuable

to the picture itself, may lie with the difference

between the use of the fanciful title Les Mar?tiitons

and its plebeian translation. The more fanciful

sounding French is in agreement with the qualities

of the picture, for there is relationship between the

imagery that words evoke and forms made tangible

in painting. Indeed a poem and a picture may be

related in a sense in which two paintings are not,

and to overlook relationships of this abstract kind

between the arts is to lose the key to everything

temperamental; in criticism it is to knock at closed

doors, and come away only with a'report on the

varnish.

The title of a picture counts for something; it

may induce the very mood

in which the picture should

be approached. In the

case of this picture we

feel we should be able to

identify the children with

some romance, but find it

impossible to remember a

story in connection with

them. They have the

character of visitants, but

they do not come from

another world.

In addition to the above

work of Shannon’s there are

the Mother and Child, the

Wood Nymph (a small ver-

sion of a subject he has

repeated), the companion

portraits of Ricketts and

himself, called respectively

The Man in the Black

Coat and The Man in the

Black Shirt; a painting

Tibullus in the House of

Delia, and a small study in

colour for Les Marmitons,

in which the figures are

altered in pose. This last

is very pleasant and light

in execution, and exqui-

sitely fresh in colour, and

its spontaneity gives it a “girl in white”

232

quality all its own. But we may say of the finished

version that it is almost impossible to think of

another modem canvas in which a quality of paint

that Whistler identified with work direct from

nature is employed imaginatively with only an

indirect reference to actuality.

The collection contains one of Charles Ricketts’s

most important pictures, The Death of Cleopatra.

In a lofty hall Cleopatra falls, pressing the asp to

her breast, while two women hasten to support

her. The scene is removed from actuality—but

not to “ the stage ”; it is represented in a place

of shadows, where the Queen’s uncovered flesh

already seems to glow with supernatural light.

In the art of both Ricketts and Shannon we find

truth to nature reverenced chiefly because of the

mind’s dependence on nature for its imagery. But

their paintings show pictorial logic. The experience

they reveal is more than visual, many impressions

meet in them almost mystically received.

Besides the room decorated by the late Charles

BY J. E. BLANCHE