The Art of Joseph Craw hall

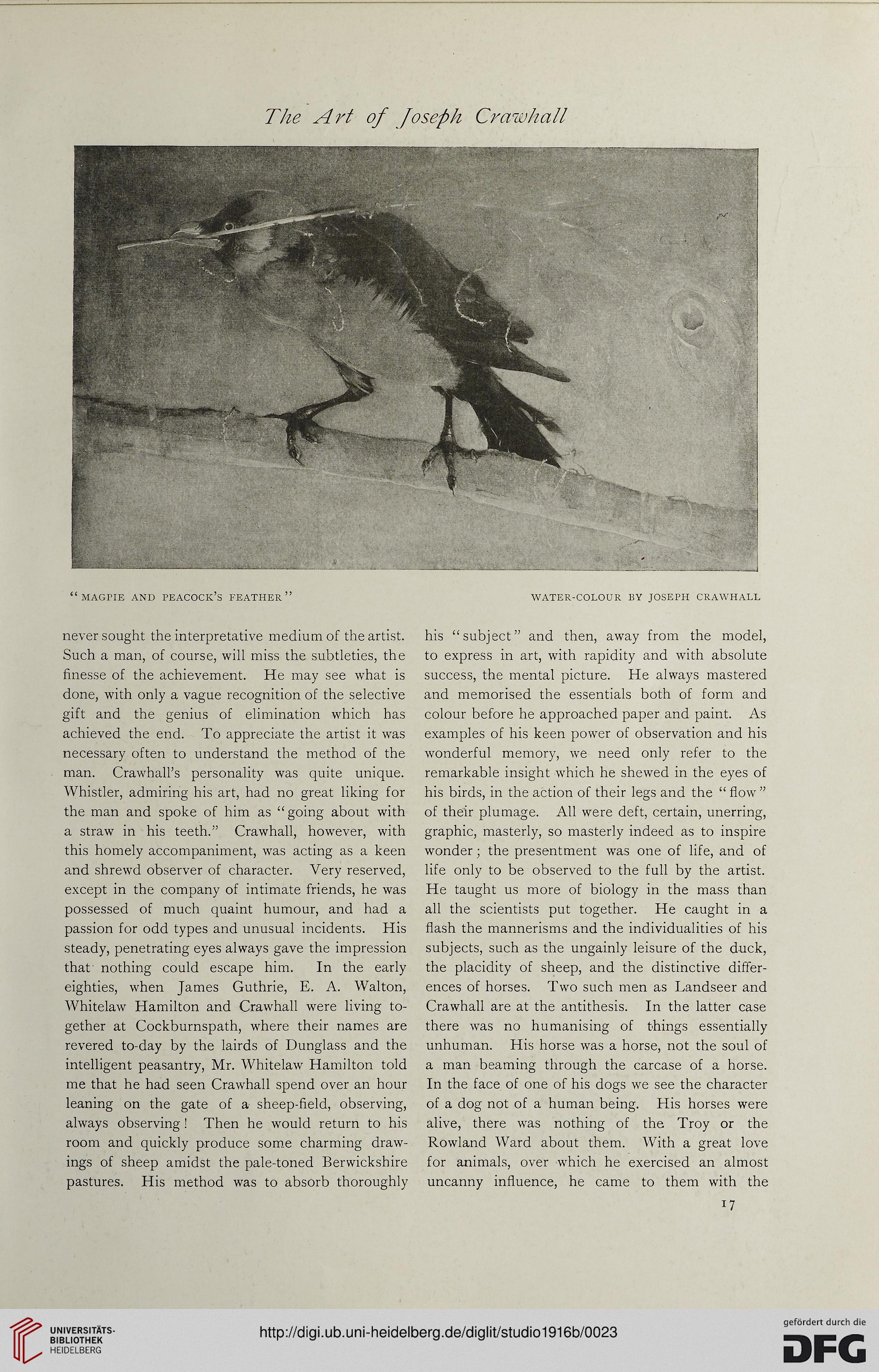

" MAGPIE AND PEACOCK'S FEATHER "

never sought the interpretative medium of the artist.

Such a man, of course, will miss the subtleties, the

finesse of the achievement. He may see what is

done, with only a vague recognition of the selective

gift and the genius of elimination which has

achieved the end. To appreciate the artist it was

necessary often to understand the method of the

man. Crawhall's personality was quite unique.

Whistler, admiring his art, had no great liking for

the man and spoke of him as "going about with

a straw in his teeth." Crawhall, however, with

this homely accompaniment, was acting as a keen

and shrewd observer of character. Very reserved,

except in the company of intimate friends, he was

possessed of much quaint humour, and had a

passion for odd types and unusual incidents. His

steady, penetrating eyes always gave the impression

that nothing could escape him. In the early

eighties, when James Guthrie, E. A. Walton,

Whitelaw Hamilton and Crawhall were living to-

gether at Cockburnspath, where their names are

revered to-day by the lairds of Dunglass and the

intelligent peasantry, Mr. Whitelaw Hamilton told

me that he had seen Crawhall spend over an hour

leaning on the gate of a sheep-field, observing,

always observing! Then he would return to his

room and quickly produce some charming draw-

ings of sheep amidst the pale-toned Berwickshire

pastures. His method was to absorb thoroughly

WATER-COLOUR BY JOSEPH CRAWHALL

his "subject" and then, away from the model,

to express in art, with rapidity and with absolute

success, the mental picture. He always mastered

and memorised the essentials both of form and

colour before he approached paper and paint. As

examples of his keen power of observation and his

wonderful memory, we need only refer to the

remarkable insight which he shewed in the eyes of

his birds, in the action of their legs and the " flow "

of their plumage. All were deft, certain, unerring,

graphic, masterly, so masterly indeed as to inspire

wonder; the presentment was one of life, and of

life only to be observed to the full by the artist.

He taught us more of biology in the mass than

all the scientists put together. He caught in a

flash the mannerisms and the individualities of his

subjects, such as the ungainly leisure of the duck,

the placidity of sheep, and the distinctive differ-

ences of horses. Two such men as Landseer and

Crawhall are at the antithesis. In the latter case

there was no humanising of things essentially

unhuman. His horse was a horse, not the soul of

a man beaming through the carcase of a horse.

In the face of one of his dogs we see the character

of a dog not of a human being. His horses were

alive, there was nothing of the Troy or the

Rowland Ward about them. With a great love

for animals, over which he exercised an almost

uncanny influence, he came to them with the

17

" MAGPIE AND PEACOCK'S FEATHER "

never sought the interpretative medium of the artist.

Such a man, of course, will miss the subtleties, the

finesse of the achievement. He may see what is

done, with only a vague recognition of the selective

gift and the genius of elimination which has

achieved the end. To appreciate the artist it was

necessary often to understand the method of the

man. Crawhall's personality was quite unique.

Whistler, admiring his art, had no great liking for

the man and spoke of him as "going about with

a straw in his teeth." Crawhall, however, with

this homely accompaniment, was acting as a keen

and shrewd observer of character. Very reserved,

except in the company of intimate friends, he was

possessed of much quaint humour, and had a

passion for odd types and unusual incidents. His

steady, penetrating eyes always gave the impression

that nothing could escape him. In the early

eighties, when James Guthrie, E. A. Walton,

Whitelaw Hamilton and Crawhall were living to-

gether at Cockburnspath, where their names are

revered to-day by the lairds of Dunglass and the

intelligent peasantry, Mr. Whitelaw Hamilton told

me that he had seen Crawhall spend over an hour

leaning on the gate of a sheep-field, observing,

always observing! Then he would return to his

room and quickly produce some charming draw-

ings of sheep amidst the pale-toned Berwickshire

pastures. His method was to absorb thoroughly

WATER-COLOUR BY JOSEPH CRAWHALL

his "subject" and then, away from the model,

to express in art, with rapidity and with absolute

success, the mental picture. He always mastered

and memorised the essentials both of form and

colour before he approached paper and paint. As

examples of his keen power of observation and his

wonderful memory, we need only refer to the

remarkable insight which he shewed in the eyes of

his birds, in the action of their legs and the " flow "

of their plumage. All were deft, certain, unerring,

graphic, masterly, so masterly indeed as to inspire

wonder; the presentment was one of life, and of

life only to be observed to the full by the artist.

He taught us more of biology in the mass than

all the scientists put together. He caught in a

flash the mannerisms and the individualities of his

subjects, such as the ungainly leisure of the duck,

the placidity of sheep, and the distinctive differ-

ences of horses. Two such men as Landseer and

Crawhall are at the antithesis. In the latter case

there was no humanising of things essentially

unhuman. His horse was a horse, not the soul of

a man beaming through the carcase of a horse.

In the face of one of his dogs we see the character

of a dog not of a human being. His horses were

alive, there was nothing of the Troy or the

Rowland Ward about them. With a great love

for animals, over which he exercised an almost

uncanny influence, he came to them with the

17