90

HANDBOOK OF ABCEJEOLOGT.

of those stupendous structures are to be met with not only in the

neighbourhood of Rome, but also throughout the Roman provinces

in Europe, Asia, and Africa. They were apparent or subterranean.

The latter, which sometimes traversed considerable space, and were

carried through rocks, contained pipes (fistula;, tubuli) of lead or

terra cotta, frequently marked either with the name of the potter, or

the name of the consuls in whose time they were laid down. At con-

venient points, in the course of these aqueducts, as it was necessary

from the water being conveyed through pipes, there were reservoirs

(piscina;), in which the water might deposit any sediment that it

contained. Vitruvius has given rules for the laying down of pipes,

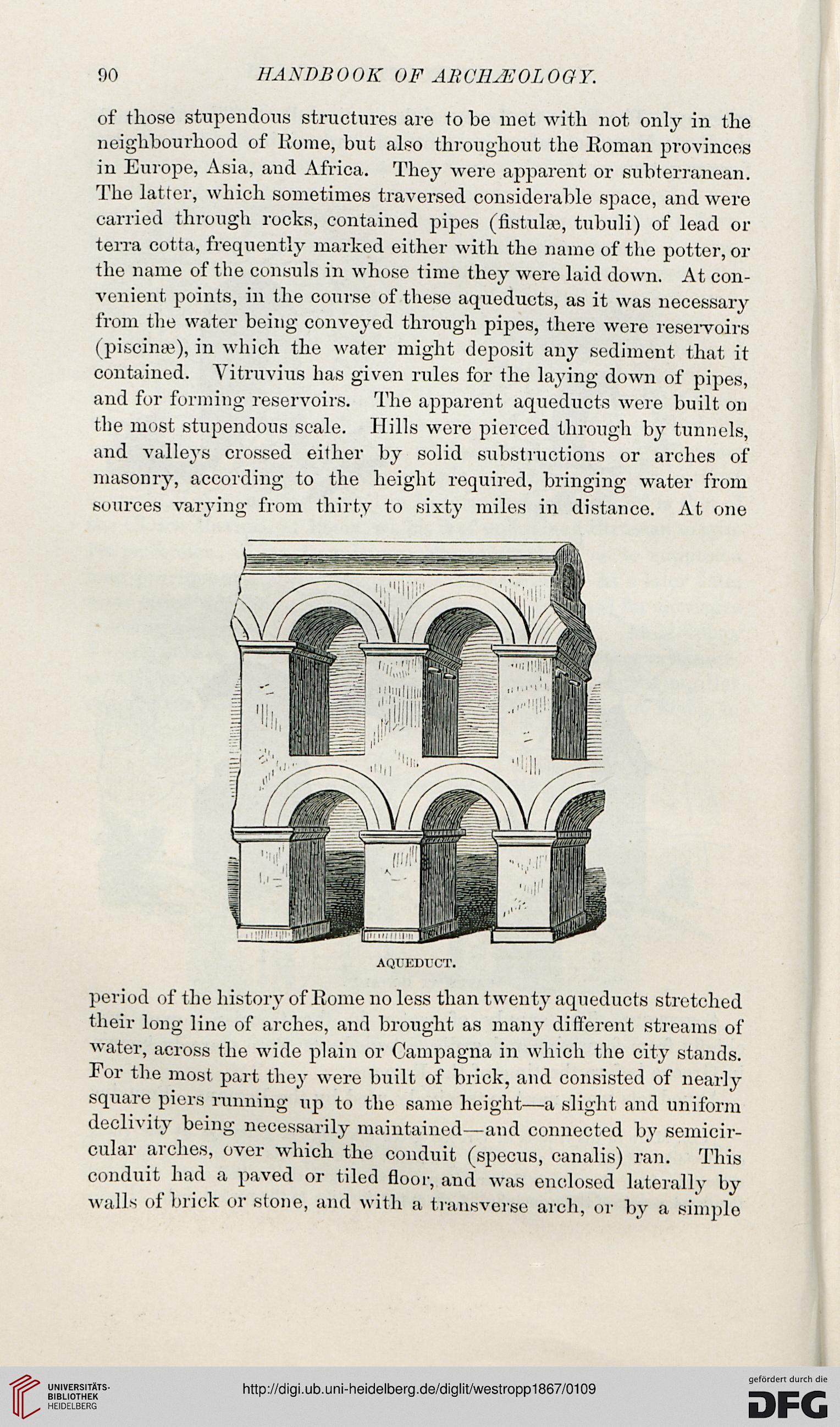

and for forming reservoirs. The apparent aqueducts were built on

the most stupendous scale. Hills were pierced through by tunnels,

and valleys crossed either by solid substructions or arches of

masonry, according to the height required, bringing water from

sources varying from thirty to sixty miles in distance. At one

AQl'EDUCT.

period of the history of Rome no less than twenty aqueducts stretched

their long line of arches, and brought as many different streams of

water, across the wide plain or Campagna in which the city stands.

For the most part they were built of brick, and consisted of nearly

square piers running up to the same height—a slight and uniform

declivity being necessarily maintained—and connected by semicii'-

cular arches, over which the conduit (specus, canalis) ran. This

conduit had a paved or tiled floor, and was enclosed laterally by

walls of brick or stone, and with a transverse arch, or by a simple

HANDBOOK OF ABCEJEOLOGT.

of those stupendous structures are to be met with not only in the

neighbourhood of Rome, but also throughout the Roman provinces

in Europe, Asia, and Africa. They were apparent or subterranean.

The latter, which sometimes traversed considerable space, and were

carried through rocks, contained pipes (fistula;, tubuli) of lead or

terra cotta, frequently marked either with the name of the potter, or

the name of the consuls in whose time they were laid down. At con-

venient points, in the course of these aqueducts, as it was necessary

from the water being conveyed through pipes, there were reservoirs

(piscina;), in which the water might deposit any sediment that it

contained. Vitruvius has given rules for the laying down of pipes,

and for forming reservoirs. The apparent aqueducts were built on

the most stupendous scale. Hills were pierced through by tunnels,

and valleys crossed either by solid substructions or arches of

masonry, according to the height required, bringing water from

sources varying from thirty to sixty miles in distance. At one

AQl'EDUCT.

period of the history of Rome no less than twenty aqueducts stretched

their long line of arches, and brought as many different streams of

water, across the wide plain or Campagna in which the city stands.

For the most part they were built of brick, and consisted of nearly

square piers running up to the same height—a slight and uniform

declivity being necessarily maintained—and connected by semicii'-

cular arches, over which the conduit (specus, canalis) ran. This

conduit had a paved or tiled floor, and was enclosed laterally by

walls of brick or stone, and with a transverse arch, or by a simple