6

ENGINEER AND MACHINIST’S DRAWING-BOOK.

vertical position at any extension ; but this is a doubtful

advantage, especially in compasses designed for drawing

arcs and circles, since each leg being equally removed from

the centre of motion, there must be a tendency on the

part of the one fixed, to tear away from its position.

Mr. Brunei has introduced what are called Tubular Com-

passes, in which the upper part of the legs lengthens out

like the slide of a telescope, thus giving greater extent of

radius when required. The movable legs are double,

having points at one end, and a pencil or pen at the other ;

and they move on pivots, so that the pen or pencil can be

instantly substituted for the points, or vice versa, and that

with the certainty of a perfect adjustment. The design

is very ingenious, and offers many conveniences, but the

instrument is too delicate for ordinary hands. Without

extreme care, it must soon be disarranged and rendered

useless. The Portable or Turn-in Compasses, is a con-

trivance which combines dividers, compasses with movable

legs, and bows, in a pocket instrument, folding up to a

length of not more than three inches. The upper legs are

hollow, and admit either leg of the pen and pencil bows,

which can therefore be substituted for each other. When

closed for the pocket, one leg of each bow slides into the

upper legs, and the other is turned inward towards the

head.

As a concluding remark, we recommend the draughts-

man to choose compasses in which the joint is formed by

a box-screw, that can be tightened or relaxed at pleasure.

The cheaper kinds have merely a common screw, and

these are usually too stiff when first purchased, and in-

conveniently loose after being some time in wear. A slight

turn of the box-screw, by means of the key, keeps the com-

passes in good working order, neither so stiff as to spring,

nor so loose as to render them uncertain and unsteady

in use.

Plain and Double Scales.

Simply-divided Scales.—Scales are measures and sub-

divisions of measures laid down with such accuracy, that

any drawing constructed by them, shall be in exact pro-

portion in all its details. The plain scale is a series of

measures laid down on the face of one small flat ruler, and

is thus distinguished from the sector, or double scales, in

which two similarly divided rulers move on a joint, and

open to a greater or less angle. In the construction of

scales, the subdivison must be carried to as low a denomi-

nation as is likely to be required. Thus, for a drawing of

limited extent, the primary divisions may be feet, and the

subdivisions inches ; but for one of large area, and without

small details, the primaries may be 10 feet, and the sub-

hn-k

r i i' i i 1

ttH-

-H-

!

10

5

_._1____

o

■ 7_

10

20

1—1L_i_J

i 1 i i

1 i L

-1-

-r-^==T7--=d

divisions tenths, or one foot each (Figs. 9 and 10). And

in the case of large surveys, the primaries become miles,

and the lesser divisions furlongs. Indeed the natural size

or extent of the object or area, and the surface to be

occupied by the delineation, must determine the graduation

of the scale. But passing from these general remarks, we

proceed to the plain scales contained in the Drawing Case,

and laid down on the tw.o sides of a flat ivory ruler, six

inches in length.

On one side of the Plain Scale there is usually a series

of simple scales, in which the inch is variously divided,

and the primaries subdivided into tenths and twelfths.

These may be applied to measurements as inches and

tenths, or twelfths; or as feet and tenths, or inches,

according to the nature of the drawing. It may be re-

marked, however, that these small lines of measures are

of only limited use, and that the engineering draughts-

man must usually lay down a scale with special reference

to the work before him; and in all cases it is desirable to

have the scale of construction on the margin of the draw-

ing itself, since the paper contracts or expands with every

atmospheric change, and the measurements will therefore

not agree at all times with a detached scale; and, moreover,

a drawing laid down from such detached scale, of wood or

ivory, will not be uniform throughout, for on a damp day the

measurements will be too short, and on a dry day too long.

Mr. Holtzapffel has sought to remedy this inconvenience,

by the introduction of paper scales; but all kinds of paper

do not contract and expand equally, and the error is

therefore only partially corrected by his ingenious substi-

tution of one material for another.

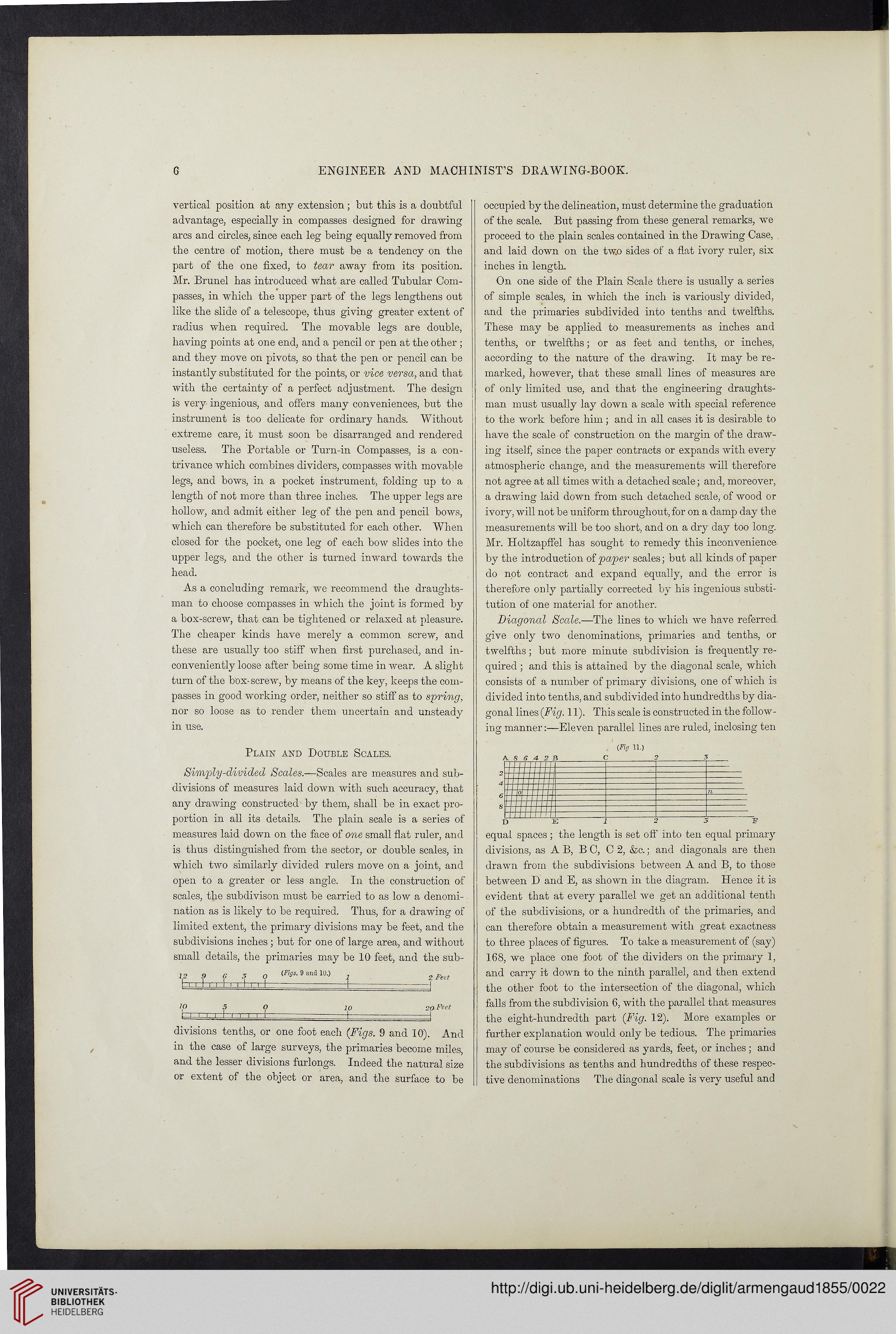

Diagonal Sccde.—The lines to which we have referred,

give only two denominations, primaries and tenths, or

twelfths; but more minute subdivision is frequently re-

quired ; and this is attained by the diagonal scale, which

consists of a number of primary divisions, one of which is

divided into tenths, and subdivided into hundredths by dia-

gonal lines (Fig. 11). This scale is constructed in the foliow-

iug manner:—Eleven parallel lines are ruled, inclosing ten

(Fig 11.)

A. S S 4 2 B C

equal spaces; the length is set off into ten equal primary

divisions, as A B, B C, C 2, &c.; and diagonals are then

drawn from the subdivisions between A and B, to those

between D and E, as shown in the diagram. Hence it is

evident that at every parallel we get an additional tenth

of the subdivisions, or a hundredth of the primaries, and

can therefore obtain a measurement with great exactness

to three places of figures. To take a measurement of (say)

168, we place one foot of the dividers on the primary 1,

and carry it down to the ninth parallel, and then extend

the other foot to the intersection of the diagonal, which

falls from the subdivision 6, with the parallel that measures

the eight-hundredth part (Fig. 12). More examples or

further explanation would only be tedious. The primaries

may of course be considered as yards, feet, or inches; and

the subdivisions as tenths and hundredths of these respec-

tive denominations The diagonal scale is very useful and

ENGINEER AND MACHINIST’S DRAWING-BOOK.

vertical position at any extension ; but this is a doubtful

advantage, especially in compasses designed for drawing

arcs and circles, since each leg being equally removed from

the centre of motion, there must be a tendency on the

part of the one fixed, to tear away from its position.

Mr. Brunei has introduced what are called Tubular Com-

passes, in which the upper part of the legs lengthens out

like the slide of a telescope, thus giving greater extent of

radius when required. The movable legs are double,

having points at one end, and a pencil or pen at the other ;

and they move on pivots, so that the pen or pencil can be

instantly substituted for the points, or vice versa, and that

with the certainty of a perfect adjustment. The design

is very ingenious, and offers many conveniences, but the

instrument is too delicate for ordinary hands. Without

extreme care, it must soon be disarranged and rendered

useless. The Portable or Turn-in Compasses, is a con-

trivance which combines dividers, compasses with movable

legs, and bows, in a pocket instrument, folding up to a

length of not more than three inches. The upper legs are

hollow, and admit either leg of the pen and pencil bows,

which can therefore be substituted for each other. When

closed for the pocket, one leg of each bow slides into the

upper legs, and the other is turned inward towards the

head.

As a concluding remark, we recommend the draughts-

man to choose compasses in which the joint is formed by

a box-screw, that can be tightened or relaxed at pleasure.

The cheaper kinds have merely a common screw, and

these are usually too stiff when first purchased, and in-

conveniently loose after being some time in wear. A slight

turn of the box-screw, by means of the key, keeps the com-

passes in good working order, neither so stiff as to spring,

nor so loose as to render them uncertain and unsteady

in use.

Plain and Double Scales.

Simply-divided Scales.—Scales are measures and sub-

divisions of measures laid down with such accuracy, that

any drawing constructed by them, shall be in exact pro-

portion in all its details. The plain scale is a series of

measures laid down on the face of one small flat ruler, and

is thus distinguished from the sector, or double scales, in

which two similarly divided rulers move on a joint, and

open to a greater or less angle. In the construction of

scales, the subdivison must be carried to as low a denomi-

nation as is likely to be required. Thus, for a drawing of

limited extent, the primary divisions may be feet, and the

subdivisions inches ; but for one of large area, and without

small details, the primaries may be 10 feet, and the sub-

hn-k

r i i' i i 1

ttH-

-H-

!

10

5

_._1____

o

■ 7_

10

20

1—1L_i_J

i 1 i i

1 i L

-1-

-r-^==T7--=d

divisions tenths, or one foot each (Figs. 9 and 10). And

in the case of large surveys, the primaries become miles,

and the lesser divisions furlongs. Indeed the natural size

or extent of the object or area, and the surface to be

occupied by the delineation, must determine the graduation

of the scale. But passing from these general remarks, we

proceed to the plain scales contained in the Drawing Case,

and laid down on the tw.o sides of a flat ivory ruler, six

inches in length.

On one side of the Plain Scale there is usually a series

of simple scales, in which the inch is variously divided,

and the primaries subdivided into tenths and twelfths.

These may be applied to measurements as inches and

tenths, or twelfths; or as feet and tenths, or inches,

according to the nature of the drawing. It may be re-

marked, however, that these small lines of measures are

of only limited use, and that the engineering draughts-

man must usually lay down a scale with special reference

to the work before him; and in all cases it is desirable to

have the scale of construction on the margin of the draw-

ing itself, since the paper contracts or expands with every

atmospheric change, and the measurements will therefore

not agree at all times with a detached scale; and, moreover,

a drawing laid down from such detached scale, of wood or

ivory, will not be uniform throughout, for on a damp day the

measurements will be too short, and on a dry day too long.

Mr. Holtzapffel has sought to remedy this inconvenience,

by the introduction of paper scales; but all kinds of paper

do not contract and expand equally, and the error is

therefore only partially corrected by his ingenious substi-

tution of one material for another.

Diagonal Sccde.—The lines to which we have referred,

give only two denominations, primaries and tenths, or

twelfths; but more minute subdivision is frequently re-

quired ; and this is attained by the diagonal scale, which

consists of a number of primary divisions, one of which is

divided into tenths, and subdivided into hundredths by dia-

gonal lines (Fig. 11). This scale is constructed in the foliow-

iug manner:—Eleven parallel lines are ruled, inclosing ten

(Fig 11.)

A. S S 4 2 B C

equal spaces; the length is set off into ten equal primary

divisions, as A B, B C, C 2, &c.; and diagonals are then

drawn from the subdivisions between A and B, to those

between D and E, as shown in the diagram. Hence it is

evident that at every parallel we get an additional tenth

of the subdivisions, or a hundredth of the primaries, and

can therefore obtain a measurement with great exactness

to three places of figures. To take a measurement of (say)

168, we place one foot of the dividers on the primary 1,

and carry it down to the ninth parallel, and then extend

the other foot to the intersection of the diagonal, which

falls from the subdivision 6, with the parallel that measures

the eight-hundredth part (Fig. 12). More examples or

further explanation would only be tedious. The primaries

may of course be considered as yards, feet, or inches; and

the subdivisions as tenths and hundredths of these respec-

tive denominations The diagonal scale is very useful and