10

ENGINEER AND MACHINIST’S DRAWING-ROOK.

(that is, without the circumference), the inscribed figure

must first be drawn ; then rule lines parallel to the sides

of the inscribed figure, so as just to touch the circum-

ference, and their intersections will define the polygon

required.

As we propose to explain the construction and use of

every line on the sector, which is often little more to the

young draughtsman than a puzzling hieroglyphic, we

must anticipate the definitions with which the Second

Part will open, so far as to define the geometrical cha-

racter and relation of the several lines to which the sec-

toral scales refer. We have discussed the chord, which is

simply a straight line connecting the extremities of any

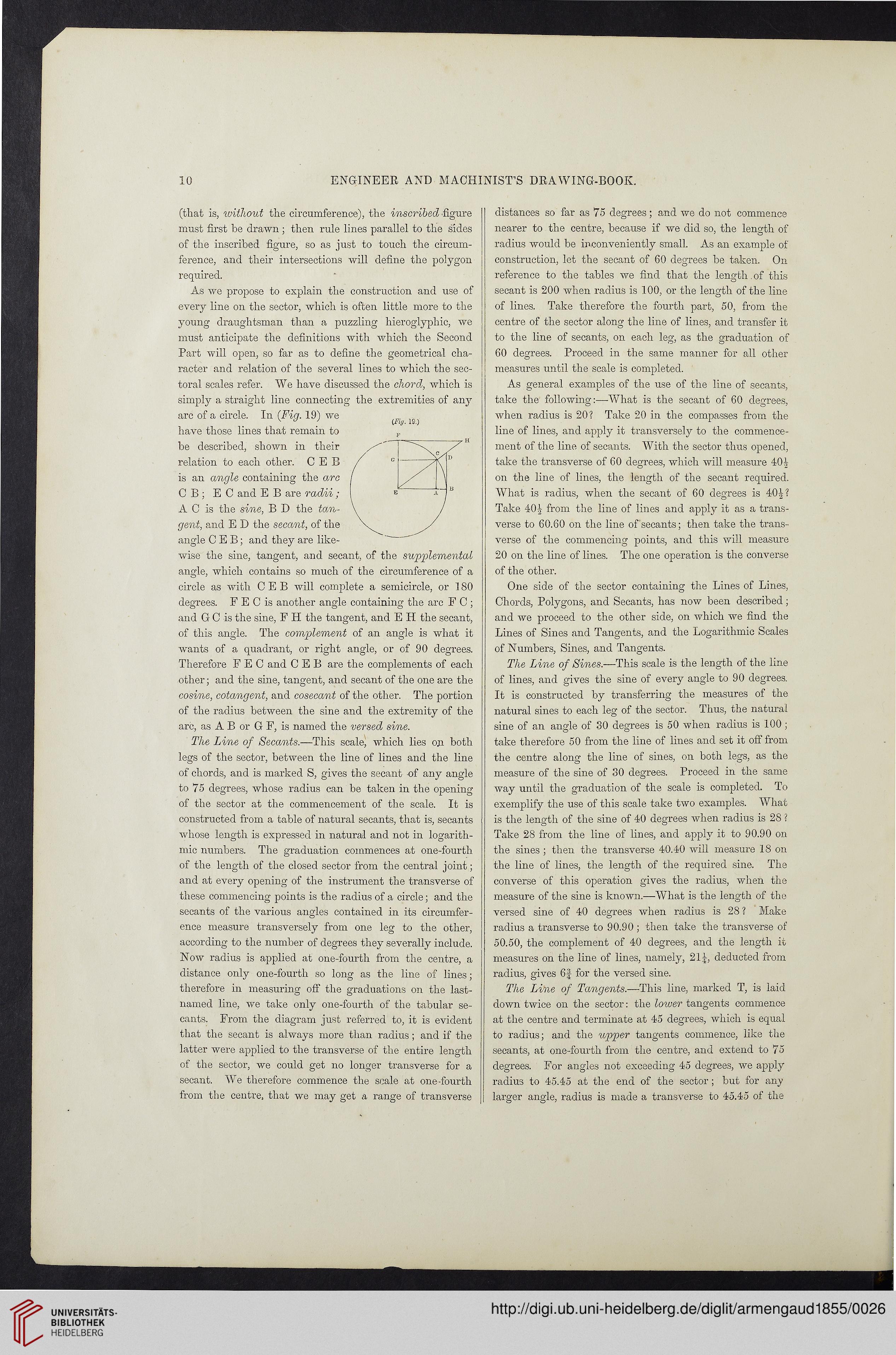

arc of a circle. In {Fig. 19) we

have those lines that remain to

be described, shown in their

relation to each other. CEB

is an angle containing the arc

C B ; EC and E B are radii ;

A C is the sine, B D the tan-

gent, and E D the secant, of the

angle CEB; and they are like-

wise the sine, tangent, and secant, of the supplemental

angle, which contains so much of the circumference of a

circle as with CEB will complete a semicircle, or 180

degrees. F E C is another angle containing the arc F C ;

and G C is the sine, F H the tangent, and E H the secant,

of this angle. The complement of an angle is what it

wants of a quadrant, or right angle, or of 90 degrees.

Therefore F E C and CEB are the complements of each

other; and the sine, tangent, and secant of the one are the

cosine, cotangent, and cosecant of the other. The portion

of the radius between the sine and the extremity of the

arc, as A B or G F, is named the versed sine.

The Line of Secants.—This scale, which lies on both

legs of the sector, between the line of lines and the line

of chords, and is marked S, gives the secant of any angle

to 75 degrees, whose radius can be taken in the opening

of the sector at the commencement of the scale. It is

constructed from a table of natural secants, that is, secants

whose length is expressed in natural and not in logarith-

mic numbers. The graduation commences at one-fourth

of the length of the closed sector from the central joint;

and at every opening of the instrument the transverse of

these commencing points is the radius of a circle; and the

secants of the various angles contained in its circumfer-

ence measure transversely from one leg to the other,

according to the number of degrees they severally include.

Now radius is applied at one-fourth from the centre, a

distance only one-fourth so long as the line of lines;

therefore in measuring off the graduations on the last-

named line, we take only one-fourth of the tabular se-

cants. From the diagram just referred to, it is evident

that the secant is always more than radius ; and if the

latter were applied to the transverse of the entire length

of the sector, we could get no longer transverse for a

secant. We therefore commence the scale at one-fourth

from the centre, that we may get a range of transverse

distances so far as 75 degrees; and we do not commence

nearer to the centre, because if we did so, the length of

radius would be inconveniently small. As an example of

construction, let the secant of 60 degrees be taken. On

reference to the tables we find that the length. of this

secant is 200 when radius is 100, or the length of the line

of lines. Take therefore the fourth part, 50, from the

centre of the sector along the line of lines, and transfer it

to the line of secants, on each leg, as the graduation of

60 degrees. Proceed in the same manner for all other

measures until the scale is completed.

As general examples of the use of the line of secants,

take the following:—What is the secant of 60 degrees,

when radius is 20? Take 20 in the compasses from the

line of lines, and apply it transversely to the commence-

ment of the line of secants. With the sector thus opened,

take the transverse of 60 degrees, which will measure 401

on the line of lines, the length of the secant required.

What is radius, when the secant of 60 degrees is 40 f?

Take 40f from the line of lines and apply it as a trans-

verse to 60.60 on the line of'secants; then take the trans-

verse of the commencing points, and this will measure

20 on the line of lines. The one operation is the converse

of the other.

One side of the sector containing the Lines of Lines,

Chords, Polygons, and Secants, has now been described;

and we proceed to the other side, on which we find the

Lines of Sines and Tangents, and the Logarithmic Scales

of Numbers, Sines, and Tangents.

The Line of Sines.—This scale is the length of the line

of lines, and gives the sine of every angle to 90 degrees.

It is constructed by transferring the measures of the

natural sines to each leg of the sector. Thus, the natural

sine of an angle of 30 degrees is 50 when radius is 100 ;

take therefore 50 from the line of lines and set it off from

the centre along the line of sines, on both legs, as the

measure of the sine of 30 degrees. Proceed in the same

way until the graduation of the scale is completed. To

exemplify the use of this scale take two examples. What

is the length of the sine of 40 degrees when radius is 28 ?

Take 28 from the line of lines, and apply it to 90.90 on

the sines ; then the transverse 40.40 will measure 18 on

the line of lines, the length of the required sine. The

converse of this operation gives the radius, when the

measure of the sine is known.—What is the length of the

versed sine of 40 degrees when radius is 28 ? Make

radius a transverse to 90.90 ; then take the transverse of

50.50, the complement of 40 degrees, and the length it

measures on the line of lines, namely, 21 f, deducted from

radius, gives 6| for the versed sine.

The Line of Tangents.—This line, marked T, is laid

down twice on the sector: the lower tangents commence

at the centre and terminate at 45 degrees, which is equal

to radius; and the upper tangents commence, like the

secants, at one-fourth from the centre, and extend to 75

degrees. For angles not exceeding 45 degrees, we apply

radius to 45.45 at the end of the sector ; but for any

larger angle, radius is made a transverse to 45.45 of the

(Fig. IS.)

F

ENGINEER AND MACHINIST’S DRAWING-ROOK.

(that is, without the circumference), the inscribed figure

must first be drawn ; then rule lines parallel to the sides

of the inscribed figure, so as just to touch the circum-

ference, and their intersections will define the polygon

required.

As we propose to explain the construction and use of

every line on the sector, which is often little more to the

young draughtsman than a puzzling hieroglyphic, we

must anticipate the definitions with which the Second

Part will open, so far as to define the geometrical cha-

racter and relation of the several lines to which the sec-

toral scales refer. We have discussed the chord, which is

simply a straight line connecting the extremities of any

arc of a circle. In {Fig. 19) we

have those lines that remain to

be described, shown in their

relation to each other. CEB

is an angle containing the arc

C B ; EC and E B are radii ;

A C is the sine, B D the tan-

gent, and E D the secant, of the

angle CEB; and they are like-

wise the sine, tangent, and secant, of the supplemental

angle, which contains so much of the circumference of a

circle as with CEB will complete a semicircle, or 180

degrees. F E C is another angle containing the arc F C ;

and G C is the sine, F H the tangent, and E H the secant,

of this angle. The complement of an angle is what it

wants of a quadrant, or right angle, or of 90 degrees.

Therefore F E C and CEB are the complements of each

other; and the sine, tangent, and secant of the one are the

cosine, cotangent, and cosecant of the other. The portion

of the radius between the sine and the extremity of the

arc, as A B or G F, is named the versed sine.

The Line of Secants.—This scale, which lies on both

legs of the sector, between the line of lines and the line

of chords, and is marked S, gives the secant of any angle

to 75 degrees, whose radius can be taken in the opening

of the sector at the commencement of the scale. It is

constructed from a table of natural secants, that is, secants

whose length is expressed in natural and not in logarith-

mic numbers. The graduation commences at one-fourth

of the length of the closed sector from the central joint;

and at every opening of the instrument the transverse of

these commencing points is the radius of a circle; and the

secants of the various angles contained in its circumfer-

ence measure transversely from one leg to the other,

according to the number of degrees they severally include.

Now radius is applied at one-fourth from the centre, a

distance only one-fourth so long as the line of lines;

therefore in measuring off the graduations on the last-

named line, we take only one-fourth of the tabular se-

cants. From the diagram just referred to, it is evident

that the secant is always more than radius ; and if the

latter were applied to the transverse of the entire length

of the sector, we could get no longer transverse for a

secant. We therefore commence the scale at one-fourth

from the centre, that we may get a range of transverse

distances so far as 75 degrees; and we do not commence

nearer to the centre, because if we did so, the length of

radius would be inconveniently small. As an example of

construction, let the secant of 60 degrees be taken. On

reference to the tables we find that the length. of this

secant is 200 when radius is 100, or the length of the line

of lines. Take therefore the fourth part, 50, from the

centre of the sector along the line of lines, and transfer it

to the line of secants, on each leg, as the graduation of

60 degrees. Proceed in the same manner for all other

measures until the scale is completed.

As general examples of the use of the line of secants,

take the following:—What is the secant of 60 degrees,

when radius is 20? Take 20 in the compasses from the

line of lines, and apply it transversely to the commence-

ment of the line of secants. With the sector thus opened,

take the transverse of 60 degrees, which will measure 401

on the line of lines, the length of the secant required.

What is radius, when the secant of 60 degrees is 40 f?

Take 40f from the line of lines and apply it as a trans-

verse to 60.60 on the line of'secants; then take the trans-

verse of the commencing points, and this will measure

20 on the line of lines. The one operation is the converse

of the other.

One side of the sector containing the Lines of Lines,

Chords, Polygons, and Secants, has now been described;

and we proceed to the other side, on which we find the

Lines of Sines and Tangents, and the Logarithmic Scales

of Numbers, Sines, and Tangents.

The Line of Sines.—This scale is the length of the line

of lines, and gives the sine of every angle to 90 degrees.

It is constructed by transferring the measures of the

natural sines to each leg of the sector. Thus, the natural

sine of an angle of 30 degrees is 50 when radius is 100 ;

take therefore 50 from the line of lines and set it off from

the centre along the line of sines, on both legs, as the

measure of the sine of 30 degrees. Proceed in the same

way until the graduation of the scale is completed. To

exemplify the use of this scale take two examples. What

is the length of the sine of 40 degrees when radius is 28 ?

Take 28 from the line of lines, and apply it to 90.90 on

the sines ; then the transverse 40.40 will measure 18 on

the line of lines, the length of the required sine. The

converse of this operation gives the radius, when the

measure of the sine is known.—What is the length of the

versed sine of 40 degrees when radius is 28 ? Make

radius a transverse to 90.90 ; then take the transverse of

50.50, the complement of 40 degrees, and the length it

measures on the line of lines, namely, 21 f, deducted from

radius, gives 6| for the versed sine.

The Line of Tangents.—This line, marked T, is laid

down twice on the sector: the lower tangents commence

at the centre and terminate at 45 degrees, which is equal

to radius; and the upper tangents commence, like the

secants, at one-fourth from the centre, and extend to 75

degrees. For angles not exceeding 45 degrees, we apply

radius to 45.45 at the end of the sector ; but for any

larger angle, radius is made a transverse to 45.45 of the

(Fig. IS.)

F