Ksedjbeh

157

northern hills. The great majority of buildings, particularly of buildings that are well

preserved, were constructed of finely dressed quadrated blocks of limestone in courses

varying from 50 to 70 cm. wide and 55 cm. thick. The joints were close and true,

and the walls were but one stone in thickness. In walls of this kind the jambs of

doorways are sometimes monoliths inserted in the coursing, but, more often, the jambs

are cut on the ends of the courses. In a number of cases, in examples of what might

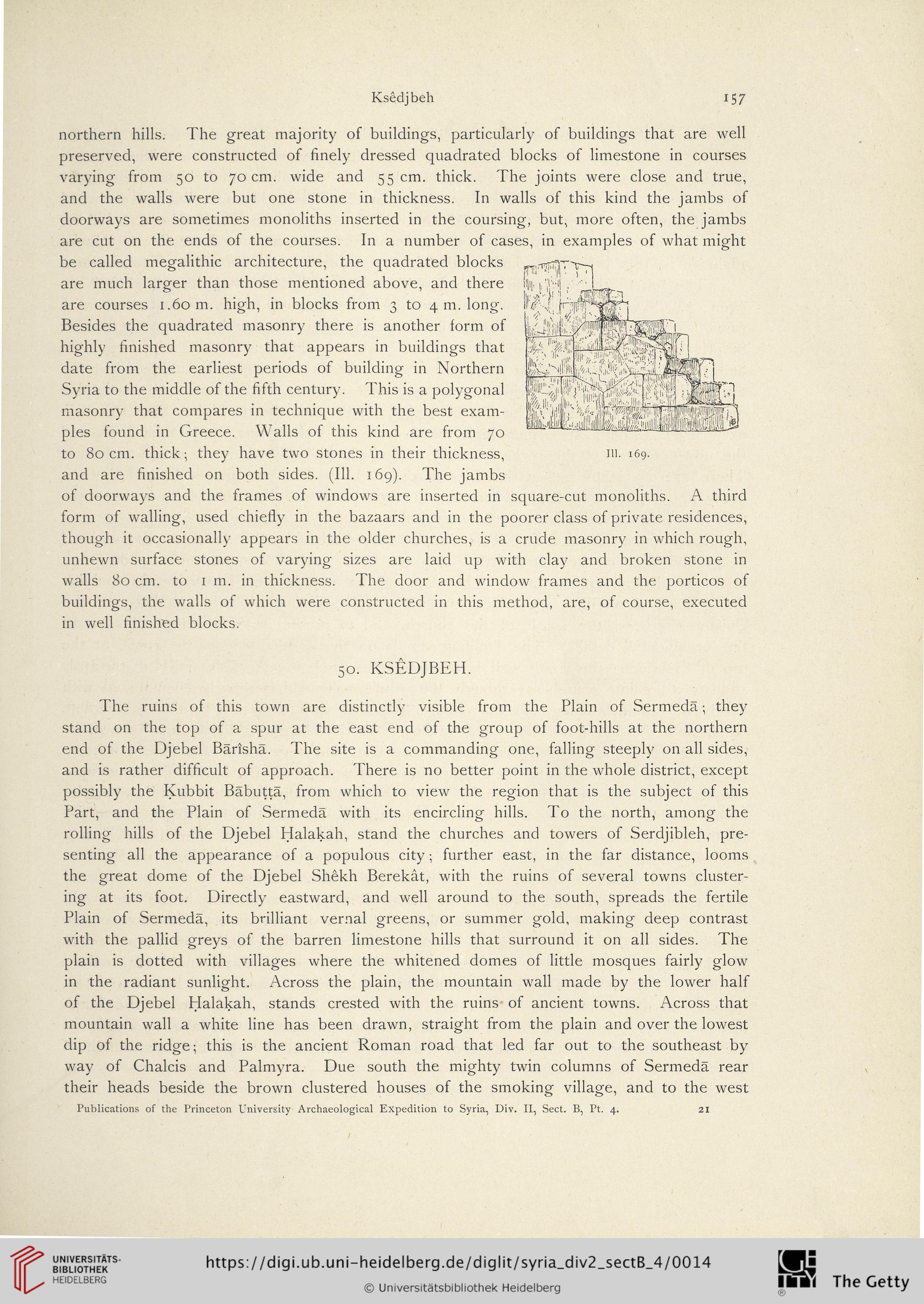

be called megalithic architecture, the quadrated blocks

are much larger than those mentioned above, and there

are courses 1.60 m. high, in blocks from 3 to 4 m. long.

Besides the quadrated masonry there is another form of

highly finished masonry that appears in buildings that

date from the earliest periods of building in Northern

Syria to the middle of the fifth century. This is a polygonal

masonry that compares in technique with the best exam¬

ples found in Greece. Walls of this kind are from 70

to 80 cm. thick; they have two stones in their thickness, m. 169.

and are finished on both sides. (Ill. 169). The jambs

of doorways and the frames of windows are inserted in square-cut monoliths. A third

form of walling, used chiefly in the bazaars and in the poorer class of private residences,

though it occasionally appears in the older churches, is a crude masonry in which rough,

unhewn surface stones of varying sizes are laid up with clay and broken stone in

walls 80 cm. to 1 m. in thickness. The door and window frames and the porticos of

buildings, the walls of which were constructed in this method, are, of course, executed

in well finished blocks.

50. KSEDJBEH.

The ruins of this town are distinctly visible from the Plain of Sermeda; they

stand on the top of a spur at the east end of the group of foot-hills at the northern

end of the Djebel Barisha. The site is a commanding one, falling steeply on all sides,

and is rather difficult of approach. There is no better point in the whole district, except

possibly the Kubbit Babutta, from which to view the region that is the subject of this

Part, and the Plain of Sermeda with its encircling hills. To the north, among the

rolling hills of the Djebel Halakah, stand the churches and towers of Serdjibleh, pre-

senting all the appearance of a populous city; further east, in the far distance, looms

the great dome of the Djebel Shekh Berekat, with the ruins of several towns cluster-

ing at its foot. Directly eastward, and well around to the south, spreads the fertile

Plain of Sermeda, its brilliant vernal greens, or summer gold, making deep contrast

with the pallid greys of the barren limestone hills that surround it on all sides. The

plain is dotted with villages where the whitened domes of little mosques fairly glow

in the radiant sunlight. Across the plain, the mountain wall made by the lower half

of the Djebel Halakah, stands crested with the ruins of ancient towns. Across that

mountain wall a white line has been drawn, straight from the plain and over the lowest

dip of the ridge; this is the ancient Roman road that led far out to the southeast by

way of Chaicis and Palmyra. Due south the mighty twin columns of Sermeda rear

their heads beside the brown clustered houses of the smoking village, and to the west

Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria, Div. II, Sect. B, Pt. 4. 21

157

northern hills. The great majority of buildings, particularly of buildings that are well

preserved, were constructed of finely dressed quadrated blocks of limestone in courses

varying from 50 to 70 cm. wide and 55 cm. thick. The joints were close and true,

and the walls were but one stone in thickness. In walls of this kind the jambs of

doorways are sometimes monoliths inserted in the coursing, but, more often, the jambs

are cut on the ends of the courses. In a number of cases, in examples of what might

be called megalithic architecture, the quadrated blocks

are much larger than those mentioned above, and there

are courses 1.60 m. high, in blocks from 3 to 4 m. long.

Besides the quadrated masonry there is another form of

highly finished masonry that appears in buildings that

date from the earliest periods of building in Northern

Syria to the middle of the fifth century. This is a polygonal

masonry that compares in technique with the best exam¬

ples found in Greece. Walls of this kind are from 70

to 80 cm. thick; they have two stones in their thickness, m. 169.

and are finished on both sides. (Ill. 169). The jambs

of doorways and the frames of windows are inserted in square-cut monoliths. A third

form of walling, used chiefly in the bazaars and in the poorer class of private residences,

though it occasionally appears in the older churches, is a crude masonry in which rough,

unhewn surface stones of varying sizes are laid up with clay and broken stone in

walls 80 cm. to 1 m. in thickness. The door and window frames and the porticos of

buildings, the walls of which were constructed in this method, are, of course, executed

in well finished blocks.

50. KSEDJBEH.

The ruins of this town are distinctly visible from the Plain of Sermeda; they

stand on the top of a spur at the east end of the group of foot-hills at the northern

end of the Djebel Barisha. The site is a commanding one, falling steeply on all sides,

and is rather difficult of approach. There is no better point in the whole district, except

possibly the Kubbit Babutta, from which to view the region that is the subject of this

Part, and the Plain of Sermeda with its encircling hills. To the north, among the

rolling hills of the Djebel Halakah, stand the churches and towers of Serdjibleh, pre-

senting all the appearance of a populous city; further east, in the far distance, looms

the great dome of the Djebel Shekh Berekat, with the ruins of several towns cluster-

ing at its foot. Directly eastward, and well around to the south, spreads the fertile

Plain of Sermeda, its brilliant vernal greens, or summer gold, making deep contrast

with the pallid greys of the barren limestone hills that surround it on all sides. The

plain is dotted with villages where the whitened domes of little mosques fairly glow

in the radiant sunlight. Across the plain, the mountain wall made by the lower half

of the Djebel Halakah, stands crested with the ruins of ancient towns. Across that

mountain wall a white line has been drawn, straight from the plain and over the lowest

dip of the ridge; this is the ancient Roman road that led far out to the southeast by

way of Chaicis and Palmyra. Due south the mighty twin columns of Sermeda rear

their heads beside the brown clustered houses of the smoking village, and to the west

Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria, Div. II, Sect. B, Pt. 4. 21