163

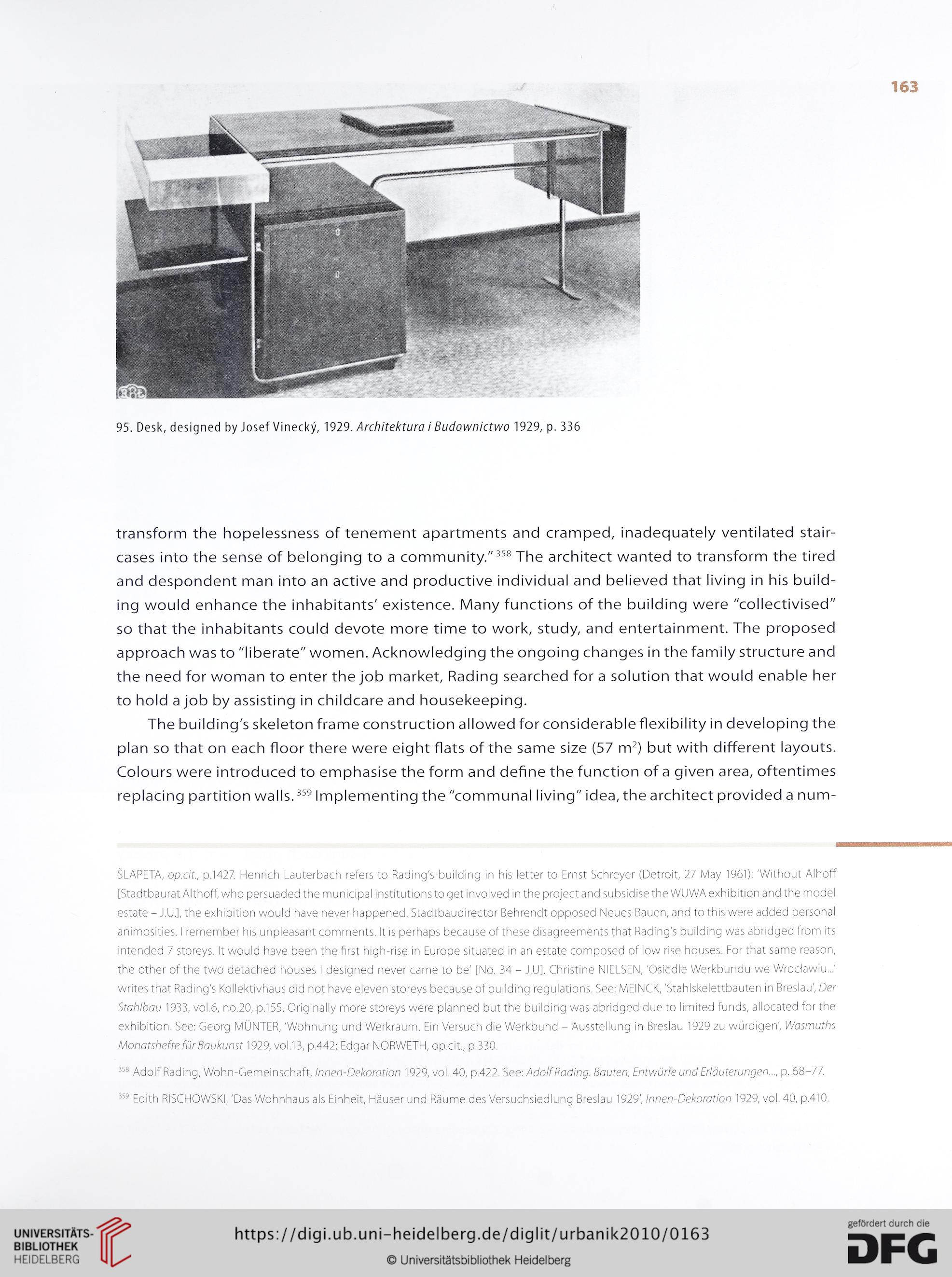

95. Desk, designed by Josef Vinecky, 1929. Architektura i Budownictwo 1929, p. 336

transform the hopelessness of tenement apartments and cramped, inadequately ventilated stair-

cases into the sense of belonging to a community."358 The architect wanted to transform the tired

and despondent man into an active and productive individual and believed that living in his build-

ing would enhance the inhabitants' existence. Many functions of the building were "collectivised"

so that the inhabitants could devote more time to work, study, and entertainment. The proposed

approach was to "liberate" women. Acknowledging the ongoing changes in the family structure and

the need for woman to enter the job market, Rading searched for a solution that would enable her

to hold a job by assisting in childcare and housekeeping.

The building's skeleton frame construction allowed for considerable flexibility in developing the

plan so that on each floor there were eight flats of the same size (57 m2) but with different layouts.

Colours were introduced to emphasise the form and define the function of a given area, oftentimes

replacing partition walls.359 Implementing the "communal living" idea, the architect provided a num-

SLAPETA, op.cit., p.1427. Henrich Lauterbach refers to Rading's building in his letter to Ernst Schreyer (Detroit, 27 May 1961): 'Without Alhoff

[Stadtbaurat Althoff, who persuaded the municipal institutions to get involved in the project and subsidise the WUWA exhibition and the mode

estate - J.U.], the exhibition would have never happened. Stadtbaudirector Behrendt opposed Neues Bauen, and to this were added personal

animosities. I remember his unpleasant comments. It is perhaps because of these disagreements that Rading's building was abridged from its

intended 7 storeys. It would have been the first high-rise in Europe situated in an estate composed of low rise houses. For that same reason,

the other of the two detached houses I designed never came to be' [No. 34 - J.U], Christine NIELSEN, 'Osiedle Werkbundu we Wrodawiu...'

writes that Rading's Kollektivhaus did not have eleven storeys because of building regulations. See: MEINCK, 'Stahlskelettbauten in Breslau', Der

Stahlbau 1933, vol.6, no.20, p.155. Originally more storeys were planned but the building was abridged due to limited funds, allocated for the

exhibition. See: Georg MUNTER, 'Wohnung und Werkraum. Ein Versuch die Werkbund - Ausstellung in Breslau 1929 zu wurdigen', Wasmuths

Monatshefte furBaukunst 1929, vol.13, p.442; Edgar NORWETH, op.cit., p.33O.

358 Adolf Rading, Wohn-Gemeinschaft, Innen-Dekoration 1929, vol. 40, p.422. See: Adolf Rading. Bauten, Entwurfe und Erlauterungen..., p. 68-77.

359 Edith RISCHOWSKI, 'Das Wohnhaus als Einheit, Hauser und Raume des Versuchsiedlung Breslau 1929', Innen-Dekoration 1929, vol. 40, p.4'10.

95. Desk, designed by Josef Vinecky, 1929. Architektura i Budownictwo 1929, p. 336

transform the hopelessness of tenement apartments and cramped, inadequately ventilated stair-

cases into the sense of belonging to a community."358 The architect wanted to transform the tired

and despondent man into an active and productive individual and believed that living in his build-

ing would enhance the inhabitants' existence. Many functions of the building were "collectivised"

so that the inhabitants could devote more time to work, study, and entertainment. The proposed

approach was to "liberate" women. Acknowledging the ongoing changes in the family structure and

the need for woman to enter the job market, Rading searched for a solution that would enable her

to hold a job by assisting in childcare and housekeeping.

The building's skeleton frame construction allowed for considerable flexibility in developing the

plan so that on each floor there were eight flats of the same size (57 m2) but with different layouts.

Colours were introduced to emphasise the form and define the function of a given area, oftentimes

replacing partition walls.359 Implementing the "communal living" idea, the architect provided a num-

SLAPETA, op.cit., p.1427. Henrich Lauterbach refers to Rading's building in his letter to Ernst Schreyer (Detroit, 27 May 1961): 'Without Alhoff

[Stadtbaurat Althoff, who persuaded the municipal institutions to get involved in the project and subsidise the WUWA exhibition and the mode

estate - J.U.], the exhibition would have never happened. Stadtbaudirector Behrendt opposed Neues Bauen, and to this were added personal

animosities. I remember his unpleasant comments. It is perhaps because of these disagreements that Rading's building was abridged from its

intended 7 storeys. It would have been the first high-rise in Europe situated in an estate composed of low rise houses. For that same reason,

the other of the two detached houses I designed never came to be' [No. 34 - J.U], Christine NIELSEN, 'Osiedle Werkbundu we Wrodawiu...'

writes that Rading's Kollektivhaus did not have eleven storeys because of building regulations. See: MEINCK, 'Stahlskelettbauten in Breslau', Der

Stahlbau 1933, vol.6, no.20, p.155. Originally more storeys were planned but the building was abridged due to limited funds, allocated for the

exhibition. See: Georg MUNTER, 'Wohnung und Werkraum. Ein Versuch die Werkbund - Ausstellung in Breslau 1929 zu wurdigen', Wasmuths

Monatshefte furBaukunst 1929, vol.13, p.442; Edgar NORWETH, op.cit., p.33O.

358 Adolf Rading, Wohn-Gemeinschaft, Innen-Dekoration 1929, vol. 40, p.422. See: Adolf Rading. Bauten, Entwurfe und Erlauterungen..., p. 68-77.

359 Edith RISCHOWSKI, 'Das Wohnhaus als Einheit, Hauser und Raume des Versuchsiedlung Breslau 1929', Innen-Dekoration 1929, vol. 40, p.4'10.